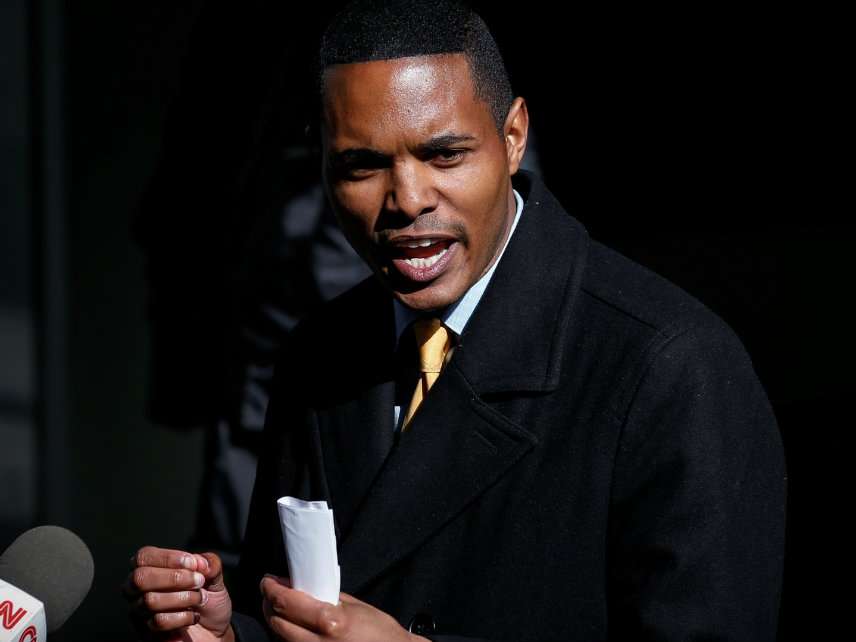

NYC Councilman Proposes Cash-Free Business Ban to Battle 'Insidious Racism'

Businesses owners, not politicians, should have the final say over how their customers pay.

With many establishments moving away from accepting physical currency, a New York City councilman has proposed legislation that would prohibit businesses from going cash-free.

New York City Councilman Ritchie Torres (D–15) introduced a bill Wednesday that would make it "unlawful" for restaurants and retailers "to refuse to accept payment in cash from consumers." Businesses found to be in violation would have to pay a $250 fine the first offense, and a $500 fine for each repeated offense.

Torres told Grub Street he sees cash-free policies as "racially exclusionary in practice." According to a 2015 study from the Urban Institute, 11.7 percent of New York households had no bank accounts. The survey did not break down its results by race, though a national survey released last month by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) did: Roughly 6.5 percent of American households were unbanked last year, the FDIC said, including 16.9 percent of black households and 14 percent of Hispanic households.

Cashless businesses "gentrify the marketplace," Torres told Grub Street. "On the surface, cashlessness seems benign, but when you reflect on it, the insidious racism that underlies a cashless business model becomes clear," he added.

Torres' legislation, cosponsored by six other councilmembers, is actually pretty mild, all things considered. A similar bill proposed in Washington, D.C., earlier this year would have made it illegal for companies to either refuse cash or offer discounts for paying in cash, with both violations punishable by fines ranging from $1,000 to $8,000. A cash-free business ban introduced in Chicago last October, meanwhile, threatened daily fines of $2,500, as well as the potential revocation of offending businesses' licenses.

Both bans have yet to be enacted. In fact, cash-free businesses are largely legal in 49 states. Only Massachusetts has a law on the books banning establishments from refusing cash.

Yet the rise of cash-free businesses can be explained without resorting to accusations of racism. For one thing, there's a lot of time, effort, and money that goes into accepting and processing cash. "Cash has to be handled. It has to be stored in a [point of sale] system. It has to be counted at least every shift. At the end of the day it has to counted and tallied into a sales report," John Gordon, founder of Pacific Management Consulting Group, a restaurant consulting firm, told Reason's Christian Britschgi in October 2017, around the time that Chicago's ban was proposed. Gordon also explained that cash can be miscounted or stolen, and that some businesses need to pay for armored trucks to take their cash to the bank.

