Howard Schultz's Prospects: Ballot Access Promising, Other Fundamentals Not So Much

The Starbucks magnate is rich and early enough to buy his way onto ballots, but it's hard for a relative unknown to beat the third-party boomerang effect in a time of centrism-hating polarization.

Six weeks ago, I wrote in this space about "The Fantasy of a 2020 Independent Centrist," arguing that a "polarized electorate's sharp disdain for squishy centrists," combined with the "bureaucratic roadblocks erected by the Democratic and Republican parties," would significantly ramp up the degree of difficulty for any pox-on-both-houses run.

So now that we have our first major volunteer for the job, how does that analysis apply?

Certainly the hostility toward squishy centrist Howard Schultz, who twice served as CEO of Starbucks, almost immediately reached firehose-level intensity, as Elizabeth Nolan Brown and Nick Gillespie have documented. The high-turnout, Trump-centric 2018 midterms were brutal enough for non-major-party candidates, and the president's name wasn't on any ballots. If someone with as much local name recognition and relevant job experience as former Gov. Gary Johnson in New Mexico can barely get half the vote of a no-name Republican in a presidential off-year, what chance does a no-name independent amateur have when the anti-Trump electorate will be more motivated than Fantastic Mr. Fox at a pancake breakfast?

It's actually on the structural-impediments side that things start to look up for Schultz. "Ballot access for such a ticket is not nearly as bad a problem as it has been in the past," Ballot Access News editor Richard Winger told me last month. "Since the 2016 election, ballot access for president in the two worst states, North Carolina and Oklahoma, has become much easier. And in 2016 it became much easier in Georgia." Ongoing litigation could also improve the rules in Texas, Florida, and California.

Sure, states run by Democrats may try to erect new obstacles over the coming months, but such shenanigans could face the kind of pushback not seen for more than two decades—a highly motivated billionaire willing to throw his own money at the problem.

"Running for president should not be undertaken without intense preparation," Schultz wrote in yesterday's USA Today, sounding like someone who has been doing just that. "I promise that I will not seek the presidency unless I believe it is possible to win, and for me to govern well. Should I run, I will be on the ballot in all 50 states."

According to the Washington Post, the former Starbucks CEO has indeed been laying the groundwork prior to his 60 Minutes splash, and has expressed willingness "to spend $300 million to $500 million of his own wealth" on the effort. "Before announcing his presidential ambitions this week," the Post reported, "Schultz secretly undertook a months-long effort to prepare an independent presidential campaign against the nation's two-party political system, deploying more than six national polls and laying the groundwork for paid advertising that could debut in the next two months."

One other advantage Schultz has besides money, is time—he's at least one full year ahead of where quadrennial trial ballooner (and 2019 Schultz-baiter) Michael Bloomberg was in 2016, and miles ahead of the stillborn June 2016 candidacy of David French, or the August 2016 Evan McMullin scramble that resulted in the #NeverTrump candidate getting on just 11 state ballots.

So that, plus the wide open fiscal/economic space between Trumpism and the left-lurching Democratic Party, comprises the good news for Schultz. The bad news? Just about everything else.

Donald Trump may have illustrated that past patterns do not determine contemporary presidential success, but that doesn't make history irrelevant. And when you look at independent/third-party runs from days of yore, as well as the depressing realities of contemporary politics, Schultz 2020 comes up against at least four major impediments.

1) Name recognition. Since the end of World War II, independent and third-party candidates for president have received more than 2 percent of the popular vote eight times. All were considerably more famous than Howard Schultz.

