Mad Genius

The Reason founding story

The New Republic was launched in 1914 by three of the most famous intellectuals of the Progressive era: Walter Lippmann, Herbert Croly, and Walter Weyl. National Review was introduced in 1955 by an oil tycoon's son named William F. Buckley, already notorious for provocative books criticizing Yale and defending Joseph McCarthy. The Weekly Standard was founded with Rupert Murdoch's money 40 years later by former Dan Quayle speechwriter William Kristol, whose legendary magazine-editor father Irving was considered the godfather of neoconservatism. Prestigious journals of opinion often emanate from prestige.

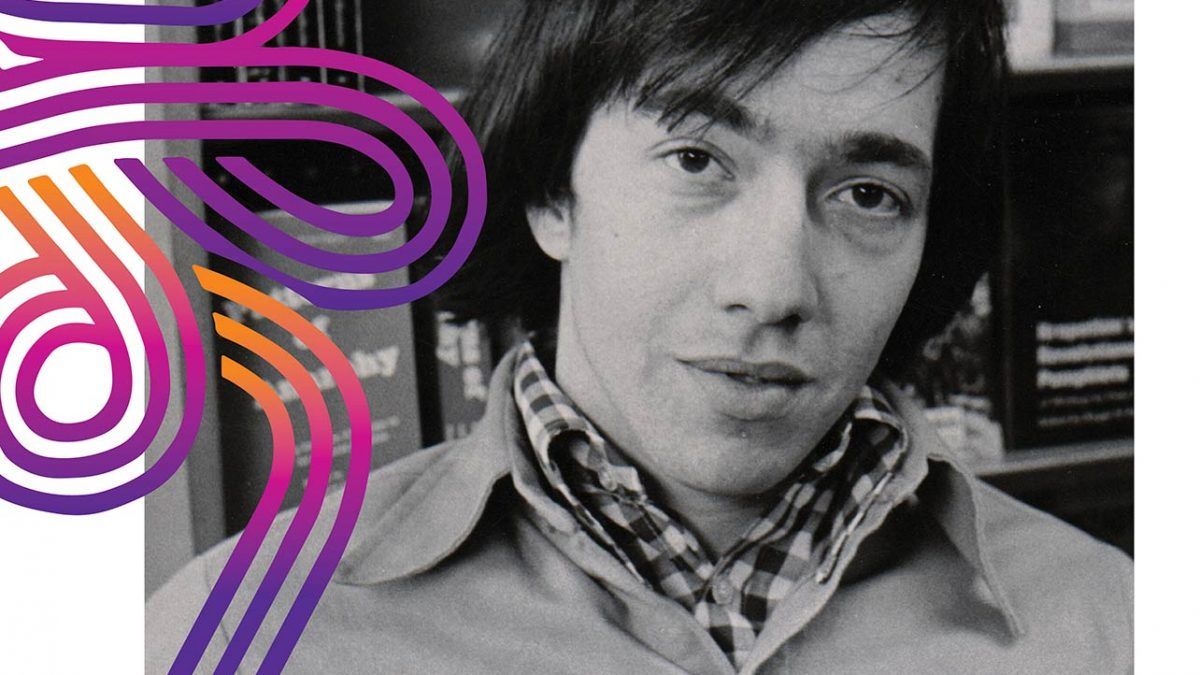

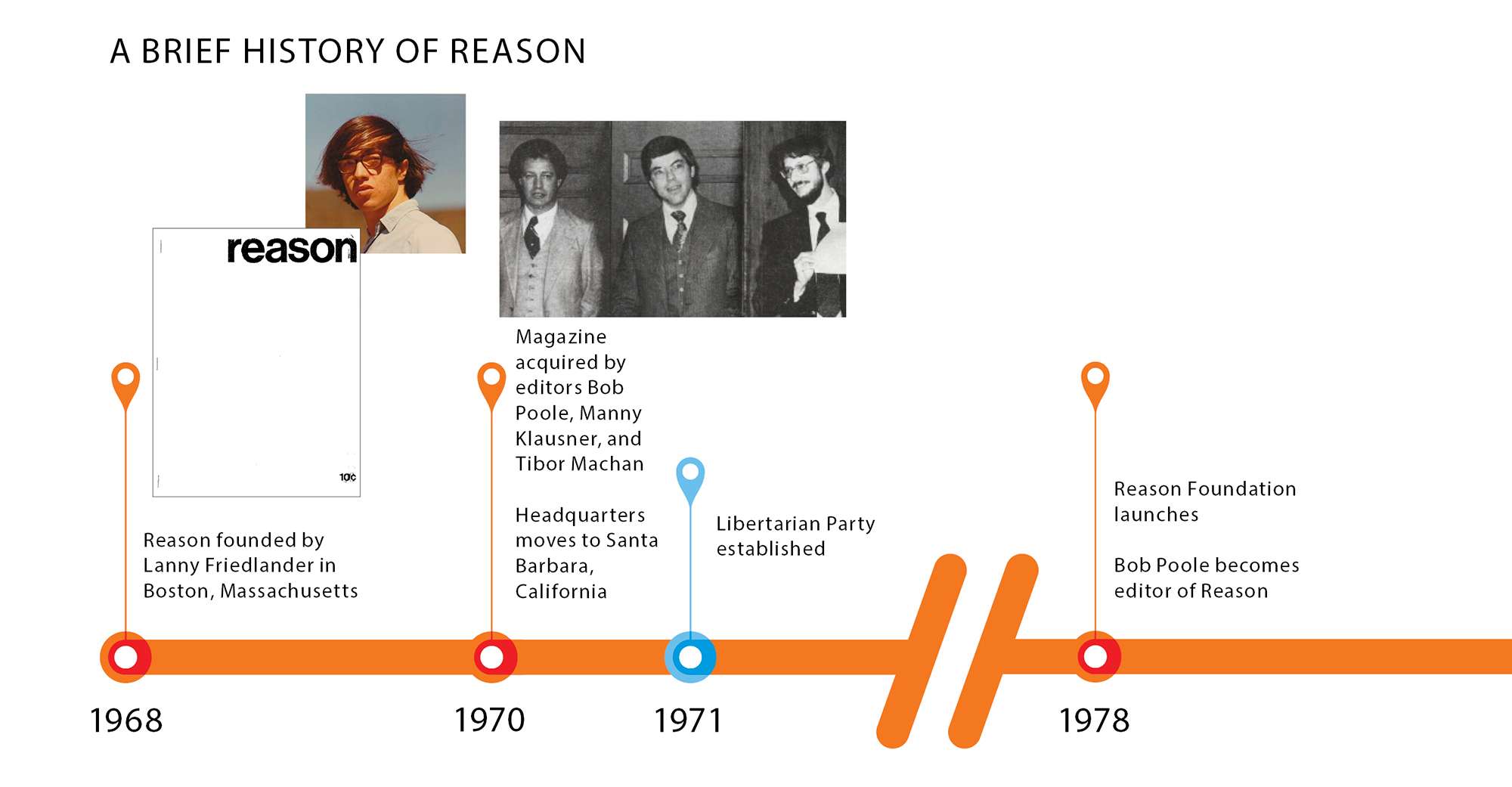

Not so Reason. The magazine you are reading was the brainchild of a 20-year-old Boston University student nobody had ever heard of named Lanny Friedlander, who stapled together and mailed out the first mimeographed issues from a hopelessly disorganized room at his mother's brick house in Brighton, Massachusetts. You will search in vain for any editor's note in the history of The Nation or Mother Jones with a lead like this opening line from Friedlander in January 1970: "I drive a delivery van for a living."

From these inauspicious beginnings, Reason has grown to a magazine with a circulation of over 40,000, averaging more than 4 million visits online per month and producing videos that were watched 48 million times on YouTube and Facebook in the last year—in addition to a practical-minded public policy shop that helps reform public pensions, privatize government services, and build better highways. Almost all of that achievement took place after Friedlander exited the scene. In 1970, after two thrilling but erratic years, Reason's founder sold the publication's thin assets and thicker liabilities for less than $3,500 to the industrious California-based trio of systems engineer Robert W. Poole Jr., libertarian lawyer Manuel S. Klausner, and neo-Objectivist philosopher Tibor Machan. (Their significant others, who also joined the partnership at the time, were eventually bought out.) In 1978, they launched the foundation that publishes the magazine to this day.

By the time both Reason and the modern libertarian movement began to flourish, one of the key architects of both had fallen off the grid, never to return. Yet Friedlander's distinct vision is still visible, in the form of the magazine's lowercase, sans-serif logo, its willingness to gather in various strains of libertarianism for examination and debate, and a certain natural sympathy for outsiders, eccentrics, dreamers. "He was bold, amazingly gifted, socially uncertain," recalls Mark Frazier, then a high school student who helped with paste-up and other tasks on some of those early editions before moving on to a long career in the free cities movement. "He followed a compass that set many different things in motion."