Many companies launch with cash-free payment models to protect their employees; the absence of cash transactions has long been cited as a safeguard for Uber drivers, for instance.

Going cash-free is easier for many types of businesses, but it can also make things easier for consumers. Non-cash forms of payment are getting faster by the day, meaning cash-free establishments can offer faster service. Plus, consumers can more easily keep track of what they're spending.

But what about the alleged discrimination against poor people and minorities? Well, as Britschgi argued in July, it's not as if retail businesses want to turn away paying customers. It is conceivable, though, that the businesses going cash-free are the ones where people rarely pay in cash anyway. For those establishments, it just makes more sense to eliminate cash transactions altogether.

It's also worth noting that cash-free establishments tend to be on the pricier side. Is going cash-free, then, a form of price discrimination? Maybe, but I don't see very many politicians trying to regulate how much restaurants can charge for food.

Moreover, statistics suggest the number of people without bank accounts is steadily decreasing. The 6.5 percent of unbanked households in the country as of 2017 is down from 7 percent in 2015, 7.7 percent in 2013, and 8.2 percent in 2011. In New York, meanwhile, the unbanked rate dropped from 14.3 percent in 2011 to 11.7 percent in 2013.

Businesses owners, not politicians, should decide what forms of payment they'll accept, and consumers who prefer to pay in cash can take their business elsewhere. The market is pretty good at these kinds of transactions, especially since private establishments have to compete to stay in business.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

So large numbers of businesses not accepting cash is in no way racist because everyone has a bank account and a credit card but requiring an ID to vote is totally racist because minorities don't have ID.

Way to keep a consistent message reason.

I think this is a good idea. People should be able to use cash. Being able to use cash is essential to our privacy and freedom. The day cash goes away will be the day the government will assume total control and have total knowledge of our spending.

So large numbers of businesses not accepting cash is in no way racist because everyone has a bank account and a credit card but requiring an ID to vote is totally racist because minorities don't have ID.

Huh? John, the councilmen is saying that not accepting cash is racist because some black and Hispanic people don't have them and wants to force business to accept cash. Many businesses don't want to accept cash because of theft, cost of handling and that is what he thinks is the problem...

I am not saying the councilman is being in consistent. It is reason that is being so.

I don't recall any writers on Reason (there are multiple writers who work for Reason, who may hold different opinions) saying voter ID laws are racist, in fact there are a few articles I've seen stating it is not racist. Voter ID laws are bad because they are pointless, the voter fraud they are supposed to prevent doesn't exist in any appreciable amounts. They are just a solution in search of a problem.

This is a stupid law that is almost certainly fighting something that never will become particularly popular. But...

It is easy to see why a politician might be scared that this would become a way for establishments to not-so-subtly position themselves to exclude the check-cashing crowd from their clientele. (As is of course their right.)

And, I was just going to bring up what John, who is of course not as ideologically committed to strict libertarian principles as most here, said before I saw his comment. If there ever were a law to "meh," it would be this one. The overwhelming, enormous tide of future history is sweeping in exactly the opposite direction of this law--to banning cash. Alone among various intrusions on personal liberty, we have about the least to fear of this one--mandating cash--getting out of control. Banning cash is the very most fervent global "smart policy" vision of the "centrist technocrat" crowd I am always bitching about--the people who will actually rule the future, not the absurd Ocasio-Cortezes. If the hard-lefties want to throw their silly little monkey wrench into their masters' plans, then meh; I ain't gonna stress that hard on it.

Huh?

So, in the name of freedom, you support using coercion to force people to accept the government's fiat currency?

Way to keep a consistent message John;)

can i pay fine w/visa?

EBT?

EBT?

