Forget the Amazon Fires. State-Sanctioned Deforestation Is the Bigger Problem.

Environmental commons like the Amazon rain forest are vulnerable to shifts in the fickle winds of politics.

"Amazon burning at record rate" and variations of the same headline have run on CNN, The Hill, Time, UPI, and The Daily Beast during the last week. Reacting to the dire news reports, French President Emmanuel Macron declared, "The Amazon forest is a subject for the whole planet." He added, "We cannot allow you to destroy everything."

At the urging of Macron, the G7 countries meeting in Biarritz, France, offered a $20 million aid package to help fight the fires. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro initially rejected the aid, but now says that his country may accept it if Macron withdraws his "insults."

Celebrities also rushed to help. Actor Leonardo DiCaprio's Earth Alliance pledged $5 million to aid various Brazilian nonprofits associated with indigenous peoples in protecting the Amazon rain forest. Good for him. Helping indigenous folks to assert and protect their property rights is certainly a worthy goal.

So why are there so many fires burning now in the Amazon region? Chiefly, because local farmers and ranchers have set them to control pests and weeds and to encourage new growth, according to University of Maryland geographer Matthew Hansen. The increase in fires every August to October coincides with the season when farmers begin planting soybean and corn.

"The first thing is that they're not wildfires. Almost all of the fires have been set, so they're anthropogenic in origin. A minority are actually in the rainforest," explains Hansen, head of a NASA satellite project that tracks changes in earth's vegetation and forests in an interview in Maryland Today. "The vast majority look like maintenance fires set on already cleared land, which farmers might be burning to reduce vegetation cover in expanding land use, pastures in most cases."

Hansen adds, "Overall, fires inside standing rainforest are similar to recent years, the difference being that most have occurred in the last few weeks, leading to a concentrated spike in emissions."

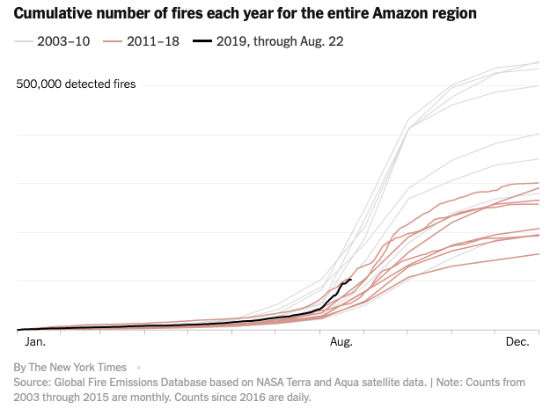

Interestingly, the Global Fire Emissions Database, citing a satellite record that begins in 2012, "confirm[s] that the 2019 fire season has the highest fire count since 2012 across the Legal Amazon." The Legal Amazon consists of the nine states that essentially encompass Brazil's rain forests. According to records beginning in 1998, from Brazil's National Space Research Institute, the number of active fires (33,405) detected by satellites for the month of August are indeed more than double what they were in the previous year (15,001). On the other hand, the number of current fires is way down from earlier years. Since 1998, fires exceeded the current number in eight prior years, with 73,683 fires in the peak year of 2005.

The bottom line is that the current fires are not a significant threat to the Amazon rain forest, but state-sanctioned deforestation is.

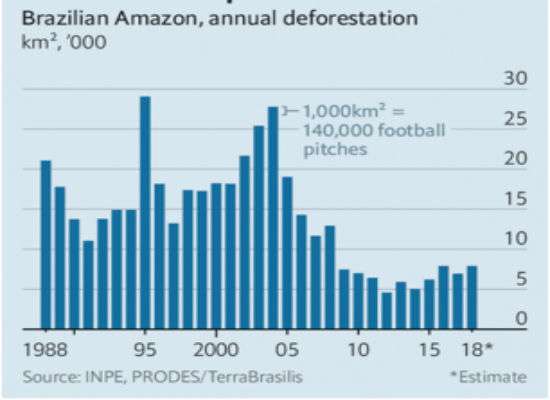

Although some fires set by farmers do get out of hand and burn down nearby rain forests, the much bigger problem has been deforestation. The most recent peak year of 2004 saw the loss of 27,772 square kilometers (10,722 square miles) of rain forest. That's an area about the size of Maryland. As always, environmental commons like the Amazon rain forest are vulnerable to shifts in the fickle winds of politics.

For example, under the left-leaning administration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2003, the deforestation trends began to decline, reaching a record low in 2012 of 4,571 square kilometers (1,765 square miles). That's about the size of Delaware. During that period, the Brazilian government expanded protected areas and, importantly, stepped up enforcement against illegal deforestation.

However, Brazil revised its Forest Code in 2012 such that it included an amnesty program for illegal deforestation on "small properties" that occurred before 2008. It also reduced forest restoration requirements. Some landowners near the rain forest evidently interpreted the amnesty as a green light for further land clearing. Consequently, under the administrations of Dilma Rousseff and Michel Temer, deforestation rates began trending somewhat upward, rising to 7,000 square kilometers last year (3,050 square miles).

As I noted earlier, a 2012 study on forest transitions found, after parsing data from 52 developing countries between 1972 and 2003, that deforestation increases until average income levels reach about $3,100 per capita. Similarly, a 2016 study by French researchers focusing on Amazonian deforestation calculated that "the point when deforestation starts to decrease, corresponds to an income around 4,600 in [2005 U.S. dollars]." That's about $6,000 currently.

As it happens, Brazilian per capita incomes reached $3,600 per capita in 2004, and more than $7,000 per capita in 2007, coinciding with the beginning of downward trending deforestation rates.

However, a 2019 article by Colorado State University economist Edward Barbier specifically analyzed how institutions such as the rule of law and greater voice affect deforestation and reforestation trends in tropical countries. Not too surprisingly, the strengthening of the rule of law accelerates the speed with which an economy transitions from deforestation to forest recovery.

Somewhat paradoxically, Barbier finds that better voice and accountability diminishes rather than increases the likelihood of a forest transition in tropical countries. He observes that large state-funded settlement projects have been replaced by decentralized decision-making by farmers, land speculators, agri-business enterprises, and ranchers. These local private enterprises join together into an effective lobby.

"Evidence for some developing countries has shown that such lobbying efforts may enhance private agents' legal claims to forested land, encouraging land-use policies more favorable to their interests, and thus the profitability of their land clearing activities," suggests Barbier. "The result may well be further postponement of the transition to forest recovery in many tropical developing countries." According to media reports, this dynamic is happening in the Bolsonaro administration.

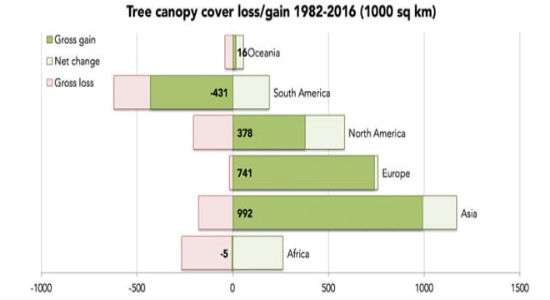

Sadly, crony capitalism can delay the forest transition, but in the long run, rising incomes and urbanization will strengthen the rule of law and deforestation of the Amazon rain forest will likely reverse, as it has already in most of the rest of the world.

Show Comments (51)