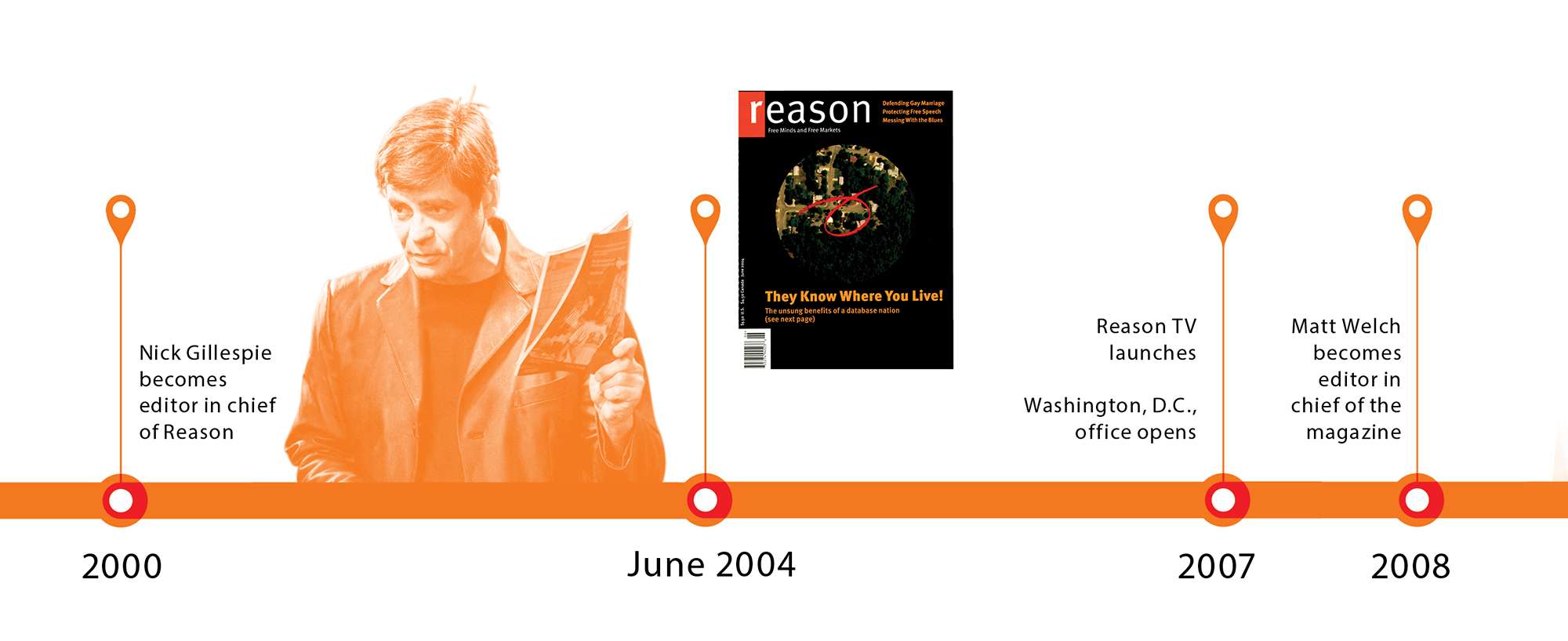

Who exactly was this sui generis spark, how was he able to rise above the 1960s and '70s din of short-lived libertarian-world newsletters, and why did he flame out so fast? These elusive questions have haunted a succession of Reason captains. Upon Friedlander's death in 2011, Nick Gillespie, editor in chief of the magazine from 2000 through 2007, wrote that in the absence of any information, he had "started thinking of Lanny as libertarianism's answer to Syd Barrett, the mad genius founder of Pink Floyd who got something great started and then couldn't or wouldn't live in the world he did so much to create." Even people who knew Friedlander in the flesh are hazy on details, tending to project onto his sparse canvas the arc of their own life journeys.

