The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

The Affordable Care Act Imposes A Mandate. Not a Choice.

The Structure of NFIB v. Sebelius: Parts III.A, III.B, III.C, and III.D

On July 9, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral argument in Texas v. United States. The three members on the panel were Judges Jennifer Walker Elrod, Kurt D. Engelhardt, and Carolyn Dineen King. You can listen here.

In my first post, I considered the arguments presented concerning standing. In this post, I will focus on the arguments presented concerning whether the individual mandate is constitutional.

California (represented by Samuel Siegel) and the House of Representatives (represented by Douglas Letter) did not contend that the ACA's individual mandate could be supported by Congress's powers under the Commerce and Necessary and Proper Clauses. Nor could they. That result was foreclosed by NFIB. Judge Elrod's question (at 13:36) raised this point:

"Do you agree that we are not at liberty to uphold this [mandate] based on the commerce or necessary and proper clause, given that there are five votes on the Court against those propositions?"

She's right. Five Justices in NFIB expressly rejected that position.

Rather, the intervenors argued that the ACA does not impose a requirement to buy insurance; to the contrary, the law gave covered individuals a choice between purchasing insurance and paying a modest, non-coercive tax. In other words, it is irrelevant whether Congress has the power to enact a mandate to purchase insurance, because Congress did not enact such a mandate. (Professor Marty Lederman summarizes this position in a post, aptly titled "There is no 'mandate.'") Therefore, it is completely irrelevant what Congress did with the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The "choice" architecture has remained constant. Before 2018, people had a choice: buy insurance or pay a tax of approximately $700. After 2018, the alternate choice became paying a tax of $0.

Douglas Letter articulated this position during the oral arguments:

Letter: The Supreme Court majority [in NFIB] said there is a choice. You either shall maintain insurance or you shall pay this tax penalty. [Through the 2017 TCJA,] Congress has now said, we don't want there to be any tax penalty. We want the American people to continue having a choice.

Indeed, Letter argued that this reading was the only permissible reading of NFIB:

Letter: With the proper respect here, you must rule this way because the Supreme court told us in NFIB what the statute means and in 2017 Congress said what it meant in the text and we know.

His reading of NFIB is a common one. Indeed, I have encountered it numerous times over the past seven years while teaching and writing about NFIB. Respectfully, it is an incorrect reading. Chief Justice Roberts only accepted the "choice" argument as part of the saving construction in Part III.C of his controlling opinion. However, that portion of his opinion is no longer controlling because Section 5000A can no longer be reasonably read as imposing a tax. Why? The penalty, which was reduced to $0, now raises no revenue. Part III.A, which held that the "most natural" reading of Section 5000A--imposing an unconstitutional command to buy insurance--is now the controlling opinion.

To understand why Part III.C is no longer controlling, and why the choice architecture has crumbled, we need to take a stroll down memory lane. This post will quote at some length from my 2013 book, Unprecedented. I do so to demonstrate that the injury-in-fact debate in Texas is not new. It was resolved seven years ago.

I agree with Chief Justice Roberts that Section 5000A "reads more naturally as a command to buy insurance than [offering people a choice to pay] . . . a tax." As a threshold matter, the notion that Section 5000A did not impose a mandate, but merely offered people a "choice" was manufactured at some point after the ACA was enacted. This argument was not made, publicly at least, while the law was being debated in 2009 and 2010.

During oral arguments, Judge Engeldhardt posed this question to Samuel Siegel, the lawyer for California (at 19:36):

Judge Engelhardt: Where are the statements from those who voted in 2010 saying, no worries, the individual mandate isn't really a mandate? Even though it says shall, we are voting on it today, and citizens, this is an option, you can pay a tax, or you can buy the insurance… Where are the statements from 2010, saying don't worry about the individual mandate, it's actually not something that requires you to buy insurance.

California: I don't know where those statements might be.

