Dropouts Built America

When the going gets tough, the tough start something better.

We don't know the location of the first European settlement in the land that would become the United States.

We know that Spanish colonists founded it in 1526. We know that they called it San Miguel de Guadalupe. We're pretty confident that the site was in either what is now South Carolina or what is now Georgia. But we don't know the exact location, because the people who didn't die there cleared out in less than a year. Disease and hunger ripped through the town, the leaders took to fighting among themselves, there was a clash with the local Indians, and the settlement's slaves revolted. Hundreds of colonists were dead within a few months, and the remainder fled to Hispaniola.

Well, some of the remainder fled to Hispaniola. The rebel slaves disappeared into the wilderness, where they are believed to have settled among the Indians. The formal colony failed; the underclass stuck around. The first arrivals from the Old World to stay here permanently were mutineers seizing that most essential of freedoms: the right to walk away.

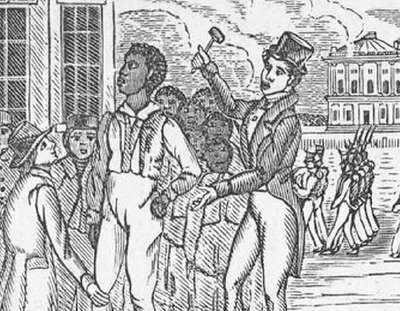

The liberated chattel of San Miguel de Guadalupe were not the only Americans in bondage who escaped either to assimilate into an Indian community or to create an independent colony of their own. The Western Hemisphere was dotted with settlements known as maroon societies, where former slaves, their descendants, and anyone else who joined them lived in one configuration or another. Some simply tried to avoid the world they'd escaped, while others raided or traded with outsiders. Some were relatively autocratic, with a military leader, a probationary period of servitude, and a strict code of secrecy; others were more loose. Some lasted a long time—Palmares, a federation of thousands of maroons in the mountains of Brazil, persisted for nearly a century—and some were fleeting.

For most maroon communities, anything we say about how they were organized or how long they existed has to rest on a lot of conjecture. Open A Desolate Place for a Defiant People, the American University archaeologist Daniel Sayers' 2014 book about the maroons who lived in the Great Dismal Swamp of North Carolina and Virginia, and the caveats leap from the page: "I suspect that…" "We can be reasonably certain that…" "It is also quite possible…" "It would not be particularly outlandish to also suggest…"

The Great Dismal Swamp was what the Yale political scientist James C. Scott calls a "nonstate space": a region, as he puts it in 2009's The Art of Not Being Governed, where "owing largely to geographical obstacles, the state has particular difficulty in establishing and maintaining its authority." Those obstacles can take different forms in different parts of the world—Scott mentions "swamps, marshes, mangrove coasts, deserts, volcanic margins, and even the open sea"—but they all offer the advantage of greater autonomy.

Of course, those obstacles could make life difficult for the maroons as well as their pursuers. They call the great swamp dismal for a reason.

Geographic barriers weren't the only potential protection for walkaways. Political rivalries could be quite helpful. In the Caribbean, the English deliberately allied themselves with maroon colonies, joining them in attacking the Spanish. Further north, the situation was soon reversed: Spanish Florida offered a haven to slaves fleeing English South Carolina. When another set of British colonists established Georgia, the government there outlawed slavery but continued to return runaway slaves to their masters—a combination that the English hoped would help the colony serve as a buffer zone between South Carolina's slave society and the relative freedom of Florida. (This didn't placate those Georgians who wanted to own other human beings. Eventually the would-be masters prevailed, and the colony ended its slavery ban in 1751.)

It wasn't just African slaves who learned the power of walking away. Six decades after the collapse of the Spanish settlement at San Miguel de Guadalupe, the first English settlement in the future United States—on Roanoke Island, in what is now North Carolina—simply disappeared. Historians debate what happened to it, but a popular and persuasive theory holds that the missing colonists left to live among the natives. After the first permanent English settlement, at Jamestown in Virginia, was established in 1607, it wasn't long before its laborers were slipping off to trade with the Indians and sometimes to join them outright. When one of the colony's officials, John Smith, was taken captive, a leader of the Powhatan confederation offered him a prominent position in their society if he would betray the Englishmen back at the fort. He "would be given ample land to set himself up as an important Indian, enough to support not only himself but several wives as well," Joseph Kelly writes in Marooned (Bloomsbury Publishing), his engrossing new history of Jamestown.

One of the original Virginia colonists, Ralph Hamor, reported that the most powerful Powhatan figure—Wahunsonacock, who the English often called Chief Powhatan—was the son of an escaped slave from the West Indies. Kelly notes that this has never been confirmed but also that it has never been contradicted. It is possible, in other words, that the most influential indigenous leader that the Jamestown colonists encountered was a second-generation American himself.

In any event, Smith didn't accept the invitation to turn Indian, and eventually he returned to Jamestown and took command of the colony. But while he and Wahunsonacock reigned over the Chesapeake, a hybrid English-Indian culture began to emerge—the sort of frontier interzone that the Stanford historian Richard White calls a "middle ground." And in that social environment, as Smith tightened his grip over the English settlers' lives, many of his men decided that the Indian world looked more appealing and disappeared deeper into the interior.

