Modern Art Critic Assumes 1939 Painting Is All About Homophobia. It's About Murderous Union Thugs.

Paul Cadmus's Herrin Massacre is "The Painting Our Art Critic Can't Stop Thinking About." If only he'd thought harder.

I was flipping through the latest New York when a headline caught my eye: "The Painting Our Art Critic Can't Stop Thinking About." I also can't stop thinking about it, mostly because it seems to me the critic wildly misrepresented the work.

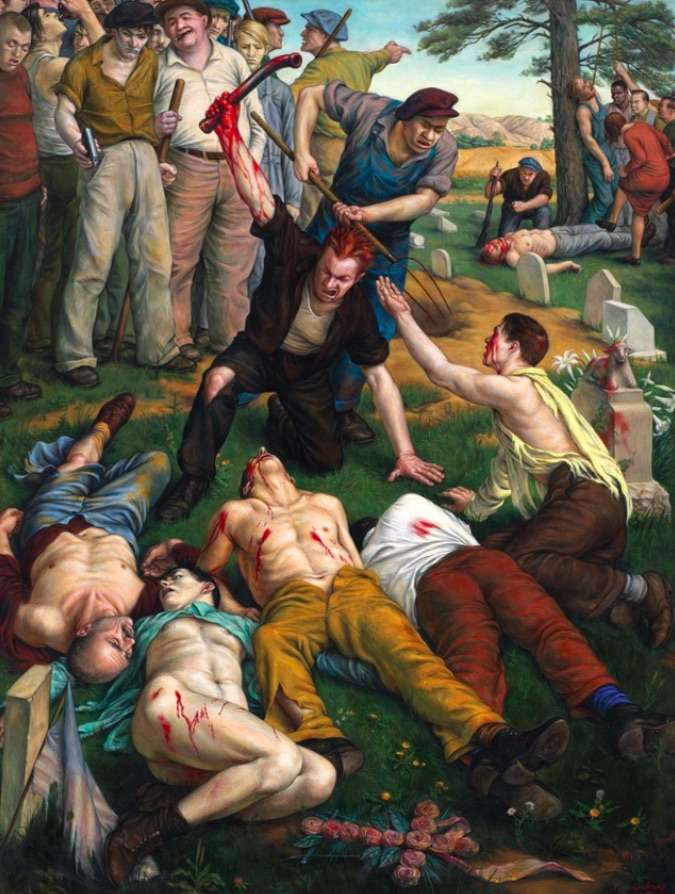

The critic in question is no slouch: Jerry Saltz, a Pulitzer Prize winner. The painting is Paul Cadmus's Herrin Massacre, from 1939. It depicts an angry mob brutally murdering a group of men in a cemetery field. Here it is.

Herrin Massacre attracted Saltz's attention because it was recently featured in "The Young and Evil," a group exhibition "on the homosexual body in America as rendered by gay and bisexual artists from 1929 to 1957." Cadmus, a gay man, paid "obvious sensual attention to the male body," according to Saltz, who repeatedly comments on the themes of sexual violence and intolerance in the work.

"Amid the mob of angry men, one lone, slight, blond boy casts his eyes aside and down," observes Saltz. "We may surmise that he is like those already killed: perhaps homosexual and forced to live in his private closet of fear, shame, guilt, and secrets." In the print edition, this is Saltz's closing thought—one that leaves readers with the distinct impression that this a massacre of gay men.

But as Saltz briefly acknowledges, in a single sentence, the subject of Herrin Massacre is a real historical event: a mob attack that resulted in the deaths of 23 strikebreakers in Herrin, Illinois, in 1922. The Herrin massacre had nothing to do with homophobia; it was a labor dispute that ended with union workers massacring a bunch of people who had been hired to replace them.

On April 1, 1922, the United Mine Workers of America launched a national strike. This was bad news for the Southern Illinois Coal Company, which was massively in debt and negotiated with the union to allow some workers to keep digging. Eventually, negotiations went south, and the company's owners brought in outside help. Some 50 workers from Chicago arrived at the coal mine, unaware that they were crossing picket lines. On June 21, union workers attacked the strikebreakers, who surrendered after a skirmish. A mob then marched the captives away from the mine and massacred at least 18 of them. None of the killers faced justice; 90 percent of the county's workforce belonged to the union, and sympathetic juries acquitted the workers.

This is a fascinating chapter in the history of American labor, and one that we don't often revisit. For modern progressives, unions are generally the good guys—an important branch in the tree of intersectionality. (Though they occasionally cause trouble. Trump attracted some union support.) Cadmus reminds us that they could be thuggish; in his painting, he portrays the unionists as ugly, sullen, drunken, murderous brutes.

It's not that the painting is devoid of gay content—the victims are shirtless and ripped—but to portray it as an obvious metaphor for anti-gay violence is to insert modern grievances where they don't belong. This is "The Painting Our Art Critic Can't Stop Thinking About," and yet it seems he didn't think very hard.

For anyone who suspects I'm being too harsh, note that Saltz laments in his review that "Corporate-American Life," the magazine that commissioned the painting, "never reproduced the picture." Readers are left with the implication that the painting was too risqué, too transgressive for the heteronormative rubes at Life.

In reality, Life declined to publish the painting "most likely because the magazine did not wish to offend organized labor just as the nation was gearing up for war production," according to the Columbus Museum of Art.

Show Comments (121)