The Hunt for Stoned Drivers

What sort of danger does marijuana pose on the road, and what should police do about it?

Kali Su Schram did not cause the crash that killed Ralph Martin. She nevertheless received a six-month jail sentence, followed by two years of probation, and had to pay more than $7,000 in fees and restitution as a result of the accident, which happened when Martin, a 64-year-old bicyclist, rode into Schram's path as she was driving on Seaway Drive in Muskegon, Michigan, on the morning of November 26, 2015.

Schram, who was 20 when she was sentenced in 2017, had tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), marijuana's main psychoactive ingredient, in her blood at the time of the collision. There was no evidence that Schram was impaired by marijuana, let alone that it contributed to the accident. Nor was she at fault, since she had the right of way when Martin suddenly appeared in front of her car at an intersection. "If you read the police report," Schram's lawyer told the Muskegon Chronicle, "she could not have done anything to avoid this particular accident."

None of that mattered, because in Michigan it is illegal to drive with "any amount" of a Schedule I controlled substance in your body. According to the Michigan Supreme Court, an inactive metabolite of marijuana does not count as a Schedule I drug, but THC does, even at levels too low to impair driving ability. In a separate case, the court said Michigan's "zero tolerance" rule does not apply to patients who are authorized by the state to use marijuana for medical purposes. But it does apply to other cannabis consumers, even now that recreational use is legal in Michigan, unless legislators change the law or courts read another exception into it.

Unlike Michigan's legalization initiative, which voters approved in 2018, Washington's, which passed in 2012, specifically addressed marijuana-impaired driving. The initiative established a "per se" rule that makes a driver guilty of driving under the influence (DUI) when his THC blood level meets or exceeds five nanograms per milliliter. But that rule also has created problems, since regular cannabis consumers may exceed the threshold even when they are not impaired.

One of the first drivers charged under Washington's new law was Ronnie Payton, a 65-year-old Vietnam veteran who used marijuana to treat his glaucoma. On Christmas Day in 2012, Payton was arrested for DUI after a minor car accident in Renton. A blood test found his THC level exceeded the legal threshold by 3.6 nanograms, even though the last time he had smoked pot was about 12 hours before the accident. He would have been automatically convicted if his lawyer had not managed to stop prosecutors from using the blood test during his trial.

THC blood levels do not correspond directly to degrees of impairment.

If setting the THC limit for driving at zero or at five nanograms per milliliter can produce perverse results like these, what should the cutoff be? It's a trick question. As Staci Hoff, research director at the Washington Traffic Safety Commission, observed in a 2017 interview with a Seattle TV station, "More and more research is coming out debunking this mythical link between THC level in the blood and level of impairment." A 2016 study sponsored by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, for instance, concluded that "a quantitative threshold for per se laws" based on THC in the blood "cannot be scientifically supported." Or as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) put it in a 2017 report to Congress, the level of THC in a driver's blood "does not appear to be an accurate and reliable predictor of impairment."

THC, unlike alcohol, is fat-soluble rather than water-soluble, so there is no clear or consistent relationship between THC in the blood and THC in the brain, which means THC blood levels do not correspond directly to degrees of impairment. Complicating the situation further, individuals vary widely in the way they respond to a given dose of THC, especially when you compare occasional marijuana users to regular consumers, who may develop tolerance to the drug's effects or learn to compensate for them.

Patients who use marijuana as a medicine and other daily cannabis consumers can test positive for THC days after their last dose, and they may be competent drivers at THC levels far above Washington's cutoff, while naïve or occasional users may be a menace even when they fall below it. Any definition of stoned driving that is based on THC blood levels will implicate innocent people and give a pass to drivers who are seriously impaired. Zero-tolerance laws, which a dozen states have, avoid the latter problem, but only at the cost of criminalizing cannabis consumers who drive, regardless of whether they are impaired.

That reality creates a quandary for states that decide to legalize marijuana. Experiments show cannabis impairs performance on simulators and driving courses, although its effects are not nearly as dramatic as alcohol's. Marijuana's impact on traffic fatalities in the real world is harder to measure, and it is not clear that legalization magnifies the problem. But it makes sense to worry about the possibility, since legal access tends to increase cannabis consumption, which could mean more stoned drivers on the road.

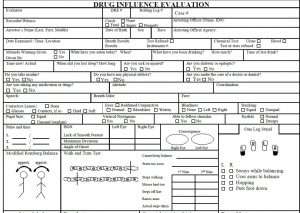

The challenge is figuring out who they are. Since toxicological tests cannot prove impairment by marijuana, additional evidence is needed. In the United States, Canada, and a few other countries, that evidence is often collected by "drug recognition experts" (DREs)—police officers who are trained to administer a 12-step protocol that includes an interview, vital sign measurements, eye examinations, and sobriety tests. But while some of these measures seem to be good indicators of marijuana use, they do not necessarily prove someone is too intoxicated to drive.

