Victor Frankenstein Is the Real Monster

Mary Shelley's misunderstood masterpiece turns 200.

Conceived and written 200 years ago by the 19-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley during a dreary summer sojourn to Lake Geneva, Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus is the story of a scientist who, seduced by the lure of forbidden knowledge, creates new life that in the end destroys him.

When the novel debuted, it created a stir for its lurid gothic style and unusual conceit. Early reviewers scolded the then-unknown author, complaining that the slim volume had "neither principle, object, nor moral" and fretting that "it cannot mend, and will not even amuse its readers, unless their taste have been deplorably vitiated."

Yet almost from the moment of its publication, Shelley's narrative has been pressed into service as a modern morality play—a warning against freewheeling scientific experimentation. That reading is pervasive to this day in policy conversations and popular culture alike, cropping up everywhere from bioengineering conferences to an endless string of modern cinematic reboots. There's just one problem with the common reading of Frankenstein as a cautionary tale: It flows from a profound misunderstanding of the original text.

'I Saw and Heard of None Like Me'

In the anonymously published 1818 edition of the book, an adolescent Victor Frankenstein dreams of discovering the elixir of life, imagining "what glory would attend the discovery, if I could banish disease from the human frame, and render man invulnerable to any but a violent death!" Later, enraptured by the study of natural philosophy at the university in Ingolstadt, he devotes himself to the question of whence the principle of life proceeded. "Life and death appeared to me ideal bounds, which I should first break through, and pour a torrent of light into our dark world," he exults.

Frankenstein's arduous study of physiology and anatomy are eventually rewarded by a "brilliant and wondrous" insight: He has "succeeded in discovering the cause of generation and life" and is "capable of bestowing animation upon lifeless matter."

Working alone and in secret, Frankenstein sets about creating a human being using materials gathered from dissecting rooms and slaughterhouses. Because it is easier to work at a larger scale, he decides to make his creature 8 feet tall. (The average height of Englishmen was then about 5 and a half feet.)

After two years of work, Frankenstein on a late night in November ignites "a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet." Although he "had selected his features as beautiful," in that moment he is overcome with revulsion and runs out into the city to escape the "monster" he has brought to life. When Frankenstein slinks back to his lodgings the creature is gone, having taken his coat. Frankenstein promptly succumbs to a "nervous fever" that confines him for several months.

Later we learn that the creature, whose mind was as unformed as a newborn baby's, fled to the woods where he learned to survive on nuts and berries and enjoy the warmth of the sun and birdsong. When the peaceful vegetarian encountered for the first time people living in a village, they drove him away with stones and other missiles.

He found refuge in a hovel attached to a cottage. There he learned to speak and read while observing from his hiding place the gentle, noble manners of the De Lacey family.

The lonely creature comes to realize that he is "not even of the same nature as man." He notes: "I was more agile than they, and could subsist upon coarser diet; I bore the extremes of heat and cold with less injury to my frame; my stature far exceeded their's. When I looked around, I saw and heard of none like me."

The fact that the creature learned to speak and read in a period of just over a year indicates that he is far more intelligent than human beings, too. In any case, he eventually unravels the mystery of his origins by reading notes he finds in the coat he took from Frankenstein.

After even the De Laceys reject him as monstrous, the creature despairs of ever finding love and sympathy. He vows to seek and enact revenge on his creator for his abandonment.

Nearing Geneva some months later, he by chance encounters Frankenstein's much younger brother, William, in the woods. Thinking a child will be "unprejudiced" with regard to his "deformity," the creature seeks to whisk him away as a companion. But the boy cries out, and in an effort to silence him, the creature chokes William to death. He subsequently frames the family servant for his crime, leading to her execution.

When Frankenstein and the creature meet again, the latter justifies his actions on the grounds that all of his overtures of friendship, sympathy, and love have been violently rejected. He then persuades his creator to agree to fashion for him a female companion. Seeking "the affections of a sensitive being" like himself, he vows that "virtues will necessarily arise when I live in communion with an equal." He pledges that he and his companion will lose themselves in the jungles of South America, never to trouble human beings again.

Only after Frankenstein betrays his promise does the creature retaliate by killing all the people closest to his creator. The two eventually perish chasing one another across the ice floes of the Arctic Ocean.

'It's Alive. It's Alive!'

"On the basis of its prevalence in culture, it may be presumed that Frankenstein is one of the strongest memes of modernity," argues the Polish literary critic Barbara Braid in a 2017 essay. "Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is one of the most adaptable and adapted novels of all time, spurring countless renditions in film, television, comic books, cartoons, and other products of popular culture." About 50,000 copies of the book are still sold each year in the United States. According to the Open Syllabus Project, it is the most commonly taught literary text in college courses.

