Pennsylvania's New Congressional Districts Are More Compact. But They're Still Just as Partisan.

The state Supreme Court did away with a Republican gerrymander and tilted the new map toward Democrats. That should be worrying.

Democrats got a boost in their effort to retake Congress this week, as the Pennsylvania Supreme Court unveiled a new congressional district map to replace a Republican gerrymander the same court had ruled unconstitutional last month.

The new map imposed by the court is undoubtedly less gerrymandered than the previous one, which has been drawn by Republican state lawmakers after the 2010 census. The GOP had won 13 of Pennsylvania's 18 congressional seats in each of the three elections held under that map. The new map will, according to a variety of analyses released this week, lend itself to a more balanced division of the state's congressional delegation.

The new map also features districts that are more compact. The "compactness" of congressional districts can be measured in several different ways—for example, by measuring the size of the smallest circle that can be drawn to encompass the entire district—but the Supreme Court map improves on the old Republican map pretty much any way you slice it.

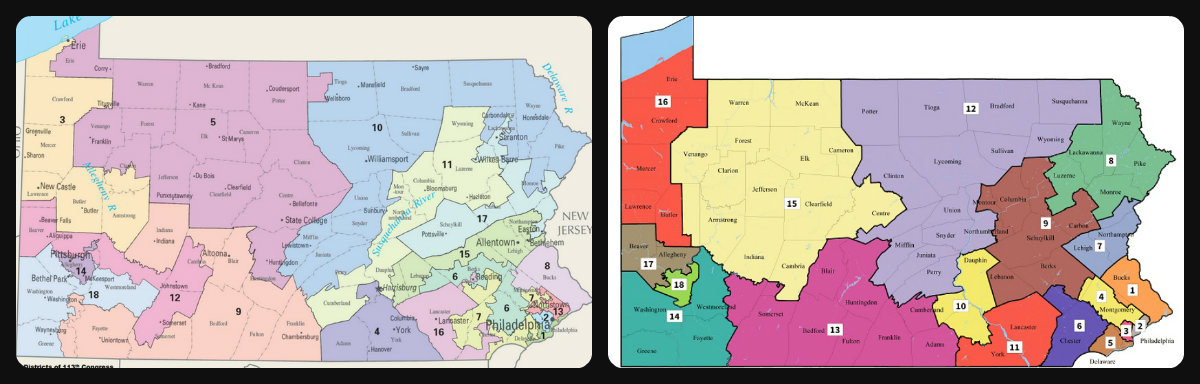

Even without engaging in complicated geometry, that much is plain just by looking at the two maps side by side. The 2011 map is on the left; the court-drawn map is on the right:

Gone are the awkward tentacles and interweaving of districts in the Philadelphia suburbs. Instead we see districts that (mostly) follow county lines.

Rather than simply undoing the Republican gerrymanders, though, the state Supreme Court map may tilt things slightly in the Democrats' favor.

"This is the PA map Dems wanted," tweeted Dave Wasserman, U.S. House editor for The Cook Political Report. "It's a ringing endorsement of the 'partisan fairness' doctrine: that parties should be entitled to same proportion of seats as votes. However, in PA (and many states), achieving that requires conscious pro-Dem mapping choices."

To understand why, you have to know a few things about Pennsylvania. The state has about a million more registered Democrats than registered Republicans, but because blue voters are clustered in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and a few other places around the state, Republicans have a natural advantage when it comes to congressional districts. In other words, even without too-clever-by-half district lines like the ones they drew in 2011, Republicans would be favored to win probably 10 or 11 of the state's 18 seats on a generic ballot in a non-wave election.

The bottom line: If you overlay this new map onto precinct-level election results in 2012 and 2016, and you'd expect Democrats to win seven or eight seats, instead of just five. With a bit of a wind at their backs, Democrats could win up to 11.

The result: Dems have a great shot to win 8-11 of PA's 18 seats in November. Under a truly partisan-blind compact map, maybe 7-10. Under old GOP map, maybe 6-9.

— Dave Wasserman (@Redistrict) February 19, 2018

Republicans pushed the envelope in 2011. It worked, until it didn't. (Republicans hold a 12-5 edge at the moment, with one open seat that will be filled with a special election on March 13. Confusingly, that election will be held within the lines of the now-trashed 18th district as it was drawn in 2011.)

Democrats took control of the state Supreme Court in 2015—judges in Pennsylvania serve in technically nonpartisan role but are elected via a partisan process—and some of the new justices campaigned on a promise to review the Republican-drawn congressional maps if given the chance. When they got the chance, no surprise, they tossed the Republican map and replaced it with their own, Democratic-friendly map.

While the new map is not as blatantly gerrymandered as the 2011 Republican map, it makes a lot of small, subtle choices intended to nudge congressional districts toward the Democrats, as The New York Times' Nate Cohn demonstrates.

The best example of that phenomenon is with the minor changes to the boundary of the current 8th district, which mostly follows the outline of Bucks County, just north of Philadelphia. It was probably the most competitive district in the state under the old map—the old district scores as "even" in Cohn's analysis—but tiny deviations in the western border of the district remove some Republican-heavy portions of neighboring Montgomery County and substitute them with Democrat-heavy areas of the same county. The result is a district that's now slightly favorable to Democratic candidates. (This was already a major midterm target for Dems; now it will be a must-have.)

The lesson in all of this, as National Journal political editor Josh Kraushaar puts it: "You can't take the partisanship out of politics."

Just like other supposedly nonpartisan redistricting efforts, the Supreme Court's creation succumbed to the inherently political nature of congressional mapmaking. Unlike those other attempts to remove politics from the equation, though, this unscheduled redrawing of districts has actually increased the partisanship of the process.

There's a chance the U.S. Supreme Court will review the state court's actions and rule that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overstepped its constitutional bounds by imposing this map without the consent of the state legislature or the governor. Under both the state and federal constitutions, redistricting powers are explicitly granted to state legislators—and even when legislatures have voluntarily tried to pass off that authority to others, they have faced lawsuits for doing so.

If the SCOTUS doesn't block the new Pennsylvania map, the state Supreme Court will have set a dangerous new precedent by scrapping and redrawing congressional districts in the middle of what's supposed to be a 10-year cycle for redistricting. There is literally nothing to stop a Republican judge from seeking the next vacant state Supreme Court seat with promises of undoing this congressional map and imposing a new one. Each new state Supreme Court election in Pennsylvania will come with the implicit (if not explicit) promise of shifting the congressional district lines to favor the winning party.

Gerrymandered district lines disrespect the will of the voters, but so does constantly shifting district lines.

It's difficult to feel bad for the Republicans, who drew a bad-faith map in 2011 and eventually got their comeuppance for doing so. They deserved to lose their ill-gotten advantage. But Democrats do not deserve the advantage they have given themselves by politicizing the state Supreme Court's oversight powers.

Show Comments (106)