Are Health Advocates Finally Wising Up About the Nature of Risk?

Everything we do entails risk. The question is our tolerance for it.

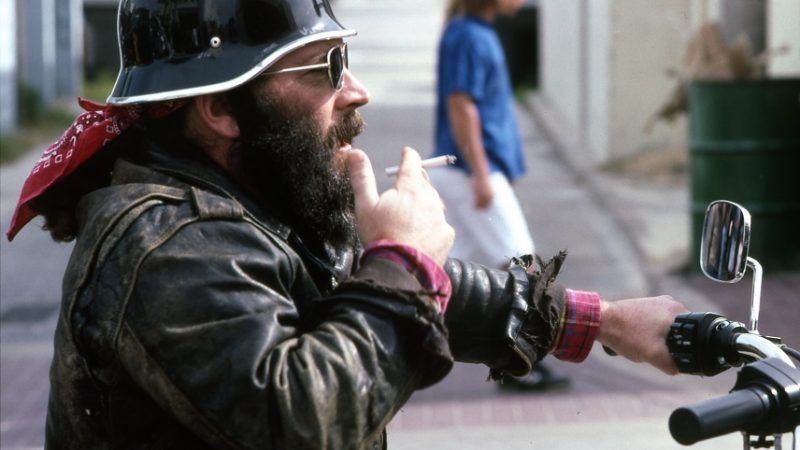

Not to be outdone by a friend who is having his mid-life crisis, I've been going through my own way-past-mid-life crisis. So I've been looking into motorcycle riding as a way to spark a little everyday excitement, which has naturally led to some reading and research about risk—and the amount of it that people are willing to endure.

It's a fascinating topic. Every year, the Isle of Man—a self-governing British dependency in the Irish Sea—hosts a motorcycle race that zooms through the island's gnarled, twisting roadways. Competitors in the Tourist Trophy are routinely killed, with the total death count on the Snaefell Mountain Course hitting 255. It's amazing reading accounts of this risky contest.

I doubt that Americans would tolerate such a dangerous spectacle. But we do accept everyday activities that have a high body count. Nearly 89 Americans die each day in car crashes. And 13 motorcyclists are killed in the U.S. daily on top of that, but risks for bikers are far higher when one factors in vehicle-miles traveled. Motorcyclists account for only 0.6 percent of the miles traveled yet riders account for 21 percent of all vehicle fatalities, according to the National Motorcycle Institute. Bikers are 38 times more likely to die in an accident than people in cars.

Those figures—and anecdotal stories of riders clobbered by birds or killed after some "cager" on a cellphone cuts in front of them—ultimately put the kibosh on my thoughts of taking weekend motorcycle rides through the Sierra foothills. But others are more willing to accept the risk. And there's still plenty of risk that non-riders face on any given day. I have two friends who have been hit by cars while walking just in the past year.

That brings me to the topic at hand: tobacco use. The statistics are even more daunting than those involving motorcyclists. The Centers for Disease Control blames cigarette smoking for 480,000 deaths in the United States per year. Even if those figures are inflated, that's still a shockingly high number. All these fatality numbers, by the way, are dwarfed by the injury and sickness numbers. I'm far more willing to risk death than I am willing to risk spending the next year in the intensive-care unit, or spending my golden years eating through a feeding tube.

Policy makers are understandably intent on reducing risks wherever possible. Road safety groups are understandably intent on improving vehicle safety in a variety of ways (Anti-lock braking systems on motorcycles, for instance, are viewed as a great safety improvement). Anti-tobacco groups are understandably intent on convincing more Americans to give up a deadly habit. Smoking rates are down thanks in part to some public policies, but a certain level of zealotry has hobbled efforts to make even greater strides in reducing the number of tobacco-related deaths.

Several California localities have passed bans on flavored tobacco products (menthol cigarettes, cheap flavored cigars, etc.) as a way to limit their appeal, especially to teenagers who might be tempted to try them. Unfortunately, the bans always include flavored electronic cigarettes. Because virtually all vaping liquids are flavored, that means a ban on a product that isn't risk-free—but is far less risky than combustible cigarettes. State officials have foolishly insisted that vaping is just another form of smoking and should be treated in the same harsh manner.

But perhaps we're finally seeing a more sensible, less ideological approach to tobacco risk take hold among health advocates who are committed to reducing the death rate associated with cigarettes. For instance, this month the American Cancer Society, which had previously avoided recommending vaping, issued a statement that is worth applauding.

The society supports "FDA-approved cessation aids" and recommends that people give up all tobacco products. That's nothing new, but it also included this sensible advice: "Many smokers choose to quit smoking without the assistance of a clinician and some opt to use e-cigarettes to accomplish this goal. The ACS recommends that clinicians support all attempts to quit the use of combustible tobacco and work with smokers to eventually stop using any tobacco product, including e-cigarettes." It also calls for more FDA research. That's progress.

There are two different ways to deal with risk, from a policy standpoint. One is to insist on abstinence. That approach has dominated regulations toward tobacco, especially in California with its Nanny State mindset. The other—known as "harm reduction"—accepts that people do dangerous things, but helps them make safer choices.

Everything we do entails risk. The question is our tolerance for it. Mine is fairly low, so I'll probably pursue my latest life crisis on a 10-speed bicycle rather than a 900cc Ducati. And I'm not about to start smoking cigarettes. But those who do smoke need fewer bans and less hectoring—and more access to products such as e-cigarettes that might save their lives.

This column first appeared in the Orange County Register.

Show Comments (20)