The New Omnibus Is Terrible Because Congress Is Broken

The spending bill is a product of a broken, secretive, centralized legislative process.

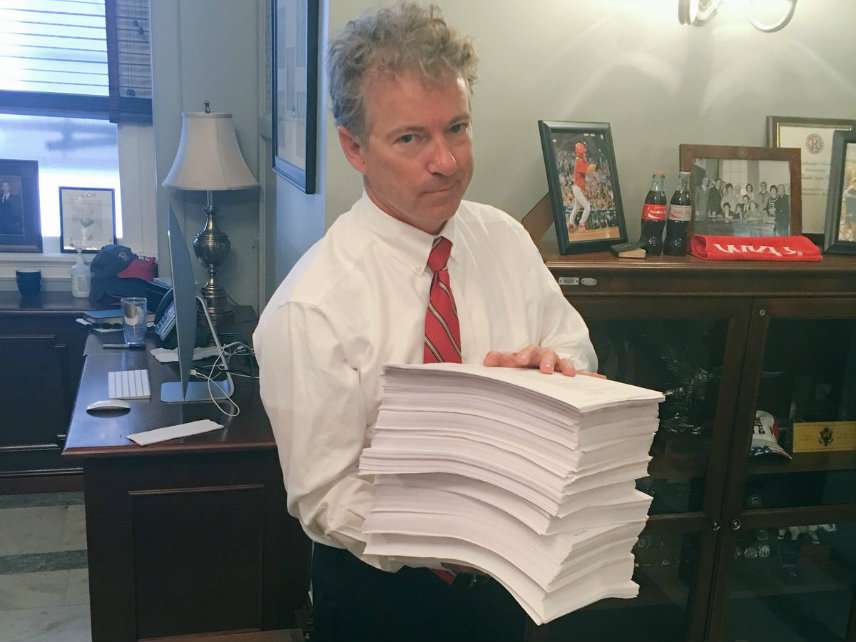

Today, the House is voting on an omnibus spending bill that runs in excess of 2,300 pages. Congress must pass the $1.3 trillion bill by midnight on Friday in order to keep the government open—a deadline that has been known for weeks—but the legislation wasn't released until last night. Until then, the bill was shrouded in secrecy, with no text available to the public or to lawmakers, who had effectively no opportunity to publicly debate its merits, or offer input on its content.

The omnibus is nearly certain to pass anyway. Whether the legislators voting on it like it, or even know what's in it, barely matters.

This isn't unusual. Legislating this way—in secret, at the last minute, with few opportunities for outside input or debate—has become the norm, especially, but not only, when it comes to budgeting.

It's a way of running the government that benefits congressional leadership and their allies at the expense of less powerful lawmakers, and the broader public interest. It means that Congress operates in a state of perpetual low-level crisis, and it breeds dissension and distrust in the entire system. It's one of many bad processes that contributes to unstable policy outcomes and political dysfunction.

In politics, almost no one actually cares about process. When lawmakers do complain about process problems, it's often selective and self-interested. Politicians almost never campaign on process reforms. Talking about process causes voters to tune out. Process is arcane. It's technical. It's arbitrary. It's boring.

But the processes by which the government makes laws, spends money, and implements regulations matter nonetheless. Because effective processes are a way of encoding values—fiscal, political, civil—into a system.

The best government processes are designed to encourage fairness, transparency, openness, inclusivity, and accountability. They offer mechanisms for bringing people of differing views together for respectful and productive debate. They disperse power by offering a forum for minority views. Maintaining good process is important for many of the same reasons that maintaining rule of law is important. A good process does not necessarily ensure an outcome that you want. But it ensures one that all parties involved can accept, at least for the moment.

But today's political leaders don't care about process. And their disinterest has substantive policy consequences.

In December of last year, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell held a late night vote on a draft of the tax reform law just hours after the text was released. Some of the pages were crossed out, and parts of the legislation were handwritten in the margins. At a press conference afterwards, McConnell, however, dismissed complaints about the rushed vote: "You complain about process when you're losing, and that's what you heard on the floor tonight."

In McConnell's cynical worldview, worrying about process is for losers. All that matters is winning.

As it turns out, the tax law was rife with glitches and errors. Restaurants and other retailers were unintentionally denied access to write-offs for business improvements. Another affects the sale of crops to large agriculture businesses. Another makes baseball trades less likely, thanks to the way it affects capital gains taxes. These are just a few examples. The Chamber of Commerce recently compiled 15 pages of questions about how the tax law is supposed to work for companies large and small. The tax law has been a political success. But functionally it's a mess.

Republicans are now attempting to fix some of the mistakes in the law as part of the omnibus, bargaining with Democrats in the process. This is lawmaking at its most depressingly predictable. Republicans want to use one rushed, secretive bill to fix another one.

McConnell also said something else at that late night press conference last year. "I'm totally confident this is a revenue neutral bill." He predicted that the bill, which all expert analysis said would increase the deficit, would actually be a "revenue producer."

He was, of course, wrong. Thanks in part to the tax bill, the deficit is projected to be larger than expected this year, and is now set to top $1 trillion for the first time in years. In an indirect way, this too was an abuse of process, of the expectation of some minimal level of honesty and transparency about legislation. Process is not always about speific rules and procedures. It also about shared norms.

Republican leadership sometimes pays lip service to process concerns. When Paul Ryan became Speaker of the House in 2015, he promised to be less controlling and more transparent than his predecessor, John Boehner. Under his speakership, the House would be "more open, more inclusive, more deliberative, more participatory," he said. "We're not going to bottle up the process so much and predetermine the outcome of everything around here."

Instead, Ryan has run the most closed and centralized House in history, as Politico reported last year. The story is similar in the Senate. When the government shut down briefly in February, it was because McConnell denied Sen. Rand Paul an up or down vote on an amendment that would draw attention to the way the deal broke the federal spending caps put in place under the Obama administration.

Lawmakers in the House have been repeatedly and systematically denied the opportunity to offer amendments to legislation. Legislation is simply presented for up or down vote, with little time to read, process, or debate.

The centralization of power in Congress not a problem that is limited to Republicans. When Harry Reid was majority leader, the Senate ran on a notoriously closed process, one that McConnell promised would change. But Republican leadership holds the power now, and has the responsibility to make changes.

Even many rank and file GOP lawmakers recognize that there's a problem. "I have complete respect for our leadership, but when they foist this on us with less than 36 hours, I think it's very irresponsible," Ted Budd (R–N.C.), said about the omnibus. "Shame, shame. A pox on both Houses—and parties. $1.3 trillion. Busts budget caps. 2200 pages, with just hours to try to read it," tweeted Sen. Rand Paul (R–Ky.).

To be fair, some low-level steps may be in the works. In recent years, the budget process, a series of steps and deadlines that is supposed to happen each year, has broken down. Congress hasn't met all of its deadlines since the late 1990s. That's one of the reasons why short-term spending bills and bloated omnibus spending bills have become the norm. Last month's budget deal created a Joint Select Committee on Budget and Appropriations Process Reform, a bipartisan panel tasked with recommending improvements to the way that Congress goes about crafting annual budget plans by the end of November. The committee's creation has spurred outside groups to offer options for improvement, many of which are worth considering.

But I worry that a committee is just a way of pretending to solve the deeper problem, which is that too many politicians have come to view process as something to be manipulated for short-term partisan advantage rather than as something valuable, and worth preserving, on its own.

It's true, of course, that a better process alone won't ensure better policy. But unlike the rushed, secretive, centralized process that gave us yet another ungainly omnibus, it might at least create the opportunity for change.