Yes, This Is a Good Time To Talk About Gun Violence and How To Reduce It

The Florida school shooting is horrific, but making sure such tragedies never happen is no simple matter.

In the wake of the Florida school shooting that has left 17 dead, politicians who typically promote Second Amendment rights to gun ownership have already gone into a defensive crouch. At a press conference near Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, Gov. Rick Scott, a favorite of the National Rifle Association (NRA) parried away a question about gun control by mumbling platitudes about a "mental health" crisis in America before saying this wasn't a good time to talk about politics.

The reluctance is understandable but ultimately self-defeating and cowardly. While it's true that few things are more reprehensible than the instantaneous politicization of terrible events, it's also true that constantly dodging heartfelt questions about the apparent effects of your policies is neither legitimate nor convincing. Scott's quick invocation of mental illness is weak, as well, especially since one thing we can likely be sure of is that most information about the shooter, identified as 19-year-old former student Nikolas Cruz, will be heavily revised or abandoned completely. Indeed, it turns out that virtually everything most of us still believe about the killers behind the 1999 Columbine school shooting, the incident that dominates our thinking about such events, is wrong. The shooters weren't bullied, they weren't goths or obsessed with video games, and they didn't target minorities or jocks.

If we can't yet confidently say anything about this particular shooting, however, there are still large points we can make and questions we can ask, including the following:

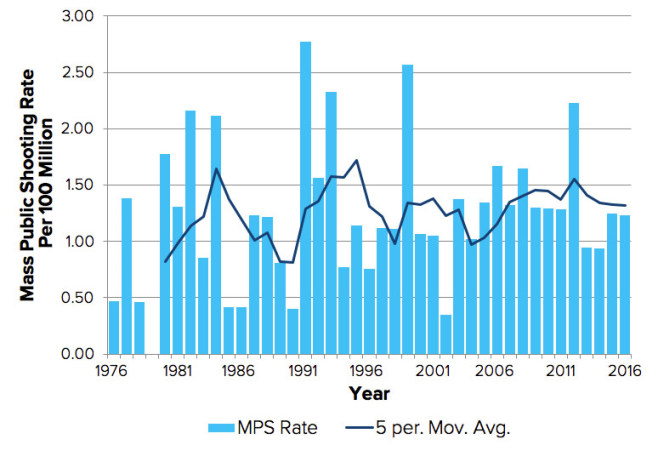

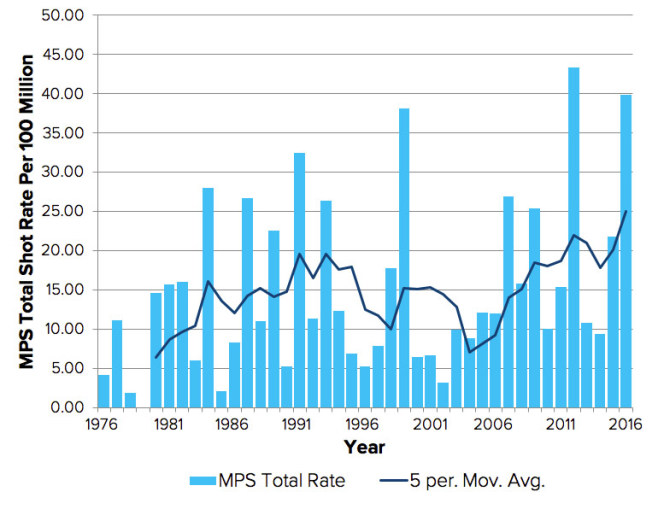

Mass shootings aren't getting more common, but they are getting more deadly. As researcher Grant Duwe wrote in Politico last fall, "What has increased over time is the number of people shot in these incidents. Looking at annual trends in the total number of victims shot in mass public shootings (on a per capita basis), you can see that the severity has recently increased, reaching a 40-year high."

Some people will rush to say this is a distinction without meaning, but surely it means something that there aren't more shootings happening. From a strict cost-benefit analysis of gun control, it might be an argument for changing the sorts of guns that are legally in circulation (though there are plenty of issues with effecting that change; see below), but it also suggests that there isn't some sort of societal breakdown that is causing more and more individuals to become psychopaths.