Critics of the DRE program, which was developed by the Los Angeles Police Department and is managed by the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), say it has never been properly validated. They argue that a DRE's interpretation of test results can be skewed by his expectations and that his ultimate assessment is largely subjective. Supporters of the program argue that "nothing in or about the DRE protocol is new or novel," as the IACP puts it, and that it is the best currently available alternative to per se laws that unjustly and irrationally treat sober drivers as if they were stoned.

'It Basically Slows Everything'

Laboratory experiments show marijuana affects cognitive abilities that are related to driving. "The most important one is executive function," says Marilyn Huestis, a forensic toxicologist who spent 23 years at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, where she studied the effects of cannabis consumption. Executive function refers to "the set of higher-order processes (such as inhibitory control, working memory, and attentional flexibility) that govern goal-directed action and adaptive responses to novel, complex, or ambiguous situations," as the textbook Comprehensive Developmental Neuroscience puts it. "All aspects of executive function are affected by cannabis," Huestis says. "It basically slows everything."

In experimental studies that look at performance on driving simulators or road tests, the most common cannabis effects include increased reaction time, greater weaving within the lane, and poorer performance on tasks that require divided attention. Subjects under the influence of marijuana, unlike those under the influence of alcohol, tend to be aware of their impairment and try to compensate for it by driving more slowly and cautiously. There is some evidence that marijuana and alcohol together impair driving ability more than either alone, although not all researchers agree on that point.

Alcohol has a much bigger impact on driving ability than marijuana does, and the practical significance of the cannabis effects measured in experiments is a matter of debate. "There is a real question of how big these impairments are," says Michael White, a psychologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia, where it is illegal to drive with any detectable amount of THC in your blood. White found that marijuana's effect on a driver's ability to maintain lateral position within his lane, for example, is similar to the decline seen with 10 years of aging. He also notes that researchers found "it was very difficult to detect any impairment at all in regular users," who probably account for most of the THC-positive drivers on the road at any given time.

"People under the influence of marijuana tend to drive differently," says Paul Armentano, deputy director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). "The practical question is what correlation, if any, exists between these changes in behavior and increased accident risk."

Alcohol has a much bigger impact on driving ability than marijuana does.

That question has proven difficult to answer. Epidemiological studies that try to measure the crash risk associated with marijuana use are plagued by methodological problems, including inappropriate controls, failure to adequately consider confounding variables, and improper classification of sober drivers as stoned (and vice versa). "The main challenge is that we have noisy and imprecise methods, which makes it hard to pin down small risk increases," says Norwegian economist Ole Rogeberg, who has studied marijuana's impact on road safety.

Two meta-analyses published in 2012 found that cannabis consumption roughly doubles the risk of a crash, which is the estimate that Huestis favors. To put that number in perspective, a 2016 study sponsored by NHTSA found that a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 0.08 percent, the current DUI threshold in almost every state, was associated with a fourfold increase in crash risk, while a BAC of 0.10 percent, the old cutoff, nearly sextupled the risk. But even the relatively modest twofold risk increase that is commonly attributed to marijuana may be an exaggeration.

Rogeberg and Rune Elvik, a road safety researcher at the Institute of Transport Economics in Oslo, co-authored a 2016 meta-analysis that sought to correct errors in the earlier estimates. "A major problem in both meta-analyses was that they failed to use adjusted estimates from the studies they were pooling," Rogeberg says. "Comparing THC-positive and THC-negative drivers with the same sex and similar ages, you find a much lower risk increase. In addition, we found that both studies had made errors when extracting data from the underlying studies, and that they combined estimates that were not estimating the same thing."

Rogeberg and Elvik's meta-analysis, published in the journal Addiction, found "the average risk increase associated with cannabis intoxication and recent use" was more like 35 percent, which Elvik compared to the added risk associated with driving at night rather than during the day. After that analysis was published, Dalhousie University epidemiologist Michael Asbridge, the lead author on one of the 2012 studies indicating a doubling of risk, told The Leaf, a cannabis news site, he thinks "the true estimate lies somewhere between their revised estimate and our estimate."

Michael White did his own review of what he identified as "the best epidemiological evidence" in 2017 and concluded that "if cannabis does increase the risk of crashing, the OR [odds ratio] is unlikely to be greater than about 1.3"—i.e., a 30 percent risk increase. A 2018 meta-analysis of two dozen studies, published in Frontiers in Pharmacology, found that "publication bias was very high," meaning studies that find marijuana increases crash risk are much more likely to see print than studies that don't, and that the overall association "is not statistically significant." By contrast, a 2019 meta-analysis published in The Canadian Journal of Addiction, based on a smaller set of studies, calculated a statistically significant odds ratio of about 2.5, representing a 150 percent risk increase.