As the decades passed and a privileged planter aristocracy coalesced, one place began to draw dissatisfied Virginians ranging from former indentured servants to Quakers: a loosely self-organized society that emerged in the area south of the Great Dismal Swamp and north of Albemarle Sound, not so far from the "lost" colony of Roanoke. Up north, people chafing at Puritan rule in Massachusetts—or pushed out for challenging it—found their own escape hatches. The best-known of those, launched by the exiled minister Roger Williams, was the place eventually known as Rhode Island, where religious freedom was the law of the land. And if even Williams' rule was too restrictive for you, you might follow the anti-authoritarian dissident Samuel Gorton and his co-conspirators to the town of Shawomet, now known as Warwick. There they purchased some land from the local Indians and established a settlement that, until Rhode Island absorbed it in 1648, had no formal government at all.

Not unless you count the government in Massachusetts, which tried vigorously to seize Shawomet for itself. Dissidents may claim the right to exit, but the authorities aren't always willing to grant it.

That right to exit an existing society looked particularly appealing in South Carolina. In 1670, nearly a century and a half after the collapse of the colony at San Miguel de Guadalupe, a group of British noblemen established a permanent Province of Carolina. Its founders imagined a well-planned landscape whose government carefully balanced different social groups' competing interests; their blueprints were directly influenced by a utopian text, James Harrington's The Commonwealth of Oceana. Like many utopian experiments, this one proved deeply dystopian in practice.

Carolina—particularly the southern portion, which eventually was split into a separate colony—was, in the words of historian Timothy James Lockley, the mainland colony "most sharply defined by slavery." Many of the aristocrats who invested in Carolina were also investors in the Royal African Company, which was heavily involved in the slave trade; certain synergies presented themselves. By 1720, about 65 percent of the population was enslaved. The resulting caste system arguably had more in common with the plantation economies of the Caribbean than it did with England's other mainland colonies. Little wonder that its slaves would soon be fleeing to Florida—or if that trip was too difficult, into the Carolina swamps.

In a historical irony, that egregiously illiberal society has come to be associated with one of the forefathers of classical liberalism. The English philosopher John Locke helped draft the colony's first governing document, known as the Fundamental Constitutions of the Carolinas. Unpopular with many colonists, it was discarded quickly, but that doesn't get it off the hook; it didn't exactly reject the emerging system of servitude. "Every freeman of Carolina," the constitution declared, "shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves."

That document is therefore usually Exhibit A when people try to link the Lockean liberal tradition to slavery and similar forms of oppression. (Exhibit B is the stock that Locke briefly owned in the Royal African Company.) Some critics simply accuse Locke of hypocritically failing to live by his principles, but others draw more sweeping conclusions. "If Locke is viewed, correctly, as an advocate of expropriation and enslavement, what are the implications for classical liberalism and libertarianism?" the socialist outlet Jacobin asked in 2015. "The most important is that there is no justification for treating property rights as fundamental human rights, on par with personal liberty and freedom of speech."

But that view of Locke has come under sharp scholarly challenge. In 2017, historian Holly Brewer of the University of Maryland published a paper in the American Historical Review called "Slavery, Sovereignty, and 'Inheritable Blood': Reconsidering John Locke and the Origins of American Slavery." Forty-one pages long and built on nearly a decade's worth of research, it argues that John Locke "wrote Carolina's constitution as a lawyer writes a will"—as a contractor, not an architect—and that key elements of the plan, including the presence of slavery, were in place before he came aboard. More importantly, Brewer argues that Locke's liberalism developed in large part as a reaction to the system of absolutism, slavery, and hereditary status that he witnessed up close while the Stuart dynasty ruled England.

Locke and his mentor—Anthony Ashley Cooper, the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury—worked with the Stuarts from 1669 to 1674, a period that included the creation of Carolina. But as the Whig opposition emerged in the 1670s, both Locke and Cooper became involved with it, publicly condemning the king in 1675. In opposition, Brewer recounts, "Locke developed a philosophical argument against both hereditary hierarchy and property in people." After the revolution of 1688, which Locke justified in his Two Treatises of Government, the new king "appointed Locke and his allies to oversee colonial policy to fulfill the promises of the Glorious Revolution. These men then tried to undo Stuart imperial policies pertaining to large estates, bound labor, and oligarchy."

Brewer assembles strong evidence that Locke wrote "Some of the Cheif Greivances of the present Constitution of Virginia, With an Essay towards the Remedies thereof," a document that called, with partial success, for liberal reforms in the New World. Most notably, it attacked Virginia's perverse system of property ownership, in which colonists could acquire more land by importing more bound "servants."

