Resources Are Almost 5 Times as Abundant as They Were in 1980

New Simon Abundance Index elegantly refutes primitive zero-sum intuitions with respect to population and resource availability trends.

Humanity is enjoying a world of increasingly cheap and ever more abundant mineral, argicultural, forestry and energy resources reports a brilliant new study, the Simon Abundance Index. This analysis by Marian Tupy,* editor of Human Progress at the Cato Institute, and Professor Gale Pooley from Brigham Young University – Hawaii uses data on 50 different commodities to track their price trajectories over the past 37 years from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. They find in real price terms their basket of commodities decreased by an average of 36.3 percent between 1980 and 2017.

That's great, but their breakthrough insight is that, since 1980, global real hourly income rate per capita has grown by more than 80 percent, which means that the commodities that took 60 minutes of work to buy in 1980 now take only 21 minutes of labor to buy in 2017. As a result, the "time-price" of their basket of commodities has fallen by 64.7 percent.

Tupy and Pooley also devise a price elasticity of population (PEP) measure that finds that resource abundance increases faster than population does. In economics, they explain, elasticity is a measure of a variable's sensitivity to a change in another variable. They report:

Between 1980 and 2017, the time-price of our basket of commodities declined by 64.7 percent. Over the same time period, the world's population increased from 4.46 billion to 7.55 billion. That's a 69.3 percent increase. The PEP indicates that the time-price of our basket of commodities declined by 0.934 percent for every 1 percent increase in population.

[P]eople often assume that population growth leads to resource depletion. We found the opposite. Over the past 37 years, every additional human being born on our planet appears to have made resources proportionately more plentiful for the rest of us.

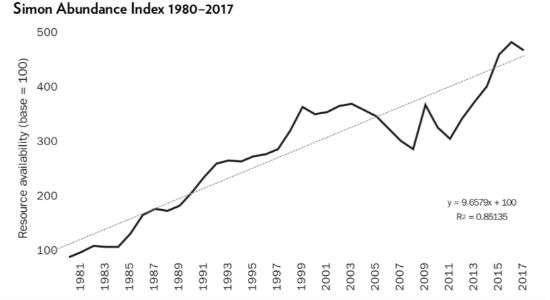

Tupy and Pooley combine their findings with regard to time-price and PEP trends to derive the Simon Abundance Index (SAI). The index is named in honor of University of Maryland economist Julian Simon. Simon famously bet Stanford University population bomber Paul Ehrlich and his colleagues that the real prices of a basket of commodities chosen by Ehrlich priced $1,000 would decline between 1980 and 1990. In October 1990, Ehrlich mailed Simon a check for $576.07, meaning that the price of the commodities had fallen by more than 50 percent.

The new SAI, explain Tupy and Pooley, represents the ratio of the change in population over the change in the time-price, times 100, with the base year at 1980 and a base value of 100. They report that "between 1980 and 2017, resource availability increased at a compounded annual growth rate of 4.32 percent. That means that the Earth was 379.6 percent more abundant in 2017 than it was in 1980."

They also report that the SAI rose to 479.6 in 2018, meaning the Earth was nearly five times more plentiful with respect to the 50 commodities they track than it it was when Ehrlich and Simon laid their famous wager. What about the future? Tupy and Pooley calculate if current trends continue that "our planet will be 83 percent more abundant in 2054 than it was in 2017."

"The world is a closed system in the way that a piano is a closed system. The instrument has only 88 notes, but those notes can be played in a nearly infinite variety of ways. The same applies to our planet," write the authors. "The Earth's atoms may be fixed, but the possible combinations of those atoms are infinite. What matters, then, is not the physical limits of our planet, but human freedom to experiment and reimagine the use of resources that we have."

The SAI devised by Tupy and Pooley elegantly refutes the primitive zero-sum intuitions peddled by the likes of Ehrlich and his acolytes that afflict so much of popular and policy discourse with respect to population and resource availability trends.

*Disclosure: Marian Tupy and I are working together on book that tracks and explains nearly 100 global population, income, commodity, and environmental trends.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

So far, all predictions of doom have been wrong. No reason to think that will change anytime soon.

Unless we let all those immigrants in!

My favorite is you think that's a joke, but Simon noted at least three things are needed for economic prosperity: freedom, rule of law, and individual rights, especially property rights.

Immigrants, by and large, do NOT believe in any of those things. Whites are the only group in history, and even then just a sub-population of whites, ever believed in these things so much as to literally fight for them, codify them in law, and defend them with blood.