NHTSA's 2016 crash risk study in Virginia Beach, Virginia, which the agency described as the "largest and most comprehensive study" of its kind, shows why methodology matters. The researchers matched each of 3,000 drivers who were involved in crashes with two drivers who were not but who were on the road in the same location on the same day of the week at the same time and traveling in the same direction. The initial analysis found that drivers who tested positive for THC were 25 percent more likely to be involved in crashes. But that difference disappeared once the researchers took into account age, gender, race/ethnicity, and alcohol use.

Those results suggest that recent cannabis consumption could be an indicator of other variables that independently affect crash risk. "If the THC-positive drivers were predominantly young males," NHTSA noted, "their apparent crash risk may have been related to age and gender rather than use of THC." White thinks that observation may explain the results of other studies that did not adjust for confounding variables. "What they report as a marijuana effect might well be a young man effect," he says. Young men are especially likely to be cannabis consumers and especially prone to crashes even when they are perfectly sober. Furthermore, the sort of young men who think nothing of getting behind the wheel right after smoking pot are probably more reckless than the ones who decide that's not such a good idea.

Then again, the NHTSA study may have underestimated marijuana's impact on crash risk because it treated all THC-positive drivers as if they were under the influence, when some of them probably were not. Recent simulator studies have found that performance is no longer affected two or three hours after smoking pot, although THC can still be detected by blood tests at that point. Putting THC-positive-but-unimpaired drivers in the marijuana-exposed group would tend to reduce the apparent crash risk.

What they report as a marijuana effect might well be a young man effect.

A related issue in other crash risk studies is the lag between an accident and obtaining a blood sample. The NHTSA study included a data collector who was a licensed phlebotomist, so samples were drawn promptly. But ordinarily blood may not be obtained until one to three hours after a crash, which could be enough time for THC blood levels in some drivers to fall below the detection threshold. To the extent that happens, drivers who were under the influence when they got into accidents could be misclassified as drug-free. If the same thing happens with drivers who were not involved in accidents, however, the apparent crash risk would be unaffected.

Does Legalization Mean More Crashes?

If driving under the influence of marijuana increases the risk of a crash by 30 percent, or even 100 percent, it is surely not a wise or responsible choice, but it is still much less dangerous than driving while drunk and no more dangerous than other hazards that do not generate the same opprobrium or legal sanctions. "Turning on the radio increases the risk of accident almost twofold," NORML's Paul Armentano says. "Driving with more than two passengers in the car increases one's risk of accident more than twofold. Obviously, texting while driving dramatically increases one's risk of accident. On the spectrum of risk, being under the influence of marijuana is at the low end. Public safety campaigns and the law need to provide that kind of perspective."

Given the relatively small hazard posed by marijuana, legalizing it would not necessarily lead to more traffic fatalities. To the extent that marijuana serves as a substitute for alcohol, legalization might even improve road safety by replacing severely impaired drinkers with modestly impaired cannabis consumers.

A 2013 study reported in The Journal of Law & Economics found evidence of such an effect in states that legalized medical use of marijuana, which saw a 9 percent drop in traffic fatalities compared to states that did not, apparently due to a reduction in alcohol consumption. A 2017 study reported in the American Journal of Public Health likewise found that medical marijuana laws were associated with reductions in traffic fatalities.

So far there is not much evidence of a substitution effect in states that have legalized recreational use. But neither is there much evidence that legalization has made fatal crashes more common.

A 2016 study by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety found that in Washington, which legalized marijuana in 2012, the share of drivers in fatal crashes who tested positive for THC stayed about the same in 2013 but doubled in 2014. Although state-licensed marijuana stores began serving recreational customers in July 2014, the authors said, "it was not possible to evaluate the impact of the opening of marijuana retail stores on the prevalence of THC-positive drivers in fatal crashes, because this occurred only 6 months before the end of the study period." The likelihood that drivers would be tested for drugs rose during the study period, but the researchers used imputation methods to estimate results for untested drivers.

The authors of the study noted that "drivers who had detectable THC in their blood at the time of the crash were not necessarily experiencing impairment in their ability to drive safely, nor were they necessarily at fault for the crash." In other words, the increase in THC-positive test results may reflect a general increase in cannabis consumption, as opposed to an increase in crashes caused by marijuana. "They are identifying that marijuana is more prevalent in drivers today than it was in the past," Armentano says. "That tells us nothing about accident risk."