A closer examination on the occasion of this 50th anniversary begins to fill out the picture of Reason's starkly minimalist origin story. Lanny Friedlander was an Objectivist who believed in big-tent libertarianism, a student protester who reviled other student protesters, and an anti-war/anti-draft activist who volunteered for the Navy. He was professionally charismatic and personally introverted, an exacting truth seeker and unreliable narrator, a systemic thinker and disheveled coordinator. ("The printed format of this issue," he wrote when announcing the magazine's first offset-press edition in September 1969, "does not represent a guarantee that the next issue will also be printed.") He will likely be remembered most for his striking sense of art direction—Wired co-creator Louis Rossetto, who first encountered Reason as an undergrad at Columbia University, said in 2011 that the publication "was my gateway to good design"—yet when describing himself, Friedlander preferred the term "writer/intellectual."

That writing contained a breadth rarely seen among young adults of any era. Friedlander made prescient and detailed predictions about the future of personalized telecommunications, argued persuasively that "pollution is theft," and applied Austrian-economics analyses to the question of "how the police would operate in a free society." At turns theoretical and practical, pedantic and poetic, his voice vibrated with a visceral rage when touching on the dehumanization of modern institutions. "Whatever reason a parent might have for leaving his children in the care of the state," he snarled in January 1970, talking about not orphanages but public schools, "it will not diminish their intellectual death, nor mitigate their emotional torture."

Friedlander was an Objectivist who believed in big-tent libertarianism, a student protestor who reviled other student protestors, and an anti-war activist who volunteered for the Navy.

As fate would cruelly have it, Friedlander spent much of the rest of his life institutionalized in Veterans Administration facilities and halfway homes, chained to the dulling anchor of antipsychotic drugs—a diagnosed schizophrenic under the wary eye of the paternalistic state.

But before that sad, smothered slide, there was a bracing boldness to go somewhere truly new. "When Reason speaks of poverty, racism, the draft, the war, student power, politics, and other vital issues," Friedlander promised in his opening-issue manifesto, "it shall be reasons, not slogans, it gives for conclusions. Proof, not belligerent assertion. Logic, not legends. Coherance [sic], not contradictions. This is our promise; this is the reason for Reason."

Boston Uncommon

Back in the late 1960s, as the old saw goes, you could fit the entire libertarian movement into Murray Rothbard's New York apartment. So where did that leave Boston?

There was David Nolan—co-founder of the Libertarian Party and inventor of the Nolan Chart political quiz—and his first wife Susan Nolan (a key early figure in the L.P. as well), but beyond that not really much in the way of libertarian circles to hang out with. "No circles, no circles," laughs Doug Messenger, then a young guitarist at the Berklee School of Music and a budding Objectivist. "But there were people you'd see."

Chief among those visiting attractions was Ayn Rand, whose ideas about the primacy of reason and the virtue of selfishness were just gaining ground. As Jerome Tuccille put it in the title of his hilarious 1971 semi-fictionalized snapshot of libertarianism, "it usually begins with Ayn Rand," and that's indeed how things started for Friedlander, Messenger, Frazier, and other scattered seekers around the greater Boston area.

The closed philosophical system created by Rand and then squabbled over by her interpreters, Objectivism, was the rallying point for libertarianism circa 1968, and the starting point for its soon-to-be-flagship journal. "Reason is editorially in agreement with the philosophy of Objectivism," Friedlander announced in his inaugural issue, though "the responsibility for the contents belongs to the editors." The philosophy's preoccupations and jargon didn't necessarily play a lead role on the page, but there were still headlines like "Welfare: An Altruist's Nightmare." Editors' notes from the first two years included dozens of names and addresses of "on and off campus pro-Objectivist groups" so as to "encourage correspondence and inter-organizational work where such would improve the quality of the groups involved."

Messenger and his wife attended a speech Rand gave about the pope and birth control at Boston's Ford Hall Forum in December 1968. "Very cold out there, below 32," he recalls. "After the lecture, we waited outside. 'Let's see if we can meet Ayn Rand. Let's see.' Sure enough, she came out, and I got to talk to her. I asked a question, and the people with her wanted her to leave, and she said, 'I like his question. You go ahead.' She gave me a little five-minute speech…and she said, 'I've never thought of that, but it's a serious subject, and it's worth looking into.' It was this weird little lady! She looks like a little Russian peasant, right? These huge eyes that were ridiculously big and looking up at me."

By 1970, Messenger was out in California, playing guitar in Van Morrison's touring band and contributing to such classic albums as Saint Dominic's Preview. But between Rand and Van, there was Lanny.