While writing Unprecedented, I searched the legislative history of the ACA to find support for the contention that Section 5000A imposed a "choice," rather than a mandate. I couldn't find anything. (I do not think the existence of such legislative history is necessary to resolve this question, but there are those who do find it useful.) I posed the same question to the ACA's most ardent defenders, including Obama administration officials. They could point to nothing. I remain open to being persuaded otherwise, if anyone can point to any contemporaneous discussion from before March 2010 advancing the "choice" reading of Section 5000A.

Before the Supreme Court, Solicitor General Verrilli advanced the "choice" argument. This position emerged from Judge Kavanaugh's dissent in Seven-Sky v. Holder. From p. 158 of Unprecedented:

Kavanaugh, however, made a point in passing that was not lost on the solicitor general. A statute similar to the one Congress enacted, but without the individual mandate, said the judge, would be absolutely constitutional. Kavanaugh reasoned that a "minor tweak to the current statutory language would definitively establish the law's constitutionality under the Taxing Clause (and thereby moot any need to consider the Commerce Clause)." By "eliminat[ing] the legal mandate language"—that is, by deleting a single sentence—the statute would be transformed from a command on people to purchase insurance to a mere tax on those who do not have insurance. The former was of dubious constitutionality, but the latter would be well within Congress's powers. Kavanaugh was echoing Justice Stone's whisper to Frances Perkins, "The taxing power of the Federal Government, my dear, the taxing power is sufficient for everything you want and need." Like Frances Perkins before him, the solicitor general listened carefully. Simply eliminating one sentence—the mandate—would save the law. With an assist from Judge Kavanaugh, the solicitor general advanced this very argument at the Supreme Court.

(You can read the entire chapter here.)

After Judge Kavanaugh's opinion, I noted, the government's thinking shifted (at p. 163):

The decision to take a second look at the taxing power came from the top. One reporter who covers the Supreme Court told me that Verrilli personally "insisted on pushing" it. Of course, the "obvious problem" was that the word "tax" was not in the individual mandate provision. The word used was "penalty." "Apart from that," I was told by a senior DOJ official with no irony, that the tax argument "had a lot going for it." Judge Kavanaugh's opinion convinced the Solicitor General's office that the "tax argument might be a more conservative and judicially restrained basis to act to uphold as a tax." The "nomenclature was the only serious impediment to winning." Despite this problem, the solicitor general believed that characterizing the mandate as a choice between maintaining insurance and paying a tax was not only a way of avoiding a serious constitutional question, but indeed the best reading of the law. Though it "wasn't ideal," the government determined that it "could manage" this argument. And the key to solving that problem of nomenclature fell directly on the shoulders of Donald Verrilli, with Judge Kavanaugh being credited with the "assist."

The choice argument is not new. Solicitor General Verrilli advanced this argument to the Supreme Court in 2012 (at p. 179):

Verrilli pushed back against any questions about the mandate and rejected any assertions that it was an "entirely stand-alone" requirement to buy insurance. As the government noted in its brief, citing the opinion of Judge Kavanaugh from the D.C. Circuit,"To the extent the constitutionality of [the act] depends on whether [the minimum coverage provision] creates an independent legal obligation [a mandate], the Court should construe it not to do so." In other words, in order to save the ACA, the Court should read the mandate to not be an actual mandate

Here is how Verrilli articulated the position in his brief:

Even in Judge Kavanaugh's view, however, a "minor tweak to the current statutory language would definitively establish the law's constitutionality under the Taxing Clause." Seven-Sky, 661 F.3d at 48. He suggested, for example, that Congress might retain the exactions and payment amounts as they are but eliminate the legal mandate language in Section 5000A, instead providing some- thing to the effect of: "An applicable individual without minimum essential coverage must make a payment to the IRS on his or her tax return in the amounts listed in Section 5000A(c)." Id. at 49.