Lord help us. No most of these resources - with the possible exception of 'renewables' - have not become 'more abundant'. They are just not included as a separate factor in neoclassical economics so economics cannot price the value of non-extracted resources (which is an option value) and so can only price the extracted value. Since technology will always tend to drive extraction costs down over time, it merely APPEARS that those resources are more abundant.

Lord save us from quibblers.

And neo-malthusians.

How can something be abundant if you don't have it or can't reach it? In theory there could be asteroids made of solid gold. Does that mean gold is abundant? No. Because we can't capture the gold and bring it to Earth. The mere existence of something doesn't make it abundant. You need access to it as well.

J: As I quoted in my 2000 article, The Law of Increasing Returns, this year's economics co-Nobelist Paul Romer:

"Every generation has perceived the limits to growth that finite resources and undesirable side effects would pose if no new recipes or ideas were discovered. And every generation has underestimated the potential for finding new recipes and ideas. We consistently fail to grasp how many ideas remain to be discovered. The difficulty is the same one we have with compounding. Possibilities do not add up. They multiply."

This, I explain, it should be noted, is the mirror image of Malthus' argument about exponential growth. Here, however, ideas grow much faster than population.

That is exactly what the new SAI demonstrates.

That is merely an argument that we underestimate technology changes. I agree.

It doesn't address the argument about whether the resource itself is abundant or being made more so because of that tech/idea.

Let me use one example - the dodo. My guess is that once we discovered it, it became cheaper and cheaper to turn it into meat. It didn't become more expensive as it actually got scarcer - which is what one expects when a resource/factor is included in economic models (eg labor and capital).

It got cheaper and cheaper - until overnight the cost went to infinity because the resource stopped pining for the fjords and became demised. That's the sort of pricing curve one would expect when the resource itself isn't even included in an economic model. Can see a similar thing with Atlantic cod fishing. From 1945 to 1968 or so, the catch went from 300k tons to 1800k tons. Cool technology like sonar and better boats and stronger nets. But the technology didn't make the resource more abundant. It collapsed from that 1800k tons back to 400k tons from 68-71 - and then collapsed to 18k tons by 1992. The area was closed in 1992 - but the fish hasn't recovered at all.

The technology simply allowed us to extract more - at a lower cost - until the thing itself ceased to be.

J: Overfishing is a problem and it is already being solved the way overhunting was - farming. Deer shortages relative to meat demand led to more cows and sheep. Fish shortages relative to demand leads to more aquaculture. The relevant resource is not wild cod, but edible fish.

Problem is that fish farming doesn't actually solve overfishing. We overfish - then put that species on a farm - then overfish an as yet underfished fish to feed the farmed fish in the form of fish meal. Until (see jack mackerel) that species is on the verge of collapse as well. Maybe Soylent Tech has some economic alternatives.

The relevant resource is not wild cod, but edible fish.

And this redefinition of the resource doesn't help either. It just means that as long as we have domesticated chicken, then every other bird species can be driven to extinction. 'Food' is not actually a resource-resource. It is what we call the resource when it used to keep labor (which IS in our economic model) alive from today to tomorrow. We could just as easily call it 'protein' or 'calories' - and I agree that that doesn't work on some Malthusian basis. But I'm trying to include resources in economics - not turn all resources into food in order to satisfy a Malthusian assumption.

And the biggest resource issue re that redefinition of resources is not 'food' but 'energy'. Energy itself won't run out. But as long as what are we consuming is millions of years of previously stored solar-source in the form of fossil fuels where that energy remaining in storage is not priced, then we are not going to transition to a currently received solar-source system.

Even though that annually received solar-source is (roughly) 6000x greater than all annual energy consumption and 2000x greater than projected energy consumption in 2100 - and there are apparently some side-effects of burning that stored energy that we don't even want to understand. IOW - we aren't even going to rise to the technological challenge that apparently solves everything - because we deem the effort itself economically irrelevant.

"We overfish - then put that species on a farm - then overfish an as yet underfished fish to feed the farmed fish in the form of fish meal."

Nope. There's no profit in consuming all fish in your fishery. What type of person really thinks a fish farmer will sell all his fish this year to increase this year's profit, knowing next year's will be $0?

"And this redefinition of the resource doesn't help either."

This is not a redefinition. The availability of a resource 100% depends on alternatives. Again, all you've done is shown how little you understand basic economics.

"It just means that as long as we have domesticated chicken, then every other bird species can be driven to extinction."

False. The rest of your comment is incoherence based on your erroneous understanding.

"That is merely an argument that we underestimate technology changes"

Technology makes resources more widely available, i.e., abundant.

