Joe Biden Concedes the 'Assault Weapon' Ban He Wants To Revive Had No Impact on the Lethality of Legal Guns

The presidential contender nevertheless insists the law reduced mass shooting deaths.

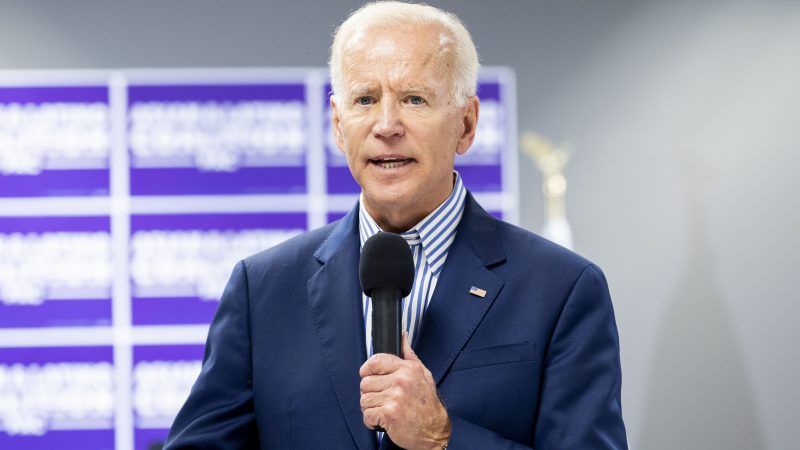

Joe Biden, who just a few years ago was still bragging about "the 1994 Biden Crime Bill," has since had second thoughts about aspects of that law, including its expansion of mandatory minimums and crimes subject to the death penalty. But the former Democratic senator and vice president, who is the leading contender for his party's 2020 presidential nomination, is still proud of the ban on "assault weapons" that was also included in that law, and he tries to explain why in a New York Times op-ed piece published yesterday.

Even while conceding that the "assault weapon" ban left lots of equally lethal firearms on the market, Biden argues that it made mass shootings less common. "From 1994 to 2004, the years when assault weapons and high-capacity magazines were banned, there were fewer mass shootings," he writes, citing a study reported in The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery last January. But that is not what the researchers, led by New York University epidemiologist Charles DiMaggio, actually found.

Drawing on three databases of mass shootings (maintained by Mother Jones, the Los Angeles Times, and researchers at Stanford University), DiMaggio focused on shootings that killed at least four people, the definition used by the FBI. "In a linear regression model controlling for yearly trend, the federal ban period was associated with a statistically significant 9 fewer mass shooting-related deaths per 10,000 firearm homicides," they reported. "Mass-shooting fatalities were 70% less likely to occur during the federal ban period."

The study, in other words, looked not at the number of mass shootings, as Biden claims, but the number of mass-shooting deaths as a share of all firearm homicides. The difference in total fatalities during the period when the ban was in effect amounted to 15 fewer deaths over a decade, or 1.5 a year on average, including mass shootings that did not involve weapons covered by the ban. That's based on a comparison of deaths from 1981 through 1993 to deaths from 1994 through 2004, the year the ban expired. Leaving aside the fact that the pre-ban period is two years longer than the ban period, "the drop of 15 mass shooting deaths from before the ban to during it is a slender difference on which to base firm conclusions," as Jon Greenberg notes in a recent Politifact analysis,

DiMaggio et al. concede that "no observational epidemiologic study can answer the question whether the 1994 US federal assault ban was causally related to preventing mass-shooting homicides." Furthermore, DiMaggio told Greenberg it's not clear that the rate of mass shooting deaths (per 100,000 Americans) fell during the ban period. "There is some evidence they actually declined—or at least didn't continue to increase during the period of the ban," he said.

Greenberg also quoted RAND economist Rosanna Stewart, who wrote a 2018 analysis concluding that the results of two earlier studies looking at the impact of the "assault weapon" ban on mass shootings were "inconclusive." Stewart is still unconvinced. "I don't think [DiMaggio's] methods are well-suited for determining the causal impact of the assault weapons ban," she told Greenberg.