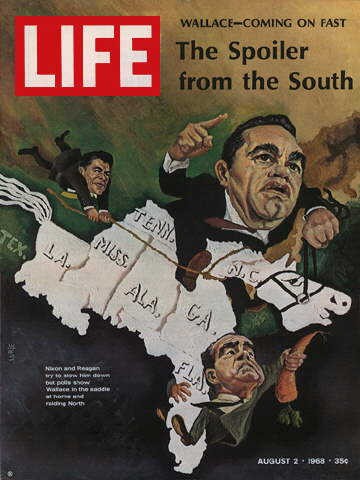

Ross Perot (18.9 percent in 1992, 8.4 percent in 1996) was trebly famous by the time he got into politics—for starting a wildly successful data processing business, organizing the dramatic hostage-rescue operation of his employees in revolutionary Iran, and being the most influential private-sector activist for American POWs and M.I.A.s in Vietnam. George Wallace (13.53 percent, 1968) was arguably the most infamous segregationist governor in the South during the civil rights era. Like Wallace, Strom Thurmond (2.41 percent, 1948) was the face of states' rights opposition to desegregation, and had already been a governor, circuit court judge, state senator, and war hero before running for president. Gary Johnson (3.28 percent, 2016) was a two-time governor and second-time presidential candidate. Ralph Nader (2.74 percent, 2000) was and is the single most famous consumer advocate in the country. And Henry Wallace (2.37 percent, 1948) had been vice president three years before.

The one comparatively successful third-party candidate who comes anywhere near Schultz's anonymity is John Anderson (6.61 percent, 1980). But Anderson was a 10-term congressman, the third-ranked Republican in the House, and a headline-generating apostate on Watergate, Vietnam, and the Equal Rights Amendment, and he had just finished third in the GOP presidential primaries.

2) The third-party boomerang effect. Close elections, like the one we had in 2016, tend to scare voters away from third-party and independent candidates the next time around. The 2000 election saw 3.75 percent of voters select non-major candidates; in 2004 that number collapsed to an even 1 percent. The 1968 Richard Nixon popular-vote squeaker over Hubert Humphrey included 13.86 percent going rogue; in 1972 that plummeted to 1.81 percent. Even 1960's miniscule third-party percentage of 0.33 nearly halved in 1964, to 0.18.

The 2016 third-party/independent haul was 5.73 percent, the highest in two decades.

Not only do hotly contested elections bring voters back home to major parties, but spike years in third-party voting tend to be followed by nosedives. The Strom Thurmond/Henry Wallace election of 1948 (5.38 percent for non-majors overall) was followed by 1952's 0.5 percent. The John Anderson–led 8.14 percent in 1980 dwindled to 0.71 percent in 1984. The Perotist peak of 19.52 percent in 1992 was nearly halved in 1996 with the feisty Texas still on the ballot: 10.04 percent.

3) The centrist sinkhole. Schultz is selling himself as a sensible centrist, above the distasteful fray of polarized Washington. Ask Jeff Flake how popular that is.

Or even Bill Weld. The 2016 Libertarian Party vice presidential nominee and possible 2020 presidential contender now repudiates his centrist, very Schultz-sounding marketing pitch of three years ago with Gary Johnson. "'Well, you know, we're socially welcoming and we're fiscally responsible, and one of the other two parties is not socially welcoming and the other one is not fiscally responsible, so we've got a six-lane highway right up the middle!'" Weld recalled last October. "I think that might have been a fundamental error….I'm suggesting that we should never say, 'You have to vote for us because we're in the middle.'"

4) Fiscal freebasing. There is no demonstrable electoral constraint on major-party presidential candidates campaigning as if budgetary numbers ever have to add up. Donald Trump laughed that rhetorical tradition right out of the national GOP, and all the juice on the Democratic side is coming from Team Bernie.

Howard Schultz—just like whoever the Libertarian nominee will be—is bucking that trend, and I for one wish all of them success in reanimating the corpse of fiscal responsibility in our national politics. But we've come so far from the debt-limit/budget-sequestration days of 2011–2013, let alone the "net spending cut" and entitlement reform promised by incoming president Barack Obama 10 years ago, that even imagining a successful politics based on fiscal sanity requires effort.

Which makes one tidbit buried in the Washington Post article all the more interesting: Schultz's internal polls reportedly show him doing best when pitted against a more progressive Democrat, rather than, say, Joe Biden. I suspect the single biggest role Schultz may play in this election is not on his own candidacy, but on how Democratic voters—so desperate to find someone who can smite down Trump—select their own nominee.

Show Comments (72)