"He was very young. Dark hair, nice tie, really cool guy to be around," Messenger says. "He'd come by my apartment, he'd show us his latest rag, and we'd talk about it. We'd say, 'Man, that's a good effort.' We liked his enthusiasm."

"It was a little rag on mimeograph, sometimes just one little sheet. It was more blurbs than real articles," he continues. "He wasn't that intellectual, but he was ambitious, all jazzed about Objectivism and so forth.…Strange kid."

Friedlander shared Messenger's enthusiasm for music—one of the young editor's most effusive bits of early writing was a 725-word blast in the December 1969 issue about how, "while we weren't watching, nor perhaps caring, rock music has begun to grow up," as evidenced by the latest orchestral releases from Deep Purple, the Moody Blues, and Chicago. "He was really into music. He was a child of the '60s," his late-in-life attorney and fiduciary George Murphy says, recalling a visit the two made to one of the last Strawberries CD stores near Lowell, Massachusetts, not long before Friedlander died. "He asked the clerk, probably like a young punk rocker, if they had any Procol Harum.…He was stuck in that time period, you know? That was the time of his youth. That's when he was the most productive."

Friedlander's consumption of all forms of media was voracious, Frazier recalls. There were comic books (Reason published some panels by legendary Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko in 1969), the latest cutting-edge book and periodical graphic design from nearby MIT Press, mail-order newsletters and 'zines. "He had an encyclopedic knowledge of the Objectivist and libertarian movement," Frazier says, teenage hero worship still evident in his voice nearly a half-century later. "Lanny had a personal way which was essentially tuned into the deep context in terms of philosophy and politics, and an ability to put in graphic form, and in his writing, very acute, incisive, intelligent kinds of expression. And he did it with a sense of humor."

Some of that wry wit made its way onto the page. "Out of kindness to the English language," Friedlander wrote in a November 1969 introduction to a reprinted essay by Jarret Wollstein, "certain sentences in Mr. Wollstein's letter have been modified." Friedlander's promotion on the masthead of a 19-year-old Frazier to publisher ("quite an elevated position for somebody who was an intern," Frazier says) could be seen as humor, gratitude, or both. After all, it took dogged efforts by Frazier to get involved with the magazine at all. "I [had] called Lanny and said, 'I'd love to help.' My impression of him just over phone was someone who was very introspective and someone who sounded like they'd appreciate the help, but he didn't do much in the way of trying to pull me in. But I persisted."

Friedlander's writing in the face of America's annus horribilis of 1968 was bracingly direct, provocative, and original. He confronted the burning issues of the moment—violence, war, race relations, campus upheaval—with boldly counterintuitive takes. "It is the initiation or threat of initiation of physical force by the government that is the major cause of violence in America (or any nation)," he wrote in response to the year's political assassinations and race riots. "Treat a man like an animal and he will act like one." Both Jim Crow and minimum wage laws were unambiguous examples of racism, he argued. The New Left and George Wallace had more in common than either would ever admit.

"Either a man has a right to use his body however he pleases (as long as he doesn't violate the same right of others) or he does not," he proclaimed in the May 1970 issue, after National Guardsmen shot and killed four students at Kent State University. "Those liberals who denounce the soldiers at Kent, who yet applaud [Attorney General John] Mitchell's valiant attempts to save the children of America from themselves, are trying to straddle a barbed wire fence."

Bob Poole saw a small classified ad for Reason when reading another libertarian newsletter, Innovator. "The content was surprisingly good, written almost entirely by Friedlander himself," Poole recounts in his new memoir, A Think Tank for Liberty (Jameson Books). He was "a good writer and editor," Poole adds, "with an excellent design sense." Ah, that design.

Even today, your mailbox probably still fills up with tacky political fliers of grinning politicians, unwanted laser-printed four-pagers, cluttered store catalogues. Now imagine in the less colorful mix of a half-century ago a nearly blank page, with a magazine logo on the top right, and then halfway down the page, in lowercase text on two unevenly matched lines, the cover line "black capitalism." The Freeman, published back then by the Foundation for Economic Education, may have had 100 times the circulation of early Reason, but Friedlander's creation leaped out of the crowd.

"It looked like nothing else out there," Rossetto told The Village Voice in 2001, upon the occasion of a Reason redesign that Rossetto had consulted on. "There's almost a timeless elegance in his design," Frazier says. Recalled early contributor Tibor Machan in his 2004 memoir The Man Without a Hobby, "Among other virtues, Reason boasted a striking graphic design."

