California Town Hired Private Law Firm to Sue Citizens, Then Tried to Conceal Massive Costs

Fontana called them "zoning fees." They were actually demanding that residents repay the cost of prosecuting them for minor crimes.

Peter Nolopp, now 79, pleaded guilty seven years ago to renting land for an illegal scrapyard. He paid a fine—$1,000—and cleaned it up. Three years later, the California city of Fontana sent him a bill demanding $29,000 to recoup the cost of his own prosecution.

$24,000 of that were listed as "zoning fees." In fact, they were legal fees billed by a private law firm, Silver & Wright, that Fontana had contracted to prosecute cases for the city.

Fontana is the third California desert town now known to have used this firm to prosecute nuisance cases and code violations, then turn around and demand thousands of dollars from citizens months—even years—after they settle. Desert Sun reporter Brett Kelman has previously exposed the cities of Indio and Coachella for their connections with Silver & Wright; the Institute for Justice and the law firm O'Melveny & Myers are now suing Indio to stop what they're calling a "for-profit prosecution scheme."

Here's how it works. People plead guilty to code infractions—having a messy yard, keeping illegal chickens, adding unpermitted home improvements—and agree to pay modest fines. They say they are not told that this agreement exposes them to demands for additional fees to recoup the cost of their own prosecution, and that these fees are not reviewed by a judge. Instead they receive bills much later for thousands of dollars, complete with threats to put liens on their properties if they don't pay up. And if they attempt to appeal these fees, they are charged additional fees to pay for the cost of the city fighting their appeal.

Kelman reports:

Over the past decade, officials in the city of Fontana have billed residents no less than $43,000 in prosecution fees but classified those debts as unexplained costs or vague "zoning fees." Instead, city records show this money is used to fund the city's privatized prosecutors, the law firm Silver & Wright, which has anchored its business model on making the defendants pay to prosecute themselves. Defendants like Nolopp have said they were unaware they would be billed until after they pleaded guilty, and the billing process occurred entirely outside of the courtroom, so the amounts were never reviewed or approved by a judge.

Additionally, Fontana collected $35,000 through "civil compromises," which are legal agreements in which prosecutors dismiss minor criminal charges if a defendant pays money to the city in an out-of-court settlement. The majority of this money, more than $28,000, was also used to pay Fontana prosecutors, according to city records.

Kelman further notes that the city documents he examined were vague and incomplete. He was able to determine that Nolopp's "zoning fees" were really legal costs because somebody actually wrote it on the bill. So it's not clear whether other charges to other people labeled "zoning fees" are actually zoning fees or legal fees.

Silver & Wright's work with Fontana may have been part of the firm's origin story. The company was founded in 2013 in the midst the attorneys doing work with the city. It then started advertising this mechanism to other cities in California. The firm's website once promised that it could make a city's code enforcement process "cost neutral or even revenue producing." After the Desert Sun revealed what has happening and the lawsuits started to fly, the firm removed the "revenue producing" bit from the site.

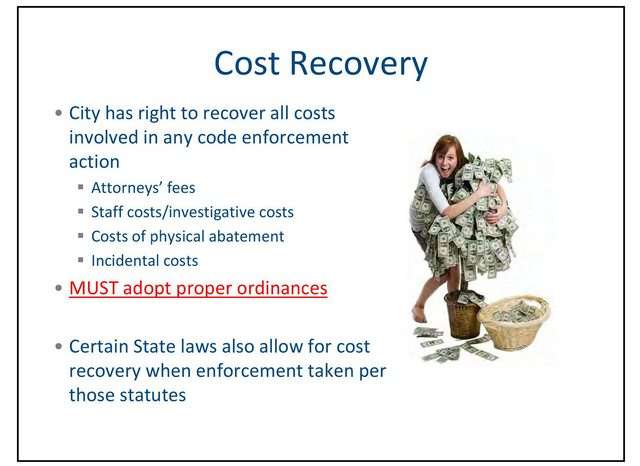

The Institute for Justice has gotten its hands on a PowerPoint presentation the law firm used at a conference to promote its practices to other cities. One slide, titled "cost recovery," features a stock image of a woman overloaded with bundles of cash and an offer that cities can recover all costs of code enforcement, including "attorney's fees." The institute plans to use the slide as evidence of profiteering by the cities and the firm.

In a strange response, Silver & Wright is claiming that the money from these prosecutions actually goes to the city, not to them. It has a contract with the cities and gets paid regardless of whether it gets convictions. Of course, these fees being recovered are for paying Silver & Wright in the first place for a process that the firm itself cooked up and sold to the cities, promising them that they would recoup these costs. So I'm not entirely sure why they think it's a compelling argument.

Show Comments (32)