"Unbanked" is not the same as "cash only". As the Urban Institute study linked in the article points out, while 11.7% of New Yorkers were unbanked (defined in the study as not having a checking or savings account), many of those people use prepaid credit cards and other forms of electronic payment. (Page 15 of the report specifically notes that "some respondents reported preferring a prepaid card over a bank account because they were concerned about money being withdrawn from their bank account" without their consent.)

It is also worth noting that according to the same study, the percentage of the "unbanked" continues to fall steadily both nationally and in New York. So you've got to wonder why this is suddenly a problem for the young Councilman.

Also, I'm not sure having a bank is particularly good. It's not bad. It's neutral. If someone doesn't use a bank and is cash only I don't think they're somehow being deprived. They just made a choice.

Libertarian bigots are upset that a black man is finally protecting the rights of underprivileged communities of color. Refusing to accept cash is dog whistle politics of the worst sort imaginable. It dehumanizes black people by regarding their currency as inferior to that of the white man. Sick.

Ritchie Torres is doing the right thing, and history will look back on him with gratitude. The next logical step is to start erasing the taint of white supremacy that actually appears on our currency.

My suggestions:

1. George Washington --> Reverend Al Sharpton

2. Abraham Lincoln --> Kenan Thompson

3. Alexander Hamilton --> Maxine Waters

4. Andrew Jackson --> Kamala Harris (Harriet Tubman was a gun nut.)

5. Ulysses S. Grant --> Beto O'Rourke

6. Benjamin Franklin --> Barack Obama

Kenan Thompson might prove too controversial, but I still think his role as creator of Saturday Night Live is significant enough to merit such distinction. Nevertheless, I would also be fine with putting Jesse Jackson or Stacey Abrams on the five-dollar bill.

Why on Earth did you put Kenan on there in the first place? Is it in recognition of the excellent $5 menu at Good Burger?

Good Burger, with its class-conscious approach to comedy and emphasis on racial representation, was a trailblazing piece of African-American cinema. Sadly, the nation's predominantly white and male film critics panned it, because their privilege shielded them from its complex themes.

2 dollar bills are too obvious in their racist-ness and must be eliminated, I take it?

I'd be fine with Jackson being replaced by Frederick Douglass.

And put Thomas Sowell on the $100.

Thomas Sowell is a white conservative in blackface. So is Walter Williams.

You're right.

Both Sowell and Williams want blacks to get off Uncle Sam's plantation, think for themselves, get an education, obtain gainful employment, and be responsible.

How sick is that?

I know you're a parody, but damn that was racist as fuck.

I'd be fine with Jackson being replaced with just about anyone. I was totally fine with the movement to replace Jackson with a black person. Fuck that guy.

Whoa why all the Jackson hate? I mean there's the Indians but I think we're all pretty much bracketing nearly everything to do with race by common agreement when it comes to celebrating the early Republic, as a nation. It's like, everything these cats wanted for white people, that's our shared national vision of what all people deserve. And it's beautiful and sacred.

I say leave all the money exactly as is if we must still have Fed notes. But if we must change, axing Hamilton is the way to go. Swap him for Douglass or Tubman, would be a good idea. Douglass is way more photogenic; motherfucker looks like he was born to be on money. But some people will want a woman, which is probably understandable.

That, or we could go back to the ideological idea and consider being on a Fed note a dishonor. In that case, recent outrage was correct--Hamilton "deserves" more than anyone to be on a bill; whereas it would have horrified Jackson.

Why don't we move Madison from the $5000 note and put him on the $100, then move Franklin to the $20.

Not a bad idea. Though no one has printed anything above a $100 since 1946, and they haven't even been usable currency since the 1960s, so poor Madison is being rescued from an obscurity far greater than even you suggest! Also why the shifting; just put Madison on the $10 (or the $20 for you Jackson haters).

Jimi Hendrix!

What about Bill Hicks, 5 note?

6. Benjamin Franklin --> Barack Obama

If you can't see the systemic racism of people doing cocaine off of a black man's face, a community that has been ravaged by cocaine and crack, then there is no hope for you.

