The Assange Exception to the First Amendment

Freedom of the press is not limited to "legitimate journalists."

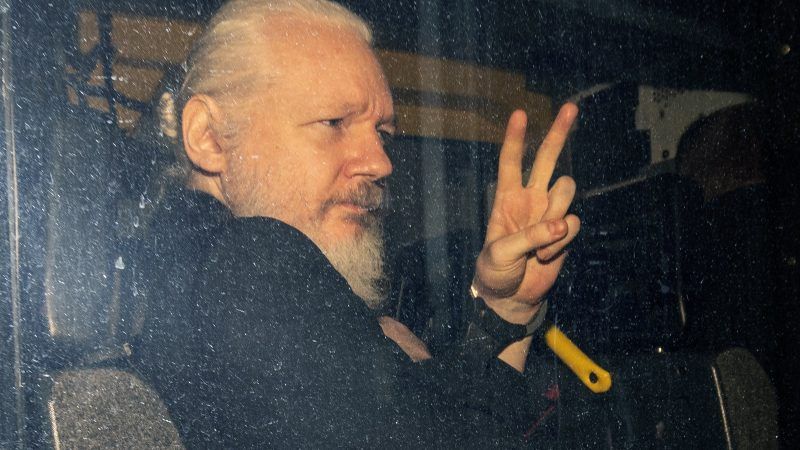

The debate about whether Julian Assange should be considered a journalist, reignited by the WikiLeaks founder's arrest in London last week, gives employees of news and opinion outlets ample opportunity to display their high self-regard and contempt for amateurs who fall short of their lofty standards. But the question is constitutionally irrelevant, because freedom of the press belongs to all of us, no matter where we work or what the journalistic establishment thinks of us.

The same goes for the limits to freedom of the press. The right to use media of mass communication does not give a journalist, no matter how public-spirited or well-respected, permission to burglarize someone's home or office in search of newsworthy information.

On its face, the federal indictment of Assange, which was drawn up in March 2018 and unsealed last Thursday, charges him with a crime akin to burglary: conspiracy to commit computer intrusion. According to the Justice Department, Assange helped former U.S. Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning gain unauthorized access to classified files on Defense Department computers.

Except that is not really what happened, since Manning already had access to those files. The thin reed on which the indictment hangs is Assange's unsuccessful attempt to crack a government password, which "would have allowed Manning to log onto the computers under a username that did not belong to her" and "made it more difficult for investigators to identify Manning as the source of disclosures of classified information."

The essence of Assange's crime, in other words, was not hacking computers or stealing secret files but trying to help a source cover her tracks—something news organizations routinely do, just as they routinely publish information that the government does not want revealed. Professional journalists who took comfort from the fact that Assange was not charged with violating the Espionage Act by publishing the State Department cables and Pentagon documents that Manning gave him should think again, since most of the details that the indictment describes as aspects of the conspiracy between Assange and Manning involve actions that reporters consider part of their legitimate work, such as obtaining classified information, secretly communicating with sources, and helping them conceal their identities.

People who get paid for doing that sort of thing are clinging to the hope that their press passes will save them. Assange, writes former CNN correspondent Frida Ghitis, "is not a journalist and therefore not entitled to the protections that the law—and democracy—demand for legitimate journalists."

Washington Post columnist Kathleen Parker notes that Assange's critics view him as "a sociopathic interloper operating under the protection of free speech," an assessment with which she concurs. Real journalists, she says, go through "a lot of worry and process" before they publish embarrassing information that the government wants to keep under wraps. Assange, by contrast, "is not…a journalist, despite his claiming to be, because he isn't accountable to anyone."

This distinction is not just debatable but beside the point. As UCLA law professor and First Amendment scholar Eugene Volokh has shown, the idea that freedom of the press is a privilege enjoyed only by bona fide journalists, however that category is defined, is ahistorical and fundamentally mistaken.

In a 2012 University of Pennsylvania Law Review article, Volokh carefully considered how freedom of the press was understood when the Constitution was written, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when the 14th Amendment (which extended First Amendment limits to the states) was ratified, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in Supreme Court decisions since the 1930s. The evidence is overwhelming that the provision was meant to protect anyone who uses the printed word—and, by extension, media such as TV, radio, and the internet—to communicate with the public.

The implication is clear. If prosecuting publishers for revealing government secrets is deemed to be consistent with the First Amendment, self-appointed guardians of journalistic standards will suffer along with the interlopers they despise.

© Copyright 2019 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (50)