"It doesn't address the argument about whether the resource itself is abundant or being made more so because of that tech/idea."

False.

"Let me use one example - the dodo."

The dodo wasn't a resource.

"My guess is that once we discovered it, it became cheaper and cheaper to turn it into meat. It didn't become more expensive as it actually got scarcer."

You'd guess wrong, as you make abundantly clear you don't understand what supply and demand is. Guess what happens when supply decreases. All the dodo makes clear is that it was not a resource.

The problems with hunting and fishing you note are classic tragedies of the commons, where not only property rights not well defined, but activists take active steps to prevent well defined property rights.

"The technology simply allowed us to extract more - at a lower cost - until the thing itself ceased to be."

The most ridiculous part of this statement, other than it being false, is you don't even consider technology allows less usage of a particular resource. An easy example is the aluminum can. The amount of aluminum needed today is less than the amount needed a few decades ago, despite more cans being created today than a few decades ago. You know how? Less aluminum, a LOT less aluminum, per can.

When they build the Washington Monument they topped it with aluminum. Why? Because at the time that was the rarest metal. That's because it doesn't exist in a metallic form in nature, and it takes shitloads of energy to turn it's natural state into something useful. We can do that now relatively cheaply, so aluminum is now abundant. Would it be accurate to say it was abundant when they make the monument? I don't think so. It's human ingenuity that makes something abundant, not its mere existence.

Dude, perfectly said.

Why?

Aliens.

^

Metals are not 'consumed'. They are mostly just refined. So over time, the resource itself is not going to disappear. We will just find more of that resource via recycling of the old resource - assuming that THAT technology/pricing advances roughly in line with the primary extractive tech/pricing.

The issue arises when we are actually consuming that resource.

There is no rational way to solve for the equation you have put forward. Resources are so prevalent in this universe that they approach infinity. That is the whole point of this article. If by some stretch of the imagination, we were able to extract every ounce of those resources from earth's crust and mantle, there thousands of times more than that in the celestial bodies orbiting our sun, and billions of times that in our galaxy alone. Those resources are ours if we just develop the technology to get them at a reasonable cost. That trend is what this study is pointing out.

"Resources are so prevalent in this universe that they approach infinity. That is the whole point of this article."

That is definitely NOT the point of the article.

Caf? Hayek likes to note that"natural resources" are no such thing; they are developed by humans who find them and turn them into resources.

There are no natural resources

Cafe Hayek, lWhere Orders Emerge," is a terrific site.

One of many that outshine this one as bastions of "free minds and free markets."

And, unlike this site, it is quite functional, even on mobile devices.

And, unlike this site, it is quite functional, even on mobile devices.

Doesn't Reason have an app? This doesn't excuse them neglecting the mobile UX experience, but I have to wonder if they're trying to tacitly encourage users to use that instead of the website.

Thank you for the article. (Though the last paragraph will arguably be controversial here.) The collective pants-shitting over the potential pernicious implications of climate change ostensibly ignores the ingenuity and resourcefulness (ayy) of the human mind.

I have one point of contention, however, and that is this: the fall in the real prices of industrial commodities signals a colossal increase in their supply. This could be true but not necessarily. Couldn't these decreases in prices also implicate the reduction of difficulty and cost of the overall process?

No! Supply and demand -- if the price drops, either the demand has decreased or the supply has increased.

If they cost more to produce, prices would go up, they have to, and that will reduce demand but encourage an increase in supply, and the increased supply will bring the price back down. Or people will find an alternative supply, old product demand will drop, old product price will drop.

Yes, that last paragraph would set all the xenophobes screaming. While people are just another resource to fill supply in that regard, they are also another demand for other resources. Since people (including immigrants) produce more than they consume (or we would be shrinking GDP and growing poorer as a society), we are always better off with immigrants, legal or not.

Nice, Reason kickin' it old school today. Nice relief from the latest campus outrage.

That whole scene has gotten lame and tired man.

"Student offended by white paper'. Blah, blah.

Resources may be almost 5 times as abundant as they were in 1980 but demand is still high for hair shirts, sackcloth and ashes if contributions to environmental doomsaying groups are any indication.

The fact that Paul Ehrlich still has an audience as anything other than as comedy is amazing. He had a prominent spot on one of the NPR commentary programs and a favorable mention on the BBC just within the last couple of weeks.

I'm not how you calculated the 21 minute figure, but when I divide 60 minutes by 1.8 (i.e., 180%), I get about 33 minutes. This also changes the time price reduction from 64.7 percent to about 44 percent.