In fact, no "minor tweak to the current statutory language" (Seven-Sky, 661 F.3d at 48 (Kavanaugh, dissenting)) is required because Section 5000A as currently drafted is materially indistinguishable from Judge Kavanaugh's proposed revision. Statutory provisions "must be read in * * * context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme." FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 133 (2000) (quoting Davis v. Michigan Dep't of the Treasury, 489 U.S. 803, 809 (1989)). When understood as an exercise of Congress's power over taxation and read in the context of Section 5000A as a whole, subsection (a) serves only as the predicate for tax consequences imposed by the rest of the section. It serves no other purpose in the statutory scheme. Section 5000A imposes no consequence other than a tax penalty for a taxpayer's failure to maintain minimum coverage, and it thus establishes no independently enforceable legal obligation..

Had the Supreme Court accepted Verrilli's argument, and found that "Section 5000A as currently drafted is materially indistinguishable from Judge Kavanaugh's proposed revision," then the mandate challenge in Texas v. United States would be without merit: the plaintiffs cannot challenge the individual mandate because there is no individual mandate! Letter and Lederman advanced this position. But the Court did not make such a holding. We know the Court did not make this holding because of the structure of Part III.A, III.B, III.C, and III.D of Chief Justice Roberts's controlling opinion.

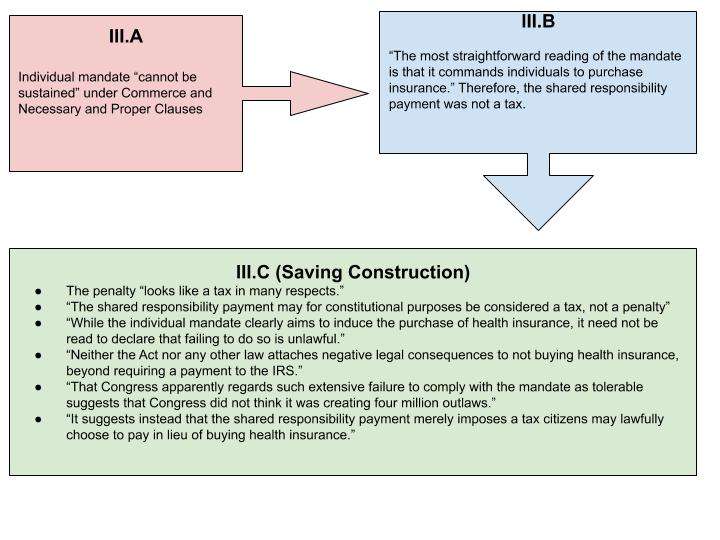

I offered the following description of this structure on pp. 9-11 of my article, Undone (which was cited by Judge O'Connor):

In Part III.A.1, the Chief Justice found that the individual mandate "cannot be sustained under a clause authorizing Congress to 'regulate Commerce.'" In Part III.A.2, the Chief Justice concluded that the mandate cannot be "upheld as a 'necessary and proper' component of the insurance reforms." That is, Congress could not mandate that people purchase insurance in order to implement the guaranteed-issue and community-rating provisions—the guards against adverse selection. However, "[t]hat [was] not the end of the matter."

In Part III.B, the Chief Justice considered if "the mandate may be upheld as within Congress's enumerated power to 'lay and collect Taxes.'" He posited that "if the mandate is in effect just a tax hike on certain taxpayers who do not have health insurance, it may be within Congress's constitutional power to tax." Yet, he rejected that conclusion: "The most straightforward reading of the mandate is that it commands individuals to purchase insurance." Therefore, the shared responsibility payment was not a tax. Still, that observation was not the end of the matter.

In Part III.C., the Chief Justice developed the so-called "saving construction." He explained that "[t]he exaction the Affordable Care Act imposes on those without health insurance"—that is, the penalty that was not actually a tax—"looks like a tax in many respects." The Chief Justice then listed three guardrails in which the "exaction"—that is, the shared responsibility payment—can be construed as a tax. First, "[t]he '[s]hared responsibility payment,' as the statute entitles it, is paid into the Treasury by 'taxpayer[s]' when they file their tax returns." Second, "[f]or taxpayers who do owe the payment, its amount is determined by such familiar factors as taxable income, number of dependents, and joint filing status." Third, "[t]his process" of making the payments, "yields the essential feature of any tax: It produces at least some revenue for the Government. . . . Indeed, the payment is expected to raise about $4 billion per year by 2017." These three guardrails are essential to the saving construction.