Visual elements that decades later would become faddish in art schools were there from the beginning. "Lanny was a fan of Massimo Vignelli, so Reason had a perfect Swiss grid, very clean and pure, lots of white space, ragged right, Helvetica type, conceptual illustrations," Rossetto told the Voice. "I liked that, and the fact that it was anti-establishment without being part of the new establishment—the New Left—and without being either crank left or kook right. And it had this bright, shiny optimism and unshakable faith in the triumph of good ideas. Now that I look back, in many ways it inspired me to get involved in making magazines."

Even with a small print run and spotty publication schedule, Friedlander's mix of startling visual presentation and contrarian writing created an almost instant momentum, tantalizing early readers and contributors alike with an infectious sense of as yet unimagined possibilities.

"What was striking, and it comes through on some of the back pages of the issues, is the sense of discovery, an electric kind of feeling," Frazier says. "At a time when there were many bleak currents, you can see in the letters and the classified ads that came in, people in a sense recognized there was something there. There's a current that people were awakening to and beginning to cherish. And the early articles that people were sending in, essentially out of the blue, were of exceptional quality.…It was an example, I think, of spontaneous order stepping up. It was energizing."

The editor's note in the December 1969 issue (which contains pieces by Poole and Machan) is a happily meandering snapshot of a movement on the grow. Friedlander talks about a new "laissez-faire" button he designed for sale, complete with a simple and elegant image of a chain broken in the middle; gives his advice (probably "much too late…to be helpful") on resisting the U.S. Census; and enthuses about his discovery of jury nullification: "I recently came across what must be one of the most effective devices yet for libertarians to cheaply and quickly exert ideological pressure on the political structure." Look out world, the libertarians are coming!

New York Stories

Potential can be easier to see when it is in the process of being wasted. Poole, a Sikorsky Aircraft engineer who had written a serious piece about airline deregulation for Reason's first professionally printed issue, went to pay Friedlander a visit at his mom's house in Brighton shortly thereafter. "What a character," he wrote in notes after the trip. "Not the stereotyped Objectivist but certainly an individual—longish unruly hair, sloppy old clothes, sloppy room, rambling mind—but very intelligent."

There was at least some order beneath the chaos. "I had some experience doing paste-up on prior publications," Frazier remembers, "but he was a league ahead of me in virtually every way in terms of the knowledge of graphic design, of publishing. He had his own system of hand-applying a headline onto the paste-ups for the offset printer."

Still, the disorganization was such that Friedlander had to hit up his own contributors for money to keep the venture afloat. As Poole recounts in his memoir, "It became clear then that Lanny had no head for business."

The Poole/Klausner/Machan troika cooked up a rescue-and-expansion plan, flew Friedlander out to the West Coast on an unrelated grant, and got the deal done. "Lanny was a difficult house guest, and the negotiations were somewhat trying, but in the end we reached agreement," Poole writes in his understated style. Although the founder was kept on as a contract editor for six months, Poole recalls that the working relationship was not easy and did not last.

Yet Friedlander was still a force. In March 1971, after having sold Reason and moved to New York City, he was one of several libertarian luminaries (including Tuccille, Rothbard, and Walter Block) to give remarks at a Columbia University conference called "Shaping the Future"—a seminal moment for a generation of young libertarians. The L.P. Historical Preservation Committee placed many of the speeches from that event online in 2017, and the Friedlander you hear there is eloquent, deep-voiced, unhurried, and eager "to change the emphasis of the libertarian movement from an armchair kind of movement to one where [our actual] ideas are effectuated, brought into existence." The only glitches in his presentations come when he interacts with the audience and becomes suddenly self-conscious, not sure how to read the room.

"He was a person of few words in conversation, and always seemed to be somewhat detached or inward in his way," Frazier explains. But "when he was in a meeting with someone, or giving a talk, he could go on and on and on a given point, and there was always a sense of elegance or beauty in his way of presenting things."

Friedlander's performance at Shaping the Future contributed to him landing a girlfriend, who stuck around for most of 1971. "I thought he was very smart from the conference, and having started the magazine," recalls the woman, who asked not to be named.