Legalization might even improve road safety by replacing severely impaired drinkers with modestly impaired cannabis consumers.

That point applies with even greater force to data highlighted by the Rocky Mountain High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, an anti-drug task force that claims the number of "traffic deaths related to marijuana" doubled between 2013 and 2016 in Colorado, where marijuana was legalized in 2012. Those cases include all fatal crashes where a driver tested positive for any amount of THC or an inactive metabolite, so there is even less reason to assume marijuana contributed to the deaths.

If we want to know whether legalization increases traffic fatalities, the relevant question is whether states that allow recreational use see more of them than would otherwise have been expected. According to a 2017 study published in the American Journal of Public Health, "changes in motor vehicle crash fatality rates for Washington and Colorado were not statistically different from those in similar states without recreational marijuana legalization." A 2018 working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research reached a similar conclusion about those two states, finding that "synthetic control groups saw similar increases in marijuana-related fatality rates despite not legalizing recreational marijuana."

A 2019 study published in Addiction, by contrast, found that after legalization "traffic fatalities temporarily increased by an average of one additional traffic fatality per million residents" in Colorado, Washington, and Oregon as well as neighboring states. On the whole, Armentano says, the data indicate that "you can change the legal status of marijuana" without having "a significant adverse effect on traffic safety."

Could It Be Drugs?

Such assurances, of course, are little comfort to the families of people killed in crashes caused by stoned drivers. In 2016, for instance, 43-year-old Amanda Walzer was killed and her 49-year-old fiancé, Jon Warshawsky, suffered a brain injury when a Toyota Corolla crossed the center divider and collided head-on with their vintage Porsche sports car on Pomerado Road in San Diego. The driver of the Corolla, 36-year-old Hyun Jeong Choi, had just smoked marijuana she bought at a nearby dispensary. Police found an open bag of marijuana and a recently used pipe in her car. Choi, who in January was convicted of gross vehicular manslaughter while intoxicated and DUI causing injury, said she "tried to fight it" and "tried to get home" after smoking the pot, which was stronger than she expected.

The desire to identify such dangerously impaired drivers before they hurt or kill anyone was one of the main motivations for the DRE program. As a Detroit police officer in the late 1970s, Thomas Page recalls, he would come across drivers who "were impaired" but "had little or no alcohol in them." He would wonder, "Could it be drugs?" Because police had no test to verify that suspicion, Page says, "officers like me were increasingly frustrated."

After he moved to the Los Angeles Police Department in 1981, Page helped develop a response to that problem. Partly because he had a master's degree in urban studies and had worked for the Wayne County Health Department while attending graduate school, he was asked to help coordinate a 1985 study of the DRE program, which the LAPD had recently established to fill the gap that frustrated Page and his fellow officers. The DRE protocol combined "field sobriety tests" that had been developed for alcohol, such as the walk-and-turn and finger-to-nose tests, with an interview and other indicators thought to be affected by drug use, such as pulse, blood pressure, pupil size, and visual tracking.

The L.A. study, conducted by NHTSA researcher Richard Compton, looked at DRE evaluations of 173 suspects who had been arrested for driving under the influence of drugs other than (or in addition to) alcohol. The DRE officers concluded that all 173 suspects were impaired by illegal drugs, and blood tests found substances other than alcohol in all but 11 cases. That finding is often reported as a 94 percent accuracy rate, which sounds impressive but is misleading for several reasons.

First, the rate at which the officers correctly identified the drugs suspects had taken was lower. They were "entirely correct" (meaning they named all the drugs detected) 49 percent of the time, "partially correct" (meaning they named at least one of the drugs detected) 38 percent of the time, and "wrong" (meaning none of the drugs they named was detected) 13 percent of the time. When a DRE concluded that a suspect was high on marijuana, the blood test found THC 78 percent of the time.

Second, all of the subjects had already been arrested for driving under the influence of drugs, based on evidence such as erratic driving, slow responsiveness, lack of balance, drugs found in the car, and admissions of drug use. "This method skewed the study sample towards drug impairment," notes Greg Kane, a physician and medical malpractice expert, in a 2013 critique published by the Journal of Negative Results in BioMedicine. "The DRE opinions were correct 94% of the time—because 94% of the sample group had drugs present." Hence that figure "reveals not the diagnostic accuracy of the [DRE evaluation], but the prevalence of drugs in the sample population."

Third, the blood tests did not actually confirm that the suspects were impaired by drugs, which is what the DRE protocol is supposed to detect. "The fact that drugs were found in a suspect's blood does not necessarily mean the suspect was too impaired to drive safely," Compton wrote. "Contrary to the case with alcohol, we do not know what quantity of a drug in blood implies impairment. Thus, this study can only determine whether a drug was present or absent from a suspect's blood when the DRE said the suspect was impaired by that drug."

