The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

A Right to Smile?

No such right is clearly established when it comes to booking mugshots, says a federal district court.

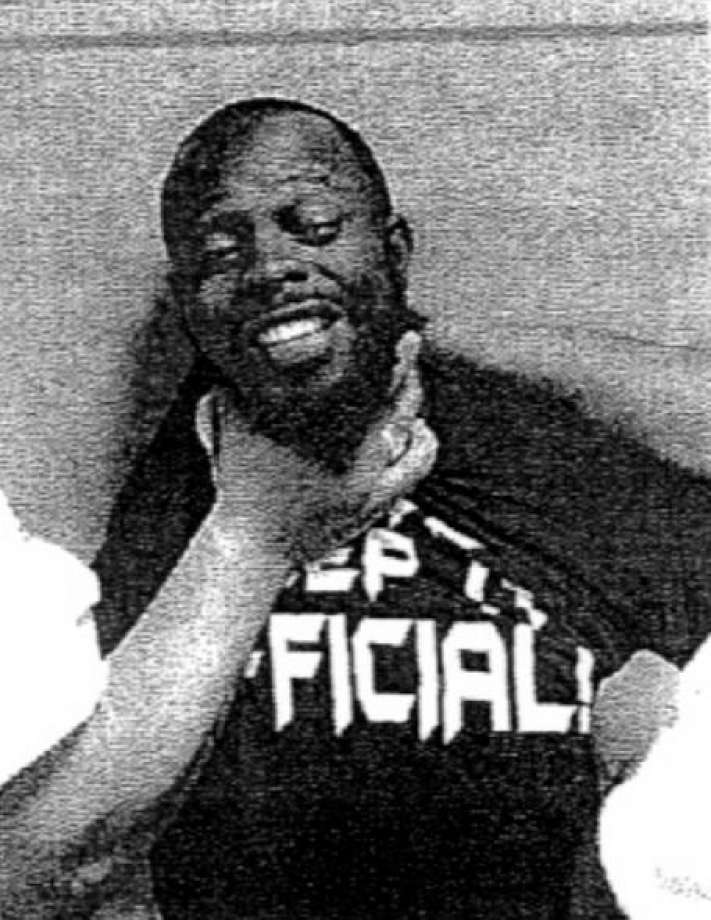

[Photo by Harris County, copied from the Houston Chronicle article.]

From Johnson v. Harris County, decided in July of last year, but only posted to Westlaw yesterday:

As part of the routine booking process [for his DUI arrest], Plaintiff was asked to pose for a jail intake photograph, commonly called a mugshot. While taking approximately ten photographs, Plaintiff smiled for the camera. According to Plaintiff, Phillips ordered him to "Stop smiling!" and asked "What are you smiling for?" Phillips also told Plaintiff, "Take the picture right."

Plaintiff claims that he responded to Phillips by saying, "This is how I always take my pictures. I have a beautiful family at home and I'm a successful business owner and I'm going to beat this case. Why wouldn't I smile, I have nothing to be mad about." …. Phillips [allegedly] told Plaintiff, "Well I'll tell you what! If you don't stop smiling, we gon' to make you stop smiling." At this point, Plaintiff contends that Phillips and Hollis each placed a hand on his neck and held Plaintiff's head before the camera. Plaintiff's official photograph from Harris County Jail shows two officers placing their hands on the front and back of Plaintiff's neck as he continues to smile.

The court rejects plaintiff's First Amendment claim against the officers, on qualified immunity grounds:

Plaintiff contends that Defendant Hollis violated his clearly established right to freedom of expression under the First Amendment. According to Plaintiff, smiling in a jail photograph constitutes protected speech. Plaintiff also asserts that being forced not to smile is humiliating, degrading, and causes him to "look like a criminal" in a publicly available photograph….

