Tom Wolfe Is Dead but the 'Me Decade' Lives On (and That's a Good Thing)

The world didn't just lose a transformative prose stylist. We lost our guide who still explains the contemporary world.

Tom Wolfe, the celebrated reporter, ethnographer, and novelist, is dead at the age of 88.

With his passing, we've lost the individual who more than any other writer transformed the practice of journalism since he first started writing for the late, lamented New York Herald Tribune in 1962. I'll leave it to others to assess Wolfe's contributions to literary style; the validity of his popular polemics on art, architecture, race relations, sexuality, and neuroscience; and the relevance of his caustic but illuminating feuds with such other major writers as Norman Mailer, John Updike, and John Irving. These are all fun to talk about, but they are ultimately ephemeral.

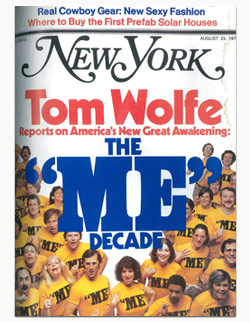

Wolfe's enduring—and fundamentally libertarian—contribution to contemporary discourse is the insight at the heart of his 1976 New York essay that christened the 1970s as the "Me Decade." Writing during a time when most wise men (and they were mostly men back then) were obsessed with inflation, unemployment, and other measures of macroeconomic malaise, Wolfe was nearly alone in underscoring that consumer goods and lifestyle options had been radically democratized in postwar America. Forget the soul-killing depredations of the Cold War, giant corporations, cheap money, rising taxes, and government's expansion into every nook and cranny of life, he counseled. Wolfe focused on the pent-up psychic demand for freedom, individualism, and meaning in a country that had recently withstood a decade-plus of Great Depression and World War. The only thing worse than the impending apocalypse due to nuclear war, environmental catastrophe, overpopulation, or the Second Coming was that the world wouldn't end and we'd have spent our time on Earth punching the clock for a soul-killing job with great dental benefits. In the goddamn Bicentennial Year, Wolfe argued, Americans were done with building Maslow's pyramid of needs for other people, especially their social betters. Who among us was going to follow slow-witted concussion-cases like Jerry Ford or lusting-only-in-his-heart Jimmy Carter into the twilight's last gleaming? It was our time to shine, baby!

The postwar economy had

pumped money into every class level of the population on a scale without parallel in any country in history. True, nothing has solved the plight of those at the very bottom, the chronically unemployed of the slums. Nevertheless, in Compton, California, today it is possible for a family at the very lowest class level, which is known in America today as "on welfare," to draw an income of $8,000 a year entirely from public sources. This is more than most British newspaper columnists and Italian factory foremen make, even allowing for differences in living costs. In America truck drivers, mechanics, factory workers, policemen, firemen, and garbagemen make so much money—$15,000 to $20,000 (or more) per year is not uncommon—that the word proletarian can no longer be used in this country with a straight face. So one now says lower middle class. One can't even call workingmen blue collar any longer. They all have on collars like Joe Namath's or Johnny Bench's or Walt Frazier's. They all have on $35 Superstar Qiana sport shirts with elephant collars and 1940s Airbrush Wallpaper Flowers Buncha Grapes and Seashell designs all over them.

As he did later in his most (and perhaps only) successful novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, Wolfe rooted his observations in detailed reporting on the reality of money and the trappings of class in everyday life. The passage above could never be written by other "New Journalists" such as Hunter Thompson and Norman Mailer because they were fundamentally obsessed only with themselves. Wolfe, like Joan Didion at her best, wanted first and foremost to understand and grasp social reality that transcended the self.

The turn to self-actualization deeply upset and offended both old-school, puritanical commies and starched-shirt Protestants who deeply believed in Max Weber even if they had never read him. Wolfe understood that the United States was shifting radically from a stratified, button-down society to one where everybody—rich and poor, black and white, male and female—not only had the means to live however the fuck they felt but had the moxie to do so. One of his early pieces for the Herald Tribune covered the introduction of macrobiotic dieting to the U.S.; it exemplifies his interest in how everyday people, long thought by eggheads and scolds not to have any autonomous interest in aspirational living, were starting to explore all sorts of freaky-deaky subcultures. His major works of the '60s, including The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, explored how people create meaning in a mass-cult world, sometimes by drug-fueled ecstasy and dropping out, more commonly by modifying production-line cars, clothes, and suburban activities such as grilling to their own individual desires.

My God, the old utopian socialists of the nineteenth century—such as Saint-Simon, Owen, Fourier, and Marx—lived for the day of the liberated workingman….He didn't look right, and he wouldn't…do right! I can remember what brave plans visionary architects at Yale and Harvard still had for the common man in the early 1950s. (They actually used the term "common man.")…By the 1960s the common man was also getting quite interested in this business of "realizing his potential as a human being." But once again he crossed everybody up! Once more he took his money and ran—determined to do-it-himself!…

Once the dreary little bastards started getting money…they did an astonishing thing—they took their money and ran. They did something only aristocrats (and intellectuals and artists) were supposed to do—they discovered and started doting on Me! They've created the greatest age of individualism in American history! All rules are broken! The prophets are out of business! Where the Third Great Awakening will lead—who can presume to say? One only knows that the great religious waves have a momentum all their own. Neither arguments nor policies nor acts of the legislature have been any match for them in the past. And this one has the mightiest, holiest roll of all, the beat that goes…Me…Me…Me…Me….

Wolfe was not uncritical of the turn to "Me…Me…Me…Me…" but unlike such scolds as Christopher Lasch, David Frum, and Robert Putnam, who saw only narcissism and social pathology in the democratization of liberation, the rise to ubiquity of aristocratic privilege, and the assertion of a universal right of exit, he could laugh at its excesses while respecting and reporting out its various mutations. Wolfe's is a world characterized by what later writers have identified as "bourgeois equality" (Deirdre McCloskey), "plenitude" (Grant McCracken), and "cultural proliferation" (me). It is individualism on steroids—or maybe on poppers, bio-dynamic wine, and grass-fed elk—but it also traffics in new ways of community, from the libertarian communalism of Whole Foods to the blockchain fantasies of your friendly neighborhood cypherpunk. Amid the breakdown of old institutions, modalities, and coalitions ranging from the Republican and Democratic Parties to NATO to old-line churches to broadcast media, we won't be changing addresses anytime soon.

For all the problems of the world that Wolfe mapped for us, it is not only vastly preferable to what came before it—go ask your ditch-digger grandpas and piece-work grandmas if they lived fulfilling lives—it is fantastically more interesting and promising too. Tom Wolfe was the Amerigo Vespucci of our time and, like all important dead people, he will be forgotten even as we still elaborate the maps he drew for us long ago.

Show Comments (21)