I deliberately avoided white people, prioritizing blacks and Hispanics (such as Beto) instead. Nevertheless, my straight white privilege precluded me from ensuring that women and members of the LGBTQIA community were represented.

I'd love to see Charlotte Clymer replace that racist bitch George Washington on the quarter.

One minor problem, they don't get much whiter than Beto. Did you get confused by the culturally appropriated nickname or were you unaware that he's as pasty white as his parents Pat Francis O'Rourke and Melissa Martha Williams.

And here I thought you groked the GOOG. Personally, I'm disappointed because it's like you didn't even try.

Beto? Why not Elizabeth Warren?

Personally, I'd vote for:

Clarabelle

Bozo

Ronald McDonald

Keystone Kops

Krusty the Clown

...

Excellent point, Kirkland, you bigot! Your list of six had only two women (need I even point out that it was entirely cis as well), and despite your pathetic gesture of removing Andrew Jackson did nothing to recognize the race that he slaughtered. Are they only the stuff of history books to you, rather than a proud and living people?

Andrew Jackson-->Elizabeth Warren

Fixed with Native American representation

Actually, make it:

Ulysses S. Grant -->Elizabeth Warren and you score a twofer by eliminating the vanilla white O'Rourke with someone who is much, much browner.

George Washington-->Barack Obama

Come on this one is obvious.

Why not just force retailers to accept SNAP benefits instead of cash?

Another excellent idea.

After the libertarian bigot Thomas Massie

My mistake. I accidentally submitted my last comment in anger when I heard another Starbucks patron mock Elizabeth Warren a few tables behind me. Anyway:

Another excellent idea!

After the libertarian bigot Thomas Massie mocked the wonderful notion that everyone is entitled to food stamps, it is imperative that food stamps also be available as a form of currency. In fact, food stamp recipients should get too sets of vouchers, one for food and one for currency!

Of course, the right-wing authoritarian class is too prejudiced to let that happen. Their white privilege and religious fundamentalism shields them from understanding human suffering.

Note: I boycotted Starbucks after their patrons refused service to those two black men a few months back. But the only other option in this town is the Chick-fil-A, and frankly, I have no interest in contributing to the pain felt by the LGBTQQIAA+ community by frequenting that bigoted mecca to Christian fundamentalism.

In fact, food stamp recipients should get two sets of vouchers, one for food and one for currency!

Is that so the government can treat currency stamps the way they do food stamps, limiting what can be purchased with them to what progressives think poor folks should have?

if so, I note there is a thriving black market in food stamps that sidesteps those restrictions.

Look, your white privilege is keeping you too steeped in the current power paradigm. Having a 'currency' and having 'food stamps' and the 'currency' being 'better' than 'food stamps' just ensures that the less fortunate are heaped with disdain for not having the 'better' item. We need to tear down class distinctions - all 'currency' should be 'food stamps and food stamps alone.

Well someone didn't get the progressive talking points on eliminating cash so they can track all transactions.

What about all the businesses that are Bitcoin free? That kinda leaves libertarians out in the cold, no?

Cash should be legal for all transactions. If it is legal tender in the US and the transaction occurs in the US, you should have to accept the legal tender. Sorry that is inconvenient.

Damn straight. Bitcoin and cryptocurrency should also be illegal.

I could care less about crypto-currency, or if 2 parties agree to settle debts with trade, naked selfies, boxes of Tide Detergent, or seashells.

But the US Gov't currency says right on it "Legal Tender for All Debts, Public and Private". Not "Legal Tender for All Debts, unless the Seller is inconvenienced by having to handle hard currency."

Isn't cash free already illegal? The Dollar is legal tender in the United States. I was under the impression that you were expressly forbidden from not accepting the US Dollar in payment for goods or services.

No. That is a common misperception. Your dollar bill says, "This note is legal tender for all debts public and private" (emphasis mine). You must incur a debt to a creditor for this provision to take effect. You are not, for instance, considered to have taken possession of a piece of gum simply by carrying it up to the bodega counter. If on the other hand the guy lets you walk out of there and pay him later, you will have incurred a debt to him.

