Experts Agree That Massively Popular Roseanne Reboot Shouldn't Be Popular at All

The only proper popular entertainments are those that conform with my politics, don't you know?

Oh, Roseanne Barr, can you ever win?

Sure, the reboot of your wildly popular and long-lived eponymous 1990s sitcom is a ratings hit, but all the smartest people are acting like you just finished singing the National Anthem at a San Diego Padres game circa 1990. Or dressing up like Lady Hitler and burning cookies. Or pushing Pizzagate, the most-batshit-crazy Hillary Clinton conspiracy theory of them all. Or recovering memories that your parents molested you and then retracting them.

How can you come from low-class roots, become massively successful in show biz, and then be pro-Donald Trump and pro-abortion at the same time? It just doesn't make sense, say all the smartest pundits in the country and at least one of your former co-stars? Can't you see that you're tearing us apart! It's not news that real-life Roseanne, who ran for president herself back in 2012 with anti-war activist Cindy Sheehan as veep, is a Trump supporter, but the shock of someone being funny on network television and playing an unapologetic, unironic Trumpista at the same time is just too much for some of us to bear. To paraphrase Nixon, we're all snowflakes now.

But who gave you the right, the person who popularized the once-ironic term domestic goddess before it was glammed up by Nigella Lawson and before being down-classed by Charlie Sheen, to be messing with our social-political-cultural categories yet again?

Here's Roseanne's case for The Donald over Hillary Clinton way back in June 2016:

I like Trump because he financed his own [campaign]. That's the only way he could've gotten that nomination. Because nobody wants a president who isn't from Yale and Harvard and in the club. 'Cause it's all about distribution. When you're in the club, you've got people that you sell to. That's how money changes hands, that's how business works. If you've got friends there, they scratch your back and blah, blah….To me, he's saying that the order of law matters. When a president can just pass laws all on his own, that is a little bit different than [Trump's] saying what America was supposed to be about. And Trump is saying people will have to be vetted, we'll have to have legal immigration. It's all a scam. I mean, illegal immigration. When people come here and they get a lot of benefits that our own veterans don't get. What's up with that?

What's up, indeed? Roseanne has called herself a socialist at various points, by which she seems to mean a redistributionist rather than a latter-day Rosa Luxemburg, but she also has long trafficked in populist sentiments too. In her new sitcom, her titular character avers that Trump won the election because he at least talked about jobs. Her character and real-life counterpart, like most Americans, are finding fewer and fewer touch-points with traditional political categories of Republican and Democrat, conservative and liberal. I don't presume to understand, much less agree, with Roseanne's political or comedic agenda but the plain fact is she's connecting with contemporary audiences and voters precisely because she no longer feels constrained by two political parties that have been around since before the Civil War. Roxanne Gay, who says she won't continue viewing the reboot even as she admits to laughing during its first two episodes, says that Roseanne's views are "muddled and incoherent." Which is to say they are merely reflecting new possible groupings in the body politic. Why shouldn't there be a political party that is pro-abortion and pro-lower taxes, say? Or pro-free trade and pro-union? Anti-war and anti-immigrant?

I'm not arguing for any of those particular configurations, I'm simply stating that the conventional groupings we've inherited and revised endlessly from the mid-1960s on are pretty much as played out as the Comstock Lode. As political scientist Morris P. Fiorina writes in Unstable Majorities, the political groupings pushed by party activists and media elites can no longer cobble together sustainable coalitions that can hold power for extended periods of time. Those coalitions, after all, were created for very different times and places (the Cold War, for instance, and before Japan and China emerged as economic powerhouses).