Although the First Amendment protects nonverbal and "symbolic speech" in general, a constitutional right for purposes of overcoming qualified immunity [in damages cases against individual government employees] must be defined "with a high degree of particularity." … Thus, it is not sufficient for Plaintiff to assert that people generally have a protected free speech interest in the right to smile. Instead, Plaintiff must show that any reasonable officer in Defendant Hollis's position would have known that the right to smile in a jail photograph was clearly established..

Several courts have recognized that jail photographs and mugshots are imposed on pretrial detainees "in the vulnerable and embarrassing moments immediately after [an individual is] accused, taken into custody, and deprived of most liberties." "A booking photograph is a vivid symbol of criminal accusation, which, when released to the public, intimates, and is often equated with, guilt." The Sixth and Eleventh Circuits have noted the recent trend of websites that post people's mugshots indefinitely and charge money to remove them..

Despite the enduring consequences of jail booking photographs, none of these cases discuss an individual's right to decide his or her facial expression in such a photograph. Instead, the case law only considers whether federal agencies must disclose such photographs under the Freedom of Information Act …. Moreover, none of the cases discuss the possibility that the pretrial detainee may determine the manner or means of the photograph, including the ability to smile.

Based on the prevalence of websites that collect and post jail photographs—including those that charge money to remove them—it would certainly be beneficial if pretrial detainees had the right to smile for the camera…. The question is not, however, whether pretrial detainees should be allowed to smile when they are booked into jail. The question is whether there was a clearly established constitutional right to smile at the time that Plaintiff was booked. See Morgan v. Swanson, 659 F.3d 359, 371–72 (5th Cir. 2011) (nothing that in order to establish a clearly established right, the plaintiff "must be able to point to controlling authority—or a 'robust consensus of persuasive authority'—that defines the contours of the right in question with a high degree of particularity"). Here, Plaintiff has not cited any authority—let alone controlling or robust authority—that clearly establishes a constitutional right to smile in a jail photograph.

Because Plaintiff has not demonstrated a clearly established constitutional right to smile in a jail booking photograph, the doctrine of qualified immunity bars Plaintiff's claim for violations of the First Amendment.

But the plaintiff's excessive force claim could go forward:

Plaintiff asserts a claim against Defendant Hollis for using excessive force in holding his head in place during the intake photograph. Plaintiff also brings a claim against Defendant Quellhorst for failing to intervene to prevent or stop the application of excessive use of force. Defendants Quellhorst and Hollis move for summary judgment on these claims by asserting the defense of qualified immunity..

Because Plaintiff was a pretrial detainee at the time that he alleges excessive use of force, his claim arises under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Kingsley v. Hendrickson, the Supreme Court endorsed four factors to determine whether the intentional use of force "crosse[s]" the "constitutional line":

"(1) The need for the application of force;

"(2) The relationship between the need and the amount of force that was used;

"(3) The extent of injury inflicted; and

"(4) Whether force was applied in a good faith effort to maintain or restore discipline or maliciously and sadistically for the very purpose of causing harm." …

Plaintiff contends that there was no need for any application of force because it was unconstitutional for Defendants to force him to stop smiling and because he was calm, handcuffed, and nonviolent. Defendants assert that Plaintiff was belligerent, argumentative, and highly intoxicated, and that the detention officers had to hold his head in place "because Plaintiff kept walking away from the wall" as the booking photograph was being taken.

At the summary judgment stage, the Court must view all evidence in the light most favorable to Plaintiff. Although Defendants have submitted sworn affidavits to the contrary, Plaintiff testifies that: (1) there was no need for any application of force; (2) the force used against him was grossly excessive; and (3) he experienced severe pain and injury from such force. Plaintiff also points the Court to his official jail intake photograph, which shows him trying to smile as two officers hold the front and back of his neck. Because it is impossible to tell how much force is being applied, the Court assumes Plaintiff's testimony to be true and finds that Plaintiff's affidavit and photograph create a genuine issue of material fact as to whether Defendant Hollis's use of force was objectively unreasonable. Summary judgment is therefore DENIED on Plaintiff's excessive force claim against Defendant Hollis.

It appears that the case was settled three weeks later.

Show Comments (79)