I learned this as a little kid when I tried to pay at a bodega with one of the new yellow dollar coins when they first came out. The bodega owner refused to accept it because his customers did not want to get them back in change from him. I put up a stink but it turned out he was right.

You must incur a debt to a creditor for this provision to take effect.

Say, by bouncing a check or having a card refused?

No.

Even then, being 'legal tender' for that debt does not require someone to accept it in payment for that debt.

U.S. Department of the Treasury:

Q: I thought that United States currency was legal tender for all debts. Some businesses or governmental agencies say that they will only accept checks, money orders or credit cards as payment, and others will only accept currency notes in denominations of $20 or smaller. Isn't this illegal?

A: The pertinent portion of law that applies to your question is the Coinage Act of 1965, specifically Section 31 U.S.C. 5103, entitled "Legal tender," which states: "United States coins and currency (including Federal reserve notes and circulating notes of Federal reserve banks and national banks) are legal tender for all debts, public charges, taxes, and dues."

This statute means that all United States money as identified above are a valid and legal offer of payment for debts when tendered to a creditor. There is, however, no Federal statute mandating that a private business, a person or an organization must accept currency or coins as for payment for goods and/or services. Private businesses are free to develop their own policies on whether or not to accept cash unless there is a State law which says otherwise. For example, a bus line may prohibit payment of fares in pennies or dollar bills. In addition, movie theaters, convenience stores and gas stations may refuse to accept large denomination currency (usually notes above $20) as a matter of policy.

That's never been the case. Hell, even the government doesn't have to accept specific denominations if it chooses not to.

The only thing that *has* to be accepted in Dollars is your tax payment.

It's legal tender for all debts public and private. ALLL DEBTS!!!! God fuckingcdammn u can't reSd the fucking currency.

Username checks out.

...just when you thought the stupid gene in Mr. Torres was in control...

He shouldn't be so narrow-minded. People who like cash will practice their own selectivism, and people who like cashless won't be able to patronize cash-only shops.

"Yet the rise of cash-free businesses can be explained without resorting to accusations of racism."

You seem to lack imagination.

Remember how Tom Lehrer, in his song about Smut, said "When correctly viewed/everything is lewd"?

Well,

If you'd only face it

Everything is racist

"Yet the rise of cash-free businesses can be explained without resorting to accusations of racism."

You seem to lack imagination.

Remember how Tom Lehrer, in his song about Smut, said "When correctly viewed/everything is lewd"?

Well,

If you'd only face it

Everything is racist

One thing that never seems to be mentioned is that these poor people and minorities *are choosing* to forgo banking and electronic payment services. Its a lifestyle choice.

Now, there are some good reasons to not have bothered to have gotten a bank account if you're being paid in cash and don't have private transportation - but not good enough for it to rise to 'discrimination' if someone doesn't want to take your cash. Still, there are alternatives - prepaid debit cards, for example.

Nice Post!Keep Posting

Strategic Management Assignment Help

I am split on this. A low cost restaurant in my area, Amsterdam Falafel, attempted to go cash free and there was a large backlash. So the restaurant continues to use cash. The restaurant only sells falafel, fries and sodas, waters and I think you can buy brownies. You can probably get something to eat there for as little as $4, but a typical meal is $6. For the city that is cheap and for the unbanked that would take a low cost restaurant option away.

However, most businesses that want to go cash free, probably have few customers that pay cash in the first place, so it seems like it would make things easier for them.

T-Mobile is offering a mobile checking account service. There are visa gift cards you can buy and put cash on and use them like a credit card. So there are options for the poor to get around being unbanked and still access these services.

Of course, cash-free would mean that every financial transaction you make leaves a paper trail, but no one need worry about that, right?

I would like to thank you for the efforts you have made in writing this article. I am hoping the same best work from you in the future as well.

Marketing Assignment Help

Nursing Assignment Help

Management Assignment Help

Accounting Assignment Help