Mass shootings are very rare events; between 1981 and 2017, the period covered by DiMaggio et al.'s study, there were just 44, or an average of about one a year, that met their criteria. Furthermore, the numbers related to these crimes are highly volatile; in 2017, for example, a single incident, the massacre in Las Vegas, accounted for 60 percent of deaths in mass shootings that killed four or more people. That volatility makes correlations with a single policy difficult to identify and interpret.

The causal mechanism imagined by Biden is even harder to figure out. He describes "assault weapons" as "military-style firearms designed to fire rapidly." But they do not fire any faster than any other semi-automatic. He also says "shootings committed with assault weapons kill more people than shootings with other types of guns." While it's true that "assault weapons" figure disproportionately in the deadliest shootings, it does not follow that eliminating them would make shootings less deadly.

Most mass shootings, including three of the 10 deadliest since 1949, do not involve "assault weapons." Going further down the list of deadliest shootings, the next 17 (some of which are tied in their rank) include 11 that involved only handguns and/or shotguns. If all the firearms in the arbitrary "assault weapon" category disappeared overnight, there would still be plenty of equally deadly alternatives.

Biden actually concedes this point, saying he favors a modified "assault weapon" ban that would "stop gun manufacturers from circumventing the law by making minor modifications to their products—modifications that leave them just as deadly." Biden thus admits that the 1994 ban, the one he credits with reducing the frequency of mass shootings and the deaths caused by them, drew distinctions that had no practical significance, since the guns that remained legal were "just as deadly."

Biden is right. Under the 1994 ban, removing "military-style" features such as folding stocks, flash suppressors, or bayonet mounts transformed forbidden "assault weapons" into legal firearms, even though the compliant models fired the same ammunition at the same rate with the same muzzle velocity as the ones targeted by the law. But that is also true of the new, supposedly improved "assault weapon" ban sponsored by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D–Calif.), who wrote the 1994 ban. Feinstein has fiddled with the list of military-style features (omitting bayonet mounts while adding barrel shrouds, for instance), and any one of them would now be sufficient to make a rifle illegal, whereas two were required under the 1994 law. But the problem identified by Biden remains: Removing these forbidden features results in a gun that is "just as deadly."

It's not clear how Biden thinks he can solve that problem, since focusing on functionally significant features such as rate of fire, ammunition, and muzzle velocity or muzzle energy would result in a ban that covers many commonly owned firearms that were not heretofore considered "assault weapons" (and are in fact specifically exempted by Feinstein's new bill). Nor is it clear what Biden plans to do about the 16 million or so "assault weapons" that are already in circulation. He mentions "a buyback program to get as many assault weapons off our streets as possible as quickly as possible." But unless that "buyback" is mandatory (i.e., a form of compensated confiscation), it will have no impact on people who like their guns and want to keep them. And judging from past experience in the United States and other countries, a ban that includes current possession would be honored mostly in the breach.

Biden cites a 2019 poll, conducted immediately after the mass shootings in El Paso and Dayton, that found 70 percent of voters, including 54 percent of Republicans, either "strongly" or "somewhat" supported "banning assault-style weapons." But since 1996, according to Gallup, support for a ban on "semi-automatic guns known as assault rifles" has ebbed and flowed, falling from a high of 59 percent in 2000 to a low of 36 percent in 2016 before rebounding to 48 percent in 2017 and falling to 40 percent last October. Data from the Reason-Rupe Public Opinion Survey (sponsored by the Reason Foundation, which publishes this website) indicate that support for such legislation is especially high among people who don't understand what it would do. While Biden is trying hard to perpetuate such confusion, his own arguments unintentionally provide some clarity.

[This post has been revised to correct the number of mass shootings that killed four or more people during the period covered by DiMaggio et al.'s study.]

Show Comments (121)