Early '70s New York City saw an explosion of libertarian activity—the 1970 creation of a state-level Libertarian Party (predating the national party by one year), noisy conferences and debates heralding new organizations and challenging old ones, and the 1972 opening of Laissez-Faire Books in Greenwich Village. "I got chummy with Lanny Friedlander, that broken genius who started Reason and challenged many of my conventional ideas," the late Andrea Rich, longtime impresario of the free market book publishing outfit, recalled in a Voluntaryist essay several years ago. There was "a lot of ferment, arguing, debate, and a lot of fun," says Gary Greenberg, who chaired the New York L.P. for much of the '70s and '80s and ran for Congress, governor, and Manhattan district attorney. "I thought it was the best time of the libertarian movement."

One of that era's biggest moments was the publication in January 1971 of a long New York Times Magazine essay by Columbia rabble-rousers Stan Lehr and Louis Rossetto titled "The New Right Credo—Libertarianism." Rossetto, who got his start in journalism at the Radical Libertarian Alliance newsletter The Abolitionist and then became president of that publication's short-lived but influential successor Outlook, credits Friedlander for helping inspire his career. "Weird to say, but for a while when I was a college sophomore, I just wanted to be Lanny," Rossetto recounted after Friedlander died. "In some ways, he sent me on one of the grand adventures in my life."

Despite being near the center of the libertarian universe, though, Friedlander was already withdrawing from it. "It's not like Lanny and I then hung out with those people. We did not. He was removed from that by then," his ex-girlfriend recalls. "He did not have a job in that time.…He would claim he was going on a job interview or going to see somebody about some [graphic] design thing, but nothing really came of it."

Friends say Friedlander had trouble navigating social engagements, opting to either medicate himself with marijuana or avoid such intercourse altogether. He never went to Libertarian Party organizing events and didn't even participate much when Rossetto invited him to come around the Outlook offices. "I think he was just there for self-stimulation," says Greenberg, a contributing editor there. "After that, there's a period where he just disappeared."

The wheels started coming off more often, and the evidence that he was suffering from schizophrenia began to mount. The mental illness that had plagued his mother and contributed to the dissolution of his parents' marriage appeared to be derailing a promising young career. "I ran into Lanny and he told me he had taken a bunch of LSD and ended up in the hospital," the ex-girlfriend says. "That was the last time I ever saw him." Friedlander's final byline in the magazine he created came in October '72, just shy of his 25th birthday.

After that, there were vague tales of troubled travels in the South, frantic calls for money, and a drunk and disorderly misdemeanor conviction in Miami in 1975. Somewhere within that flailing period—everyone's story is different, and official records are difficult to come by—Friedlander enlisted in the Navy, only to be discharged shortly thereafter on psychiatric grounds.

On the seeming riddle of an anti-war writer volunteering for the military during the tail end of a Vietnam War he despised, Murphy points out: "Military age is when the disease manifests itself, so they may go in as a normal 18-year-old, but by the time they're 20 or 21.…"

By the late 1970s, the people who started the decade so influenced by Friedlander were lucky to hear from him even once a year, and it wasn't always pleasant. "After he left New York," Rossetto told Reason after Friedlander died, "periodically I would get these psychotic phone calls from him that made me want to kill him, they were so upsetting." Soon, even those infrequent interruptions fizzled into silence.

'The Prospects for Immortality'

Friedlander, like so many patients on antipsychotic drugs, did not like them. "He'd basically say that when he's on the medication, it's like playing a record at a low speed," Murphy says. "But when he's off, it was like him doing acid."

At the V.A. facilities and group homes where he lived, Murphy says, Friedlander could come off like Randle Patrick McMurphy, the lead character in Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. "He'd be annoying to a lot of people, you know? He liked to tease. And if the person wasn't receptive to teasing, it would come to yelling and so forth, especially if there's other people in the group home there that have a similar illness or mental health issues." But as with McMurphy, there was some brainpower evident behind the razzing. "I could definitely tell that this is a guy who was exceptionally intelligent."

Yet so complete was Friedlander's break from his Reason-founding past that even Murphy did not believe his friend's account of his own biography. "Lanny was telling me that he was this great graphic artist and he started a magazine and everything, and of course I'm thinking this was the psychosis, you know? I was all incredulous."

Reinforcing that skepticism was the time Friedlander got anxious about losing his art portfolio. After a search, the missing satchel was discovered, "and just like in A Beautiful Mind, the art was like third-grade," Murphy says. "It was basically gibberish."