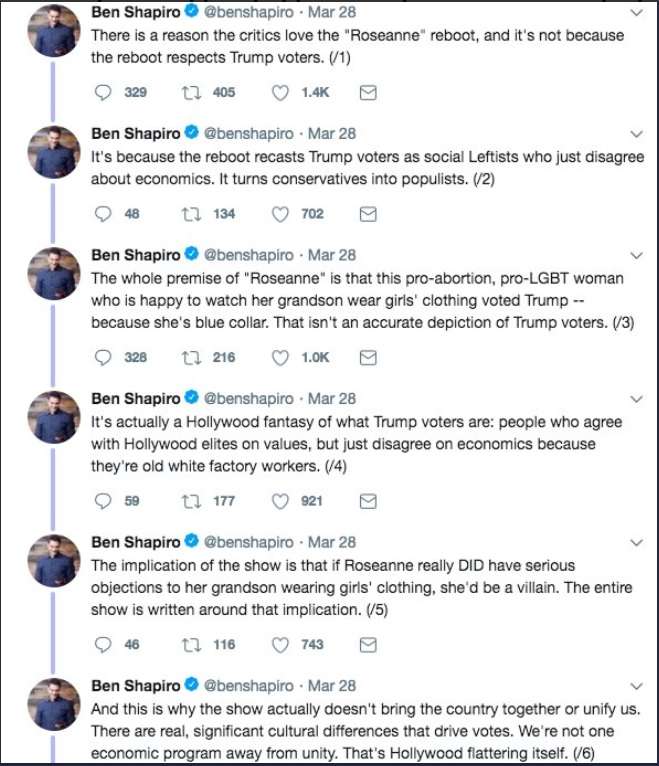

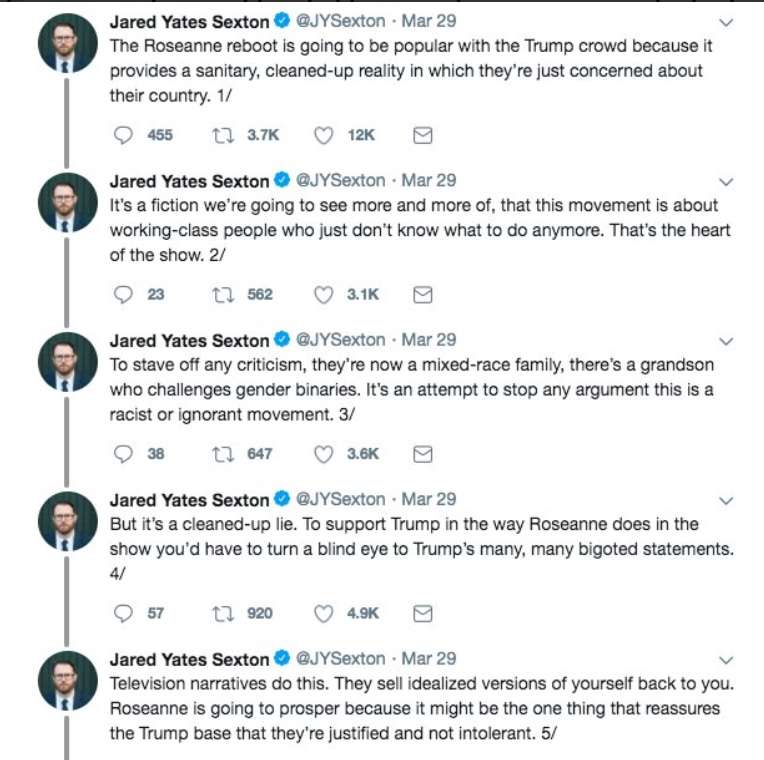

The results of our faltering political coalitions also include an incapacity for trenchant cultural criticism from conventional right- and left-wing perspectives. In the end, what we get instead of explanations of why the Roseanne reboot might be popular are castigations of its popularity. On Twitter, author and television writer Daniel Radosh (follow him!) posts threads from lefty professor Jared Yates Sexton and conservative wunderkind Ben Shapiro and shrewdly observes, "Fascinating that these two completely agree with each other on everything about Roseanne except which side it's propaganda for":

On a slightly different axis, Matthew Continetti of The Washington Free Beacon, casts Roseanne (real-life and fictional) as "the type of swing voter who decides elections." Democrats, he avers, are failing "the Roseanne Test," by talking about immigration instead of health-care costs. Republicans can lose the midterms and more if they reject Roseanne (real-life and fictional) as not worth the trouble of courting when ballots are being counted.

Well, sure. But partisans rarely step away from political tribalism. As fewer people consider themselves Rs or Ds, those that remain (or carry their water in the press) tend to get more and more emphatic that only true believers need apply. There's a reason that Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) is retiring and it's not because the observant Mormon, reliable tax-cutter, believer in fiscal responsibility, and reliable-if-reluctant supporter of military action is way out of line with GOP sensibilities. It's because he colors outside the lines when it comes to a few issues (such as immigration reform and trade with Cuba). If the Republican Party casts Flake into the darkness, it's pushing a purity test straight out of medieval catechisms.

Writing at Bloomberg View, former Reason editor Virginia Postrel does what most observers fail to do: She helps to explain why viewers, most of whom presumably don't share Roseanne Barr's love of Trump or belief that John Podesta was molesting children at Comet Pizza, are nonetheless digging her show:

It is a family sit-com, with the fundamental sweetness that typifies that genre. Its politics are the politics of recognition and empathy. It belongs not with Fox News but with ABC's other family comedies, including "Black-ish," which enjoyed a big ratings boost from its powerful, new lead-in, and "Fresh Off the Boat."…

Most Americans aren't blue-collar midwestern whites, affluent West Coast blacks, or Taiwanese immigrants living in Orlando. But most do have families and enjoy a laugh. The radical premise of "Roseanne"—and of these family sit-coms—is that recognizing diverse viewpoints and voices, including those that don't assume that what we take for granted is the norm, can in fact showcase the things we share. What we have in common is at least as important as what divides us.

We are flocking (so far) to Roseanne not because of its politics but because it gives us a place where we might actually be able to disagree without declaring total war on one another. The show's original run took place in another deeply divided decade, one in which three presidential elections failed to yield a winner who carried a simple majority of votes, a president was impeached, and a speaker of the House resigned under pressure from his own party. Somehow, the nation not only persisted but thrived economically, technologically, and socially. Crime started dropping and TV, along with all other forms of popular culture, suddenly got great. By the end of the decade, politics had receded from front and center of daily life, even as strong disagreements persisted. The return of Roseanne might be occasion for nostalgia for the decade-without-a-name, but that would be a mistake. What the reboot affords us is the occasion to relearn how we might figure out not just how to disagree with each other but also live with each other. After nearly two decades of increasing vitriol, hate, and contempt for one another, no wonder we're tuning in.

Show Comments (128)