Finally, the controlling opinion acknowledged that the shared responsibility payment can still be saved as a tax, despite the fact that it was primarily designed to "affect individual conduct," not to raise revenue. However, that design cannot be achieved unless, in the first instance, the payment can be saved as a tax. Why? All of the exactions cited by the Chief Justice raised revenue as the means to "affect individual conduct." In other words, people modified their conduct to avoid having to pay extra money to the government. For example, "federal and state taxes can compose more than half the retail price of cigarettes, not just to raise more money, but to encourage people to quit smoking." Some people will quit smoking to avoid having to pay the taxes, but even those who continue smoking will pay the tax. But Congress must have the power to enact the exaction in the first place. Critically, Justice Ginsburg, as well as Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan, joined Part III–C of the Chief Justice's opinion. As a result, there were five votes for the proposition that the individual mandate could be upheld as an exercise of Congress's Taxing Power.

I've created a diagram to explain Part III of Chief Justice Roberts's controlling opinion.

During oral argument, Texas Solicitor General Kyle Hawkins concisely explained why Part III.A is the only relevant portion of NFIB; parts III.B and III.C are now irrelevant: (starting at 56:36)

Hawkins: My friend Mr. Letter is seriously misreading the Supreme Court's decision in NFIB. NFIB holds that the individual mandate is unlawful. It holds that 5000A(a) is best read as a command to buy insurance. And it held that that command, despite being unlawful, can only be saved if it is fairly possible to read the law as a tax. It follows, if the law cannot fairly be read as a tax, then the original holding stands and the mandate is unlawful. I think it is crucial to understand the structure of Chief Justice Roberts opinion to see how he gets there. In Part III.A of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion, he looks at the mandate. Only the mandate. Not the penalty. He says that the best way to read that is as a command to buy insurance. And then he says two things about it… That it's a command to buy insurance. And two, that command cannot be justified by the Commerce Clause or by the Necessary and Proper Clause. That's the end of III.A. He then shifts gears. In III.B and III.C of his opinion, where he says, given our holding in Part III.A we need to determine whether there is some way to save the individual mandate. And that's what he finds out in III.B and III.C is that given the fact that there is a penalty provision, and given that the penalty is raising revenue for the government, he says that we can glue the individual mandate provision to the penalty provision, and once they are glued together, then they function as a tax. Such that the law can be saved by construing it as a tax, and that tax is available under the federal government's taxing power. Now what happened in 2017 is Congress took away everything that supported III.B and III.C of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion. This [penalty] is no longer raising any revenue for the federal government. It no longer can be fairly characterized as a tax. So in light of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Part III.B and IIII.C of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion are irrelevant. The only thing we are left with then is Part III.A of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion, where he holds that is a command to buy insurance.

At that point, Judge Elrod asked if the court should "sever" Parts III.B and III.C from NFIB. Exactly! I framed the analysis this way in Undone:

Therefore, the predicate of Part III.C of the controlling opinion in NFIB is no longer relevant. Or, to put it differently, Part III.C has now been severed from the opinion.

Virtually every critic of Texas treats Part III.C as controlling. It isn't. Indeed, all of Chief Justice Roberts's observations in Part III.C were hedged, offered as conditional statements. For example:

- "While the individual mandate clearly aims to induce the purchase of health insurance, it need not be read to declare that failing to do so is unlawful."

- "That Congress apparently regards such extensive failure to comply with the mandate as tolerable suggests that Congress did not think it was creating four million outlaws."

- "It suggests instead that the shared responsibility payment merely imposes a tax citizens may lawfully choose to pay in lieu of buying health insurance."

