When Did Play Become Occupational Therapy?

Every kid is special, but not every kid has special needs.

The "Walking Wings Learning to Walk Assistant" is a vest that goes around your baby with long straps on the top that you can yank to pull him or her upright, like a marionette. According to the product website: "When the child is strapped into the safety harness, they can be held up by an adult walking behind them. This encourages the child's natural instinct to use their legs and develop muscle strength."

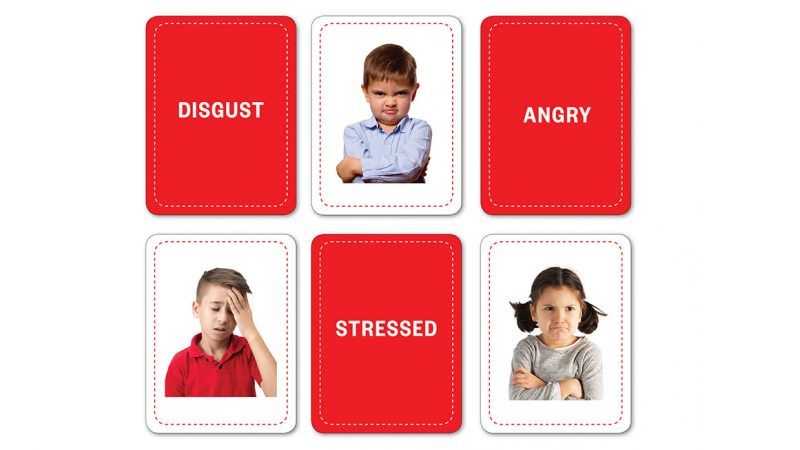

A set of emotion flash cards boasts: "Teach your student emotional intelligence (EQ). IQ gets you through school but EQ gets you through life!" According to the product description, "a high quality photograph on the front of each card teaches a child to label emotions" while "the back of each card teaches a child how these emotions feel and when they could occur." You'll be delighted (lips curving up, not down!) to learn the emotions pictured include "happy, sad, angry, frustrated, excited and many more."

The Gymboree website promises climbing equipment where children can develop "strength, balance, coordination and self-confidence."

A bumpy ball isn't just fun, its packaging explains—it aids in "sensory play."

If these products and services were only for children with developmental obstacles, such as cerebral palsy or autism, of course they'd make sense. Some kids do need help walking or reading faces. But "many of these items that came originally from the field of special needs moved into the mainstream," says Tovah Klein, author of How Toddlers Thrive (Touchstone) and director of the Barnard College Center for Toddler Development. More and more they're being marketed to parents of neurotypical children, as if trusting some basic skills to kick in on their own is an iffy—or at least time-wasting—proposition.

When Raymond Raad and his husband take their 2-year-old to the kiddie gym, the boy does not get to just run around. "I tried to sign up for free play time," says Raad, a New Jersey psychiatrist, "but you cannot."

First the children must be formally instructed in the fine art of tumbling. "There's a lot of just telling them, 'We're going to do this now. Now we're going to do that,'" says Raad.

Ah, but at the end of the session, parents can be sure this time has not been wasted. "They present you with all the things the kids have learned: 'They developed their cognitive abilities, their social abilities, their physical abilities,'" says Raad. "It is quantified."

That, in a nutshell, is childhood today. Kids may come into the world burning to play, do, learn, tumble, but adults have decided this cannot happen without a lot of intervention, supervision, and assistance. Increasingly, in fact, all children are treated as if they have special needs. They are assumed to require help with even basic functions.

"The message is that if you don't teach your child this, they may not be good at it," says Barnard's Klein—this being anything from hand-eye coordination to enjoying music. "And if they're not good at it, they may miss out."

The problem, as she sees it, is that marketers are speaking to a generation of parents already primed to worry that their infant children could fall behind from day one and, as a result, miss that slot at Harvard.

But the gadgets and programs pushed by the child assistance complex represent "a disrespect for children or a misunderstanding of what early development is," Klein says. "The reason children play is because they are driven to the core to explore their world." They don't need special toys to kickstart empathy. They don't need special ramps to learn coordination. They just need a little space and time. "The child who can't climb up the steps of the ladder keeps trying it until one day they miraculously can. They don't have to be taught to do that."

Jessica Smock, a writer, former teacher, and mom of two, has watched this devaluing of kids' natural abilities go mainstream. "Your average kid doesn't need sensory bins," she says, referring to containers filled with different-textured materials. These were originally an intervention to help children with sensory issues acclimate to touching things that might disturb them. "Now," says Smock, they're "part of the regular preschool curriculum."

Obviously, it's not terrible that kids are touching different textures. What's terrible is treating all kids as if touching different textures would automatically be a challenge for them. Equally appalling is the idea that only a specially designated sensory bin offers enough textural experience to jumpstart their development. As Smock points out, "everything is sensory." A piece of bread. A rug. A tree.

"This is a view of life that seems to emanate from the laboratory rather than family life," says Jan Macvarish, author of Neuroparenting: The Expert Invasion of Family Life (Palgrave MacMillan) and a sociologist at Britain's University of Kent. Rather than trusting a competence or curiosity to develop organically, parents are being told that knitting their child's synapses depends entirely on the stuff they do or buy. "You're supposed to do tummy time, followed by singing time," says Macvarish, outlining the kind of schedule parents heed. "It's this incredible task-based, goal-based way of being with a child. It robs the pleasure [out of parenting] and fills it with anxiety and worry."

What the adults in our culture are forgetting (thanks to all the warnings, milestones, and marketing that bombard them) is that childhood is not therapy. Or at least it shouldn't all be therapy, whether your child has special needs or not.

Kids are hardwired to learn some things—maybe most things—without the latest gadget or class. Not every moment needs be "teachable." Not every toy needs to be educational. Once parents realize this, they can stop being so worried and sad (lips pointing down!).

Show Comments (4)