Stephen Jones, in The Illustrated Frankenstein Movie Guide, counts over 400 film adaptations between the Edison Studio's Frankenstein in 1910 and Kenneth Branagh's Mary Shelley's Frankenstein in 1994. There have been at least 15 further Frankenstein-themed movies in the years since. "A complete list of films based directly or indirectly on Frankenstein would run into the thousands," notes University of Pennsylvania English professor Stuart Curran. A new movie, Mary Shelley, starring Elle Fanning, is set to join the cinematic canon this year.

Yet everywhere that Frankenstein's creature goes, he and his creator are misunderstood. Almost without exception, his cinematic doubles are embedded in narratives that depict science and scientists as dangerously bent on an unethical pursuit of forbidden knowledge. That trend was established in the first Frankenstein talkie, in which Colin Clive hysterically repeats "It's alive! It's alive!" at the moment of creation.

It is an idea that has quietly seeped into popular culture in the last 200 years, shaping even those movies and books not explicitly based on Shelley's work. In 1989, University of York sociologist Andrew Tudor published the results of a survey of 1,000 horror films shown in the United Kingdom between the 1930s and the 1980s. Mad scientists or their creations were the villains in 31 percent; scientific research constituted 39 percent of the threats. Scientists were heroes in only 11 percent of the movies.

In 2003, German sociologist Peter Weingart and his colleagues looked at 222 movies and found scientists frequently portrayed as "maniacs" and "unethical geniuses." Scientific discoveries or inventions are depicted as dangerous in more than 60 percent of the storylines. In nearly half, power-hungry scientists keep their inventions a secret. In more than a third, the breakthrough gets out of control; 6 in 10 depict the discovery or device causing harm to innocent people.

The popularity of stories that present uncontrollable, malevolent technology as a threat to humankind shows no sign of abating. Consider how cinematic Frankenstein clones run amok in more recent offerings. In the HBO series Westworld (2016), the android hosts at an amusement park break free of their programming and rebel against their creators. Blade Runner 2049 (2017) depicts a nascent insurrection by bioengineered human "replicants." And Ex Machina (2015) offers a beautiful android, Ava, who kills her designer before escaping into our world.

'Are Pesticides the Monster That Will Destroy Us?'

How did the Frankenstein meme become an avatar for skepticism of scientific experimentation and progress? Largely not because of what Mary Shelley actually wrote. A transmutation began shortly after her novel was published, when hack playwright Richard Brinsley Peake, freely borrowing from the book, wrote and produced his melodrama Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein in 1823. Peake simplified the moral complexity of the story into a gothic parable of hubristic damnation. He also introduced the convention of portraying the creature as an inarticulate beast.

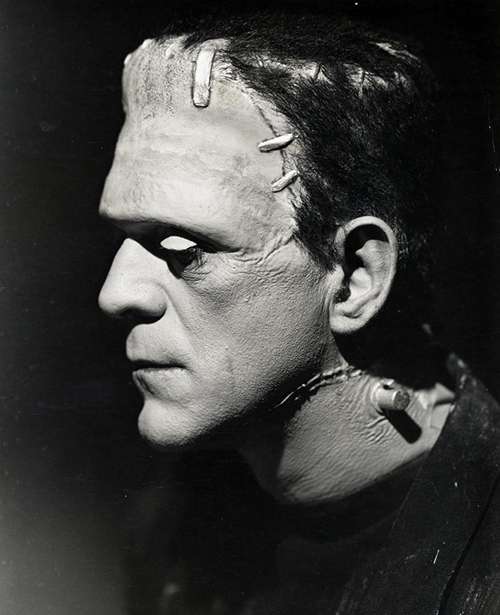

Ever since Peake's wildly popular play debuted, the creature, who eloquently and incisively reproaches the hapless Frankenstein in Shelley's novel, has been silenced. The culmination of this trend was, of course, the iconic 1931 James Whale film in which Boris Karloff played the creature as a neck-bolted, square-headed mute.

This version of the story has stuck around in part because it's so incredibly useful. The meme of Frankenstein as a mad scientist who unleashed a disastrously uncontrollable creation on the world has been hijacked by anti-modernity, anti-technology ideologues to push for all manner of bans and restrictions on the development and deployment of new technologies.