Ten years ago, when I was editing this magazine, I asked my wife, Emmanuelle Welch, a private investigator, to track down Friedlander for our 40th anniversary issue. After so many years of whispers and rumors and uncertainty, it didn't take long at all—he was in a veterans' home in Lowell, Massachusetts. In fact, while trying to verify his presence at the home, Emmanuelle suddenly and inadvertently got Friedlander on the phone.

"I said I was looking for the Lanny Friedlander who had founded Reason 40 years ago. Dead silence," she told me that day. "So I asked nicely, 'Is that you?' And he said yes. Then I explained that I was [looking for] him because Reason wanted to reconnect with him. Dead silence."

"I kept trying to ask: Would you like to be connected to them? Should I give them your number? He said no. I said I'm sorry if I upset you, and he said that's fine. I offered to give him my number so that he could contact me whenever he felt like it, and he said no. It wasn't a super firm or angry no, more like a 'ghost from the past' no.…He sounded more shell-shocked and wounded, and not at all angry at me, just very sad."

Through the help of longtime Reason reader and supporter Robert Smiley, we sent to Friedlander not long thereafter a care package of swag and a subscription to the magazine he had founded so long ago. Smiley even kicked in for a computer. "He was really thrilled that you guys took interest in him," Murphy says, though he had a "hard time" navigating the computer. (In August 2009, Friedlander did start a Twitter account, but he never managed to post.)

Reason breaking silence with its creator was reciprocated in December 2010, when the magazine's first editor sent a letter to Science Correspondent Ronald Bailey. "I think," Friedlander wrote by hand in response to a Bailey piece about developments in genomics, "you should take your thinking one step further and write about the prospects for immortality in the foreseeable future. Recently the Boston Herald printed an article about rejuvenating mice; about work going on at [the] Dana Farber Institute. I also wonder if magicians can reverse the effects of old age. Thanks for an interesting article about genomes."

As if his optimism about the future and the phrase prospects for immortality weren't poignant enough coming from a man who would die four months later, he finished with this killer kicker: "P.S. I started Reason magazine in 1968."

But Lanny Friedlander did more than just start Reason. He willed into being a demonstration project that you don't need money and other built-in advantages to launch a worthwhile journal of opinion. He showed people who didn't even know it that they were entrepreneurs, journalists, futurists, and even libertarians, that there was a different way of thinking and being in the world, that one could be revolutionary even while advocating the most modest of policy gains. Before his productive brain betrayed him, he was consumed with the question that challenges us all to this day: How do you make social change? In a world where there is no single right answer, how do we explore, maximize, and expand all the avenues for making the world a better place? "Not that the theory isn't important," he said at the 1971 Columbia conference, "but this seems to be a movement primarily of philosopher kings. And there's a need for all these things to happen. The left has been at least moderately successful at changing America, and we should be, too. We have better ideas, and they do work in the world, whereas the liberal programs are falling apart."

We don't know where Friedlander's interests would have taken him after the early 1970s—it could have been anything from advertising to econometrics to designing prog-rock album covers. Mental illness prevented us from finding out, and that misfortune haunts not just the people who loved him but all of us who inherited the world he helped create.

At Reason there is some slim consolation that, in the autumn of his life and as his magazine hit middle age, Friedlander himself belatedly began to hear the validation he had so long deserved. After we reached out to him, Murphy says, "that's when I knew that, 'Hey, he actually did found this magazine!'"

"Let's put it this way: When he passed away, he got his obituary in The New York Times, The Globe, and the Los Angeles Times. And I'll never get that. I'm going to be lucky if I get a little write-up in the local paper."

As Ayn Rand wrote in Atlas Shrugged—a line Oliver Stone paraphrased in his 2016 movie Snowden—one man "can stop the motor of the world." More heroically, perhaps, is the opposite: One man can start the motor, not just of one world but of several. That, in the end, is the legacy of Lanny Friedlander.

"The sense of quest, and stepping up personally when the odds are just overwhelming…is the best sense of what Lanny stood for," Frazier concludes. "Lanny put everything into making his values flourish and the ideas that we cherish in common to prosper. And so it's that quality, of someone who spent his days driving a delivery truck, learning how better to communicate in writing and visually. It was to invest in himself, but I think in a way that transcends any kind of narrow ego. He was doing this to make the world safer and freer for people. And that is heroism. This is a guy who will not be forgotten."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Mad Genius."

Show Comments (47)