The politicians want a quick fix, and this is what they've come up with.

In addition to the LAPD study, Kane considered a 1994 field study in Phoenix and a 1985 laboratory study. These three studies, all of which were funded by NHTSA, are commonly cited as validating the DRE protocol. But Kane found they "did no reference testing of driving performance or physical or mental impairment, investigated tests different from those currently employed by U.S. law enforcement, used methodologies that biased accuracies, and reported DIE [drug influence evaluation] accuracy statistics that are not externally valid." Kane concluded that these studies "do not quantify the accuracy of the DIE process now used by U.S. law enforcement" and "do not validate current DIE practice."

Scott Macdonald, an epidemiologist and biostatistician at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, reviews the evidence in favor of the DRE process in his self-published 2018 book Cannabis Crashes: Myths & Truths. "The DRE protocol is not a scientifically valid technique for proving that an individual has consumed a particular class of illicit drug resulting in impairment," he writes, although "officers are able to identify drug classes with an accuracy better than chance." And while "DRE assessments are considered the gold standard for impairment, they have not been validated against a reasonable threshold for impairment using any type of biological test."

David Rosenbloom, a drug expert at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, is similarly skeptical of the DRE protocol, which the Canadian government has endorsed. "We're just at the beginning of developing tests for impairment," he says. "The politicians want a quick fix, and this is what they've come up with. The legislation [backing the DRE program] got passed based on reliability, not validity. Reliability is really a test of repeatability. So yeah, you're getting the same results over and over, but it doesn't mean anything, because it's not valid."

Name That Drug

These critics have a point, but that does not mean DRE evaluations have no value as evidence of stoned driving. Some laboratory studies have found that DRE techniques are helpful in determining which drug subjects have taken. In the 1985 study that Kane reviewed, for instance, officers missed a lot of the subjects who had been given drugs, especially when the doses were low. But when they judged the subjects to be intoxicated, they generally picked the right drug out of four possible choices. Although the officers incorrectly put pot smokers in the placebo group 45 percent of the time, they were correct in all but one case when they concluded that a subject had consumed cannabis.

In other laboratory studies, DRE methods look less impressive. "When DREs concluded impairment was due to drugs other than ethanol," a 1996 study reported in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology found, "their opinions were consistent with toxicology in 44% of cases." A 2005 study reported in the journal Accident Analysis & Prevention found an alarming false positive rate of 57 percent. The officers correctly identified subjects under the influence of cannabis about half the time, but nearly a third of the subjects they thought had smoked pot actually got the placebo.

Another 2005 study, reported in Forensic Science International, focused on the correspondence between field sobriety tests (FSTs), a major component of the DRE assessment, and marijuana-impaired performance on a driving simulator. In the low-dose condition, 89 percent of subjects scored as impaired on the driving simulator were correctly identified by the FSTs, but 61 percent of the subjects who did fine on the driving simulator nevertheless failed the FSTs. In the high-dose condition, the FSTs identified 92 percent of impaired drivers but incorrectly classified 85 percent of the unimpaired drivers as impaired. The researchers concluded that "performance on the [FSTs] provides a moderate predictor of driving impairment following the consumption of THC."

Supporters of the DRE program argue that the laboratory studies are unrealistic because they do not include the entire DRE protocol, because the stakes are different (so officers may be more inclined to guess), and because the drug doses are lower than the ones police typically encounter. Another significant difference is that laboratory subjects take just one out of four or five drugs at a time, while drivers pulled over by the police are often under the influence of multiple drugs. While all of that is true, the laboratory studies have the advantage of testing DRE methods in a controlled setting. In the real world, it is harder to tell what is going on.

A 2016 study sponsored by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, for instance, compared 602 drivers who had been arrested for driving under the influence and had tested positive for THC but no other drugs to 349 "drug-free controls," mainly volunteers who underwent DRE evaluations "for training purposes or for their own interest." The controls did much better than the arrestees on three FSTs: the walk-and-turn, one-leg-stand, and finger-to-nose tests. But that is hardly surprising, since these drivers were charged with DUI based partly on their FST performance. Likewise, it makes sense that indicators such as "red, bloodshot and watery eyes," "rebound dilation" (widening of pupils after constriction in response to a bright light), "lack of convergence" (the failure to cross your eyes while tracking an object as it moves toward your nose) were more common among DUI arrestees, since those are clues that police use to identify drug-impaired drivers.