"The mad scientist stories of fiction and film are exercises in antirationalism," argued University of South Carolina anthropologist Christopher Toumey in a 1992 article. He points out that stories like Frankenstein "thrill their audiences by brewing together suspense, horror, violence, and heroism and by uniting those features under the premise that most scientists are dangerous. Untrue, perhaps; preposterous, perhaps; low-brow, perhaps. But nevertheless effective."

Technophobic zealots cannily wield Peake's reimagining of the novel as a rhetorical club with which to bash innovations not just in biotech but in artificial intelligence, robotics, nanotechnology, and more.

After the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, New York Times military analyst Hanson W. Baldwin warned in Life magazine that as soon as such weapons could be attached to German missiles, mankind would have "unleashed a Frankenstein monster." Reviewing Rachel Carson's 1962 anti-pesticide philippic Silent Spring, the Jamaica Press wondered, "Chemical Frankenstein: Are Pesticides the Monster that will destroy us?"

As threatening as nuclear explosions and chemical poisons might be, the Frankenstein meme exerts its greatest rhetorical power when deployed against scientists who study living creatures. As such, science writer/scholar Jon Turney deemed Frankenstein "the governing myth of modern biology" in his 1998 book, Frankenstein's Footsteps: Science, Genetics, and Popular Culture. The Franken- prefix is often used to stigmatize new developments.

"Ever since Mary Shelley's baron rolled his improved human out of the lab," wrote Boston College English professor Paul Lewis in a 1992 letter to The New York Times, "scientists have been bringing just such good things to life. If they want to sell us Frankenfood, perhaps it's time to gather the villagers, light some torches and head to the castle."

In fact, the anti-biotech "Pure Food Campaign" used the premiere of 1993's Jurassic Park to protest the development of the first commercially available genetically engineered tomato. The activists didn't light torches, but they did picket 100 theaters showing the film while passing out fliers that depicted a dinosaur pushing a grocery basket labeled "Bio-tech Frankenfoods."

In that movie, biotechnologists use cloning to bring dinosaurs back to life. "Our scientists have done things which nobody's ever done before," venture capitalist John Hammond explains to mathematician Ian Malcolm. "Yeah, yeah, but your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn't stop to think if they should," retorts Malcolm. Unsurprisingly, the ingeniously created beasts proceed to escape their enclosures and wreak devastation across the land.

When Jurassic Park came out 25 years ago, few scientists thought it would be possible to use biotechnology to bring back extinct creatures. While it remains unlikely that dinosaurs will ever be resurrected, researchers such as Harvard's George Church are working to bring back species including wooly mammoths and passenger pigeons. Last year, Church said his group may be as little as two years away from engineering a mammoth embryo by modifying an Asian elephant genome. The California-based Revive & Restore project estimates that engineered passenger pigeon look-alikes could hatch in 2022.

Such "de-extinction" efforts have their detractors. Deploying the Franken-meme, University of California, Santa Barbara ecologist Douglas McCauley warns of "Franken-species and eco-zombies." In a 2014 essay, Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich suggests that would-be "resurrectionists have been fooled by a cultural misrepresentation of nature and science…traceable perhaps to Mary Shelley's Frankenstein." While Ehrlich's chief fear is that de-extinction efforts will divert resources from conserving still extant species, he also warns that resurrected organisms could become pests in new environments or vectors of nasty plagues.

Yet all these fears are mild compared to the vitriol that arises in response to experiments involving human life.

'A Matter of Morality and Spirituality'

"The Frankenstein myth is real," asserted Columbia University psychiatrist Willard Gaylin in a March 1972 issue of The New York Times Magazine. A successful frog cloning experiment had been recently completed in the U.K., and he believed human cloning was now imminent. As a co-founder of the Hastings Center, the world's first bioethics think tank, Gaylin and his musings caught the public's attention.

His alarm was not confined only to cloning, however; he also warned that researchers were about to perfect in vitro fertilization (IVF), which would enable prospective parents to select the sex and other genetic traits of their progeny. Artificial insemination, though still controversial, was by this time fairly common—the first successful birth from frozen sperm was achieved by American researchers in 1953—but this would take things a big step further.

Infertile women would soon be able to bear children, Gaylin said, using eggs donated from other women. Furthermore, he speculated darkly, a professional woman, out of "reasons of necessity, vanity, or anxiety, might prefer not to carry her child," and such a woman might soon be able to pay another to act as a surrogate. And if an artificial placenta were developed, it would entirely do "away with the need to carry the fetus in the womb."

The creature, who eloquently and incisively reproaches the hapless Frankenstein in Shelley's novel, has been portrayed as an inarticulate beast.