None of these statements are premised on the best reading of the ACA; rather, they can only be supported in light of the saving construction; a construction that is no longer permissible. Part III.A held that the mandate was unconstitutional. Section 5000A was only saved by virtue of that saving construction.(I am perplexed by co-blogger Jonathan Adler's assertion that Randy and I argued that the mandate was somehow "resuscitated" by the 2017 tax bill. Zeroing out the penalty in no way affected the mandate, which was a separate statutory provision. Indeed, we made the exact opposite claim: the mandate has been unconstitutional since 2012.)

Hawkins offered this explanation:

Hawkins: Your honor, I think we read the Supreme Court's opinion fairly in light of subsequent events. It is crucial to do so here. The entire basis for III.B and III.C is now off the table. Now Chief Justice Roberts in IIIA holds that this is a command, not justifiable. That is fully supported by the four dissenting Justices. There is no doubt, there were five votes, that it is a command not justifiable by the commerce power or necessary and proper clause.

Perhaps you don't believe me. Maybe you argue that this reading of NFIB is incorrect, and that Part III.C is still the holding, regardless of the saving construction. If so, look no further than Part III.D of NFIB. It is only two paragraphs, but Chief Justice Roberts explains the structure of his own opinion:

Justice Ginsburg questions the necessity of rejecting the Government's commerce power argument, given that §5000A can be upheld under the taxing power. But the statute reads more naturally as a command to buy insurance than as a tax, and I would uphold it as a command if the Constitution allowed it. It is only because the Commerce Clause does not authorize such a command that it is necessary to reach the taxing power question. And it is only because we have a duty to construe a statute to save it, if fairly possible, that §5000A can be interpreted as a tax. Without deciding the Commerce Clause question, I would find no basis to adopt such a saving construction. The Federal Government does not have the power to order people to buy health insurance. Section 5000A would therefore be unconstitutional if read as a command. The Federal Government does have the power to impose a tax on those without health insurance. Section 5000A is therefore constitutional, because it can reasonably be read as a tax.

Section 5000A can no longer "reasonably be read as a tax." Therefore, we are left with a statute that "reads more naturally as a command to buy insurance." And "[t]he Federal Government does not have the power to order people to buy health insurance." As a result, Section 5000A(a) is now unconstitutional because it "read[s] as a command."

Part III.C of NFIB saved Section 5000A as a whole--with the mandate and penalty glued together as a "tax" on going uninsured. That opinion did not hold that the mandate (Section 5000A(a)), in particular, was constitutional. Kyle Hawkins, the Texas Solicitor General, explained this premise during oral argument:

Hawkins: The best evidence that I'm right about this is Justice GInsburg's dissent. In dissent she faults Chief Justice Roberts for discussing the commerce clause, for reaching the commerce clause holding. Justice Ginsburg said, look, this is obviously is a tax, and just say that it is a tax and be done with it. We don't have to say anything about the commerce clause. But Chief Justice Roberts rejected that. And this is in Part III.D of his opinion. He responds to Justice Ginsburg III.D and he says, no, I have to reach a commerce clause holding because this is best read as a command to buy insurance. So I have … to give it the best reading possible. Then I have to assess whether that best reading is constitutional or not. And only after doing that analysis, then do I get to the taxing issue. I think that interplay between Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Ginsburg shows that our reading is correct, and the other side's reading is incorrect because it elides the differences between those four different parts of Section III of Chief Justice Roberts's opinion.

At bottom, NFIB held that Section 5000A(a) creates a free-standing obligation. That obligation was unconstitutional in 2012. It was unconstitutional in 2017. And it is unconstitutional in 2019. Section 5000A(a) could be read as offering a "choice" to taxpayers from 2012 through 2017. Chief Justice Roberts reached this conclusion, as did then-Judge Kavanaugh. But Section 5000A(a) can no longer be read that way. Now, under the reasoning of both Roberts and Kavanaugh, plus that of the remaining joint-dissenters (Justices Thomas and Alito), Section 5000A(a) imposes an unconstitutional command to buy insurance.

Show Comments (135)