A similar study, co-authored by Marilyn Huestis and published the same year in Accident Analysis & Prevention, compared 302 THC-positive arrestees to 302 "non-impaired individuals," mainly police officers undergoing DRE training. The researchers found that the finger-to-nose test "best predicted cannabis impairment." Eyelid tremors during the modified Romberg balance test—which requires the subject to estimate the passage of 30 seconds while standing with his feet together, eyes closed, and head back—were a close second. "Other strong indicators" included rebound dilation, swaying during the one-leg stand, and two or more mistakes during the walk-and-turn test.

The differences between the two groups may have been magnified by the police officers' greater familiarity with the FSTs. Leaving that point aside, the "strong indicators" were the characteristics that distinguished THC-positive DUI arrestees, selected based partly on those very criteria, from sober police officers. They are not necessarily the characteristics that distinguish dangerously impaired drivers from sober ones. Neither THC-negative drivers who fail DRE evaluations nor intoxicated drivers who pass them would be included in a study like this one.

Supporters of the DRE program argue that the laboratory studies are unrealistic.

In addition to the tests highlighted by these studies, the full DRE protocol, which takes about an hour to complete, includes interviews with the suspect and the arresting officer. Those conversations may reveal details like these: The suspect drove erratically, had trouble rolling down his window, fumbled for his license, had difficulty answering questions, staggered as he walked, smelled like marijuana, had a bag of weed on the front seat, and/or admitted that he had recently smoked pot. These are, to be sure, relevant pieces of information that are not available to a DRE participating in a laboratory study. But they may influence the officer's interpretation of test results, his perception of intoxication clues such as swaying or red eyes, his inquisitiveness about alternative explanations for such clues, and his ultimate conclusion about whether the driver is impaired and, if so, by what.

That tendency "is what we call confirmation bias," says David Rosenbloom, the Canadian drug expert. "You confirm what you're thinking all along, as opposed to what is true."

Thomas Page, who ran the LAPD's DRE program for 10 years, is familiar with the problem. "It's a danger," he says. "Certainly we're aware of that possibility. That comes up very, very often. The officer needs to take that into consideration." He notes that a DRE may end up disagreeing with an arresting officer who thinks a driver is impaired. That happened in 18 of the original 219 DUI cases identified in the 1985 LAPD field study, and those drivers were released.

Shira Stefanik, a Seattle defense attorney who specializes in DUI cases, argues that DREs, given the context in which they are deployed, are inclined to conclude that drivers are impaired. "If a cop pulls you over and thinks you're impaired and is asking you to get out of the car to take these tests," she says, "more often than not they already think you're impaired, and they're running you through this battery to enhance their report later on. The cops are looking for certain clues and plugging them into a mental spreadsheet of what substances the person could potentially be on. I don't find that they're looking for alternative explanations. They're looking to justify their arrest and possibly help a conviction, depending on how those blood results come back."

Green Tongues and Red Flags

First impressions are important because many clues identified by DREs are ambiguous. Ideally, police would compare a driver's current condition and performance with his condition and performance when he is sober. But DREs have no baseline information, so they rely instead on averages and on assumptions about what a sober person should look like and be able to do. Bloodshot eyes might indicate cannabis consumption, or they might indicate fatigue or allergies. A fast pulse might be a sign of marijuana use or a sign of nervousness. Lack of convergence or poor performance on sobriety tests might reflect the effects of THC or a person's innate limitations. In the AAA study of DRE evaluations, a substantial fraction of the "drug-free controls," ranging from one-third to more than half (depending on the test) failed the FSTs.

So did Ronnie Payton, the Washington driver arrested on Christmas Day 2012. His lawyer successfully argued that stress, cold weather, glaucoma, and war injuries explained the clues that the arresting officer perceived as signs of intoxication.

"When you do a lot of field sobriety testing, what you find out is that it's not terribly useful by itself," says Teri Moore, who learned the DRE protocol from Thomas Page when she was a police officer in L.A. and eventually became a DRE instructor. "There are people who are cold sober who cannot walk a line or stand on one foot. My eyes don't converge no matter what. And there are plenty of people like that."

Moore, who is now a policy analyst at the Reason Foundation, which publishes this website and in January released a paper on marijuana-impaired driving that she wrote, says DREs are taught that it's not safe to rely on one or a few clues. They are supposed to reach a conclusion "based on the totality of the evaluation," as the IACP puts it.