For Gaylin, such biotechnological advances would be fearful transgressions. "When Mary Shelley conceived of Dr. Frankenstein, science was all promise," he wrote in his New York Times Magazine piece. "Man was ascending and the only terror was that in his rise he would offend God by assuming too much and reaching too high, by coming too close." But after two centuries of heedlessly pursuing technological prowess, he said, the "total failure" of the human project could be nigh.

Gaylin expressed hope that researchers would resist the temptation to cross certain lines. "Some biological scientists, now wary and forewarned, are trying to consider the ethical, social and political implications of their research before its use makes any contemplation of its use merely an expiating exercise," he wrote. "They are even starting to ask if some research ought to be done at all."

In 1973, biologists Herbert Boyer of the University of California at San Francisco and Stanley Cohen of Stanford University announced that they had developed a technique enabling researchers to splice genes from one species into another. But instead of pushing forward with this breakthrough, scientists adopted a voluntary moratorium on recombinant DNA research.

In February 1975, 150 scholars and bioethicists gathered at the Asilomar conference center in Pacific Grove, California, to devise an elaborate set of safety protocols under which gene-splicing experimentation would be allowed to proceed. Even so, when Harvard University researchers announced in 1976 that they were about to initiate genetic engineering experiments, the mayor of Cambridge, Massachusetts, declared that the City Council would hold hearings on whether to ban them.

"They may come up with a disease that can't be cured—even a monster," Mayor Alfred Vellucci warned. "Is this the answer to Dr. Frankenstein's dream?" A worried Council imposed two successive three-month moratoria on recombinant DNA experiments within the city limits.

Fortunately, in February 1977, the body voted to allow the research to proceed, despite Mayor Vellucci's continued opposition. Today there are more than 450 biomedical companies headquartered in and around Cambridge; the city is at the center of the largest cluster of life sciences firms in the world.

But that was hardly the death of the controversy. Twenty-five years after Gaylin raised his alarm, fearmongering over human cloning revved into high gear once again.

On February 22, 1997, Scottish embryologist Ian Wilmut announced that his team had succeeded for the first time in cloning a mammal—a sheep named Dolly. Official reaction was swift. On March 4, President Bill Clinton held a televised press conference from the Oval Office to warn mankind that it might now be "possible to clone human beings from our own genetic material." Adding that "any discovery that touches on human creation is not simply a matter of scientific inquiry, but is a matter of morality and spirituality as well," Clinton ordered an immediate ban on federal funding for human cloning research.

The revulsion Victor Frankenstein felt upon sparking his creature into life caused him to reject the being, eventually driving it to a murderous existential crisis. With the news of Wilmut's success, the conservative bioethicist Leon Kass echoed and endorsed Frankenstein's disgust and fear. In a June 1997 New Republic essay, he acknowledges that "revulsion is not an argument" but immediately asserts that "in crucial cases, however, repugnance is the emotional expression of deep wisdom, beyond reason's power fully to articulate it." Like Gaylin, he warns that human cloning would "represent a giant step toward turning begetting into making, procreation into manufacture."

Here again, Mary Shelley's monster rears his head. Ultimately, writes Kass, such biomedical advances would be misbegotten endeavors epitomizing a "Frankensteinian hubris to create human life and increasingly to control its destiny."

'How Many Poor People Must Die?'

Since 1972, many of the supposedly Frankensteinian technologies predicted by Gaylin and others have been perfected. For the most part, they are are widely accepted.

In July 1978, the first "test tube baby," Louise Joy Brown, was born in the United Kingdom thanks to in vitro fertilization techniques developed by embryologists Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe. In April 2017, the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology reported that more than 1 million children have been born in the United States alone via IVF. Across the world, the number is nearly 7 million.

Just as Gaylin feared, some women today do use egg donors, and paid surrogacy is no longer unheard of. Parents can use pre-implantation genetic diagnosis to select embryos for traits, such as sex, or the absence of genetic diseases, such as early onset Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, and cystic fibrosis.

No human clones have yet been born, nor are artificial wombs currently available. But in April 2017, researchers at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia announced that they had managed to keep a premature baby lamb alive for several weeks inside a device they call a "Biobag." The ban on federal funding for human cloning still stands, but privately supported research has not been outlawed.

One of the conveners of the Asilomar conference was James Watson, a co-discoverer of the double-helix structure of DNA, for which he won the Nobel Prize along with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins in 1962. In a 1977 interview with the Detroit Free Press, he looked back on the rush to regulate nascent genetic engineering with some regret. "Scientifically, I was a nut," he said. "There is no evidence at all that recombinant DNA poses the slightest danger."

Today, the Super Science Fair Projects company will sell you a Microbiology Recombinant DNA Kit for just $77. It's labeled as appropriate for ages 10 and up.