In Brewer's balanced account, "Locke's early involvement with the Stuart slave program gave him the incentive and knowledge to challenge it. While translating principles into laws is a messy business, full of compromise, as an old man he helped undo some of the wrongs he had helped to create.…Some reforms were later reversed, and others incompletely implemented, but we should not judge the revolution by the reaction." Locke's liberalism was inconsistent in many ways, but Brewer's most important point isn't about Locke himself. It's about the revolution he helped build and its relationship to the slave economy that had been developing. "Legally and ideologically," she explains, "slavery was anchored in hierarchical and feudal principles that connected property in land to property in people, principles that were bent to new forms in England and its empire by Stuart kings.…Liberalism emerged in reaction to such principles—and not simply in the writings of Locke, though his writings provide a convenient window into that conflict."

Brewer is right: The liberal reaction did not emerge only in the writings of Locke. Indeed, it did not emerge only in writing, period. When people on the receiving end of repression encountered opportunities for mutiny or escape—for forming a new social compact on the fly—they sometimes proved quite capable of constructing the rough essentials of liberty and self-government on their own. Out beyond the edge of the empire, freedom beckoned.

That's a central theme of Marooned, whose title is a pun: Kelly's book has a lot to say about maroons, but it also discusses a group of people who were marooned in the sense of being stranded on a distant island. Specifically, it devotes a lot of attention to the Sea Venture, one of the boats sent to Jamestown as part of the third supply mission of 1609. Caught in a hurricane, it was shipwrecked on Bermuda and believed lost until 1610, when the survivors finished building two new ships and sailed them to Virginia.

The wreck left an indelible mark on English literature, since it inspired William Shakespeare's The Tempest. Kelly argues that it left a mark on American political history as well. Stuck on an island with Sir Thomas Gates, Virginia's newly appointed governor, many of the passengers came to resent his absolute authority and the system of forced labor and garrison discipline that he imposed. They also came to realize that they were almost certainly better off in plentiful Bermuda than in Virginia, where they would have to keep toiling under the same tyranny. Resentment bred revolt, conspiracy, and attempts to escape into the island wilderness.

One of the shipwrecked men, a former farmer named Stephen Hopkins, vocally denounced the absolutist order and argued that the ship's passengers should not be bound to it. As one Gates loyalist paraphrased it, Hopkins argued that the Virginia Company's "authority ceased when the wreck was committed, and, with it, they were all then freed from the government of any man." Bermuda was a place of abundance, and a settler marooned there was bound only "to provide for himself and his own family"; the passengers need not submit to anyone's orders except to the extent that "it so pleased themselves."

A subsequent rebel, Henry Paine, was blunter: Gov. Gates, he announced, "can kiss my arse."

Paine was executed for those words. Hopkins was nearly executed, but his life was ultimately spared. He traveled to America, then apparently back to Europe, and then, most likely, back to America again: In 1620, a man named Stephen Hopkins—probably the same one—was among the passengers headed for Plymouth on the Mayflower. Kelly suggests, speculatively but enticingly, that he played a key role in the birth of America's most famous colonial constitution.

As the Pilgrim leader William Bradford later recalled it, some "strangers"—that is, non-Pilgrims—began to make "discontented & mutinous speeches" on the ship. The Mayflower, they noted, was landing in a place outside the jurisdiction of the Virginia Company. Therefore, the strangers argued, "none had the power to comand them"; they were free in that state of nature to "use their owne libertie," and they need not submit to a government that had not acquired their consent. The result was the Mayflower Compact, a document establishing that this consent had been given. And the argument that led there, Kelly notes, "sounds remarkably like Stephen Hopkins's political discourse in Bermuda."

Again and again the process repeated itself. That first settlement in what is now Massachusetts may have been influenced by the attempt to go marooning in Bermuda; when Massachusetts society grew too repressive, its dissidents lit out for Indian lands or formed new communities of their own. Not all of those new communities lasted as long as Rhode Island did. There was, for example, the short-lived outpost of Merrymount, whose defiant residents ignored a host of Puritan rules and traded freely with the natives.

Kelly doesn't mention it, but Hopkins was part of the expedition that seized Merrymount and disarmed its leaders. Evidently, Locke wasn't the only person whose liberalism had limits. But the idea of liberty is larger than any one spokesperson anyway.

America was born, we're often told, as a place where the dissidents of the Old World could create freer spaces for themselves. There is truth to that, but the settlement of the continent was caught up with a lot of uglier factors too: with slavery and empire, with feudal status and monopoly privilege. What undermined those evils—what made America a place where liberty as well as power could take root—was the fact that it wasn't just the exiles of the Old World who set up communities here. The outcasts of the New World sought and sometimes seized the right to drop out and build their own Americas too. When Europeans arrived intending to form new societies, they soon found that some of their dissatisfied subjects were happy to break off and form yet more new societies of their own—or just to move to a more appealing-looking society next door, be it Rhode Island or the Algonquins.

Carolina was a startup society, complete with both profit-seeking proprietors and utopian ideals; the founders even had John Locke on hand to help write their constitution. But for a lot of the people who lived there, for a long stretch of its history, the only hope of happiness lay in breaking the law, asserting their own right of exit, and perhaps forming a more consensual startup society of their own. In re-enacting the rebellion of those slaves in San Miguel de Guadalupe. In walking away.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Dropouts Built America."

Show Comments (27)