Once they get out of the classroom and into the field, however, DREs do not necessarily follow the protocol to the letter. In 2017 the American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia sued the Cobb County Police Department in federal court on behalf of three sober drivers who were arrested by a DRE, Officer Tracy Carroll, based on a "watered-down version" of the 12-step protocol. Carroll pulled over all three drivers for briefly touching or crossing the line at the edge of their lanes and deemed all of them stoned despite their protests to the contrary. They were all arrested for DUI and spent a night in jail, and their charges were all eventually dropped after tests found no trace of marijuana in their blood. Carroll's bosses stood by him, saying he not only had "more than enough probable cause to arrest" but would have been justified in busting the plaintiffs for driving under the influence of marijuana even if he had already seen the blood test results showing that they weren't.

We're pretty good at making sure that we're prosecuting the right people.

Carroll rejected alternative explanations for observations he saw as evidence of marijuana intoxication, such as watery eyes. Another lawsuit filed in Georgia illustrates that pitfall even more dramatically.

On a Sunday morning in May 2006, according to a 2010 ruling by U.S. District Judge Hugh Lawson, Tift County Sheriff's Deputy Joey Budd pulled over a commercial truck on Interstate 75 because he saw smoke billowing from it. Budd noticed that the driver, Luther Smith, "was unsteady on his feet, that his speech was slow and kind of mumbled, that his shoes were on the wrong feet, and that he had urinated in his pants." Budd summoned a DRE, Deputy Mark Lyles, who evaluated Smith and concluded that he was under the influence of drugs.

Smith was arrested and taken to jail. That night, after his jailers noticed that he had fallen, his face was drooping, and he was drooling, they decided he needed medical attention. He was taken to a hospital and eventually died from complications caused by an ischemic stroke. At the time of the stop, Judge Lawson noted, "Budd was aware that there could be medical explanations for Smith's behavior," but "he was not in a position to rule out the possibility that Smith's behavior was caused by a medical condition and not drugs."

That sort of mistake is presumably rare. NORML's Paul Armentano says the most common issue he sees in DUID cases in which he advises defense attorneys is that "there's no evidence of impaired driving." A police officer pulls someone over for something like an expired registration sticker or a broken taillight and only afterward suspects the driver is intoxicated. "At no point does the officer make any observation of the person driving erratically," Armentano says. "And I think, 'Well, that's interesting. You've been watching this person drive for miles, and you pull them over on an administrative violation.'"

The grounds for suspecting that a driver is high sometimes seem less than scientific. The Washington State Patrol's DRE course manual, for example, lists "possible green coating on the tongue" as a sign of marijuana intoxication, and defense attorneys say descriptions of green tongues frequently show up in the reports and testimony of officers who arrest people for driving while stoned. "I frankly don't know where they got that," says Stefanik, the Seattle DUI lawyer. "Not only have I not seen any research supporting that, but in my own training and experience called college I've never seen anyone's tongue turn green after ingesting marijuana."

Page says officers are supposed to report their observations. "They see a green coating on the tongue," he says. "Does it tell them that the person has taken something into the body? Sure, it does. Could it be mints? Yes, it could be Clorets or something like that. Officers can testify to what they saw. They're certainly not going to be making a final determination whether the person's under the influence or not under the influence based on the coloration of the tongue."

By and large, Page says, "we're pretty good at making sure that we're prosecuting the right people," since supervisors, prosecutors, judges, and jurors act as checks on sloppy or overzealous DREs. If a DRE reports an unusually high rate of drivers who refuse to cooperate with blood tests, he says, that's "a real danger sign," because it may indicate that "they're afraid of something not proving them right." If it turns out that the officer is encouraging refusals, "that's grounds for removal from the program." Another "red flag," Page says, would be if a DRE claims "100 percent of the time, we're being corroborated" by blood tests.

Teri Moore says the DRE program "tends to draw the geeks" rather than "the Rambo types," and she's "never seen" DREs who deviate from the protocol, "because it's drilled into you in training that you don't do that." Consistency is vital, she says, since "the DRE process only continues to be used in court because it is quite accurate and standardized."

'The DRE Is Necessary'

U.S. courts generally admit DRE testimony as evidence in DUI cases, although they do not always treat DREs as experts.

In one of the more favorable rulings, the Washington Supreme Court concluded in 2000 that the DRE protocol was "accepted in the relevant scientific communities." It said a properly qualified DRE officer who has followed all 12 steps of the protocol "may express an opinion that a suspect's behavior and physical attributes are or are not consistent with the behavioral and physical signs associated with certain categories of drugs." But the court cautioned that "an officer may not testify in a fashion that casts an aura of scientific certainty to the testimony."

The Minnesota Supreme Court, by contrast, held in 1994 that the DRE protocol "is not in itself a scientific technique" but allowed DREs to offer nonexpert testimony. "The real issue," the court said, "is not the admissibility of the evidence but the weight it should receive, and that is a matter for the jury to decide without being led to believe that the evidence is entitled to greater weight than it deserves. Therefore, in the courtroom the officer shall not be called a 'Drug Recognition Expert.' Perhaps the officer can be called a 'Drug Recognition Officer' or some other designation which recognizes that the officer has received special training and is possessed of some experience in recognizing the presence of drugs without suggesting unwarranted scientific expertise."