Forty-five years after Boyer and Cohen's first gene-splicing experiments, bioengineers have gifted us with a cornucopia of effective new pharmaceuticals, biologics, vaccines, and other treatments for cardiovascular ailments, cancers, arthritis, diabetes, inherited disorders, and infectious diseases. It is impossible to tell for how many years the regulations stemming from the Asilomar conference delayed these developments, but there can be no question the delay was real.

Despite scientifically absurd and mendacious activist campaigns targeting "Frankenfoods," agricultural researchers have created hundreds of safe biotech crop varieties that yield more food and fiber by resisting disease and pests. The adoption of bioengineered herbicide-resistant crops has enabled farmers to control weeds without having to plow their fields, contributing to a 40 percent reduction in topsoil erosion since the 1980s, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Twenty-two years after commercial biotech crops were introduced, they are now grown on nearly 460 million acres in 26 countries. A 2014 review published in the journal PLOS One by a team of German researchers found that the global adoption of genetically modified (G.M.) crops has reduced chemical pesticide use by 37 percent, increased crop yields by 22 percent, and increased farmer profits by 68 percent. Every independent scientific organization that has evaluated these crops has found them safe to eat and safe for the environment.

But activist campaigns are still cowing regulators into denying poor farmers in developing countries access to modern G.M. crops. Activism is also slowing the introduction of a panoply of new enhanced plants and animals. These include crop varieties bioengineered to resist drought and pigs bioengineered to grow faster using less feed.

Opposition to these developments has cost lives numbering in the millions. Vitamin A deficiency causes blindness in between 250,000 and 500,000 children living in poor countries each year, half of whom die within 12 months, according to the World Health Organization. To address this crisis, rice containing beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, was developed. A study by German researchers in 2014 estimated that activist opposition to the deployment of this "golden rice" had resulted in the loss of 1.4 million life-years in India alone.

An open letter signed by 100 Nobel laureates in June 2016 called upon Greenpeace "to cease and desist in its campaign against Golden Rice specifically, and crops and foods improved through biotechnology in general." "How many poor people in the world must die," the laureates pointedly asked, "before we consider this a 'crime against humanity'?"

'I Was Benevolent and Good; Misery Made Me a Fiend'

For decades, the specter of Frankenstein's monster has been invoked whenever researchers report dramatic new developments, from the use of synthetic biology to build whole genomes from scratch to the invention of new plants and animals that can better feed the world. Experiments in repairing defective genes in human embryos, which have been conducted in China and the U.S., are routinely described as precursors to the creation of "Frankenbabies"—the long-dreaded but not yet seen "designer babies."

The transhumanist movement offers another way to think about Frankenstein's creature—as an enhanced post-human. After all, he is stronger, more agile, better inured to extremes of heat and cold, able to thrive on coarse foods and recover quickly from injury, and more intelligent than ordinary human beings.

There is nothing immoral in Frankenstein's aspiration to "banish disease from the human frame, and render man invulnerable to any but a violent death." The people who will choose to use safe enhancements to bestow upon themselves and their progeny stronger bodies, more robust immune systems, nimbler minds, and longer lives will not be monsters, nor will they create monsters. Instead, those who seek to hinder the rest of us from availing ourselves of these technological gifts will rightly be judged moral troglodytes.

Despite the din raised by anti-technology ideologues and the claque of conservative bioethicists, our world is not filled with out-of-control Frankensteinian technologies. While missteps have occurred, the openness and collaborative structure of the scientific enterprise encourages researchers to take responsibility for their findings. During the past 200 years, scientific research has indeed poured "a torrent of light into our dark world." At nearly every scale, technological progress has given us greater control over our fates and made our lives safer, freer, and wealthier.

Victor Frankenstein variously condemns his creature as a "demon," a "devil," and a "fiend." But that is not quite right. "My heart was fashioned to be susceptible of love and sympathy," the creature insists. "I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend." He was endowed with the capacity for hope, sharing the same moral faculties and free will exercised by human beings.

Frankenstein is not a tale about a mad scientist who looses an out-of-control creature upon the world. It's a parable about a researcher who fails to take due responsibility for nurturing the moral capacities of his creation. Victor Frankenstein is the real monster.

In 1972, Gaylin lamented that "the tragic irony is not that Mary Shelley's 'fantasy' once again has a relevance. The tragedy is that it is no longer a 'fantasy'—and that in its realization we no longer identify with Dr. Frankenstein but with his monster."

That is just as it should be.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Victor Frankenstein Is the Real Monster."