Some courts have been even more skeptical. In a 2012 opinion, based on highly critical expert testimony presented by defense attorneys, Carroll County, Maryland, Circuit Judge Michael Galloway concluded that the DRE protocol "is not generally accepted as valid and reliable in the relevant scientific community." Since "the DRE training police officers receive does not enable DREs to accurately observe the signs and symptoms of drug impairment," Galloway said, "police officers are not able to reach accurate and reliable conclusions regarding what drug may be causing impairment."

An argument against the DRE process is an argument for zero tolerance.

In 2017 the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts concluded that "there is as yet no scientific agreement" about whether FSTs, which "were developed specifically to measure alcohol consumption," are a sound measure of marijuana intoxication. While FST results "are admissible at trial as observations of the police officer conducting the assessment," the court said, the officer may not say whether the defendant's performance "would have been deemed a 'pass' or 'fail,' or whether the performance indicated impairment." Furthermore, "because the effects of marijuana may vary greatly from one individual to another, and those effects are as yet not commonly known, neither a police officer nor a lay witness who has not been qualified as an expert may offer an opinion as to whether a driver was under the influence of marijuana."

One common criticism of DRE methods is that police officers have no medical expertise but are expected to make what is essentially a diagnosis: This driver's symptoms indicate that he is under the influence of Drug X. "I totally disagree with that characterization," Page says. "It's almost like asking whether it's appropriate for a mother to put her hand on a child's forehead and say, 'I think he's got a fever.'" He notes that a test such as "seeing pupils of different sizes," which DREs are taught may be a sign of a medical problem such as a seizure or a concussion, "doesn't require a medical degree." In Page's view, "we're doing a pretty darn good job."

Marilyn Huestis, who contributed to the DRE course manual, concurs. "We are a society that really wants to always protect the individual," she says, but "we also need to protect people from drug-impaired drivers. I think that the DRE program is a good program that really attempts very much to do that."

NORML's Paul Armentano thinks "the DRE is necessary," although he'd like to see more extensive training. The current program involves 72 hours (nine days) in the classroom and 40 to 60 hours of field certification. "I think the DREs are asked to be experts in far more things than they can gain expertise on in such a short period of time," Armentano says. "I do think there are components of the DRE exam that use some validated measures for distinguishing people who may or may not be under the influence. It's a good program to have, but I think the program could be a whole lot better than it is today."

Even as it is, Moore says, DRE training is "a big cost for departments." At the beginning of 2018, there were about 8,600 certified DREs in the United States, a country with more than 15,000 local law enforcement agencies. As a cheaper, less time-consuming alternative, NHTSA, which helped produce the DRE curriculum, developed a 16-hour course known as Advanced Roadside Impaired Driving Enforcement (ARIDE). But NHTSA notes that "an ARIDE trained officer who encounters a suspected marijuana-impaired driver would likely summon a DRE" to conduct an evaluation "if one is available."

According to NHTSA, "there are currently no evidence-based methods to detect marijuana-impaired driving." The agency is sponsoring research aimed at developing a handheld, tablet-based test of impairment, which if combined with roadside tests of oral fluid could help provide probable cause for DUI arrests. Like blood tests, saliva tests do not prove a driver is currently intoxicated, but they indicate relatively recent use, and the results are available much more quickly. Another possibility, Huestis says, is a cap that measures a driver's brain waves, assuming it can be shown that "their brain waves look different enough when they're high."

In the meantime, Moore says, DREs are the best available option. "It's potentially problematic because, as in much of police work, you're relying on one or two individuals who are experts at what they're doing to make an assessment on someone," she says. "It can be used to take away someone's liberty. You'd better have a good reason for doing that, and you'd better be able to articulate it. It can be abused if no one is watching."

Moore argues that dashboard and body camera video is an important safeguard, since it can document erratic driving prior to a stop and show how the driver and the officer behaved afterward. "We have to hold police officers to a higher standard," she says. "If people act badly, they need to be taken off the police force."

At the same time, Moore adds, "you have to have some means of addressing the problem of impairment by drugs," and per se laws are neither scientific nor just. "An argument against the DRE process is an argument for zero tolerance," she says. "This is what we have for now, and it has to be balanced against what would happen if we didn't have it."

[This article has been revised to clarify the impact of misclassifying intoxicated drivers in crash risk studies as drug-free.]

Show Comments (12)