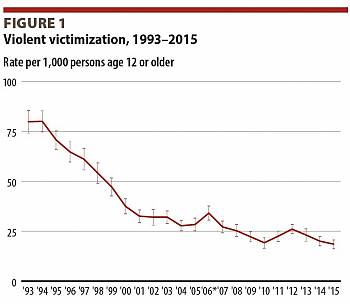

Gun crime and gun violence are still way, way down from 20 years ago. In the wake of last fall's Las Vegas shooting, I wrote, "'From 1993 to 2015, the rate of violent crime declined from 79.8 to 18.6 victimizations per 1,000 persons age 12 or older,' says the Bureau of Justice Statistics in its most recent comprehensive report (published last October, using data through 2015). Over the same period, rates for crimes using guns dropped from 7.3 per 1,000 people to 1.1 per 1,000 people. The homicide rate is down from 7.4 to 4.9. These are not simply good things, they are great things. They are the essential backdrop of all discussions about gun crime and mass shootings, even as we grieve the people killed nonsensically in Vegas."

None of that takes away an iota of the pain and terror of what is still unfolding in Florida, but the most-basic argument for gun control remains that reducing the number of guns in circulation will reduce the amount of gun violence in society. Yet since the mid-1990s, states and localities (and certainly Florida) have mostly made it easier for more people to buy and carry guns in more sorts of situations. The correlation has been with vast reductions in gun crime and gun violence.

All mass shooters are "mentally ill," but defining that term is no easy feat. It seems to me that anybody who shoots up a school or a concert is sick in the head. As Gov. Rick Scott's response suggests, one of the standard disclaimers issued by gun-rights advocates in the wake of a mass shooting is to lament widespread "mental illness" as a way of avoiding thornier questions of what sorts of guns might be restricted under the Second Amendment. The NRA, an inconsistent defender of gun rights at best, typically goes the same way, often calling for broader and broader designations of mental illness that would restrict more and more people from being able to legally own guns. Reason's Jacob Sullum has reported how such laws almost always means virtually unlimited power for mental-health professionals and others to restrict constitutional rights.

When it comes to mass shooters, the efficacy of such policies is even less clear. Reason's Zach Weissmueller noted in 2013,

A recent Mayo Clinic study points out that mass shooters tend to meticulously plan their crimes weeks or months in advance, undermining the idea that the mentally ill simply "snap" and go on shooting rampages while also complicating the notion of effective gun control through gun registries, since a methodical planner has plenty of time to obtain weapons through illegal channels.

A more basic problem with a strategy that targets mentally ill people is that the vast majority of them are not violent. When you control for substance abuse, a factor that exacerbates violence in all populations, only about 4.3% of people with a "severe" mental illness are likely to commit any sort of violence, according to a University of Chicago study. The violence rate among those with a "non-severe" mental illness is about equal to that of the "normal" population.

Broadening the definition of mental illness sounds like an obviously good idea that is actually incredible difficult to implement in any meaningful way. Weissmueller's documentary on the topic explores the problem in depth:

Would restricting certain types of weapons make mass shootings less deadly? It appears the Florida shooter used an "AR-15" style rifle. AR-15 rifles are reportedly the most popular sort of long gun in America and have been used in many mass shootings. Any number of cable-news commentators, including former FBI agents and soldiers, have already made the case that there is no "good" reason for law-abiding people to want such a weapon, particularly if it's a semi-automatic. Such guns, goes this argument, are only good for killing people. Throw in large-capacity magazines and the death toll is going to be larger than it would be with less-lethal weapons. Yet the assault-weapons ban in effect from 1994 to 2004 had essentially no impact on violence, leading researchers to conclude: "Should it be renewed, the ban's effects on gun violence are likely to be small at best and perhaps too small for reliable measurement." "Assault weapons" is a fundamentally meaningless category but the whole point of the ban on such weapons was to remove "military-style" weapons from home collections. But it turns out that rifles in general don't account for much in the way of gun crime and violence. And given that there are already something like 8 million AR-15s in circulation, it's not clear exactly how they would be pulled out of people's homes even if that were a certain way to minimize casualties in mass shootings.

Do strict firearms laws reduce gun deaths? Along with arguing that access to certain types of weapons needs to be restricted, many gun-control advocates on the cable nets are talking about how more gun laws mean fewer gun deaths. Florida has weak gun laws and relatively high numbers of gun deaths, goes this argument, while Massachusetts has strict gun laws and relatively few gun deaths. But as Brian Doherty pointed out in his 2016 feature for Reason magazine, "You Know Less Than You Think About Guns," even the basic correlation behind such an observation is unclear:

"States with strictest firearm laws have lowest rates of gun deaths," a Boston Globe headline then announced. But once again, if you take the simple, obvious step of separating out suicides from murders, the correlations that buttress the supposed causations disappear. As John Hinderaker headlined his reaction at the Power Line blog, "New Study Finds Firearm Laws Do Nothing to Prevent Homicides."

Among other anomalies in Fleegler's research, Hinderaker pointed out that it didn't include Washington, D.C., with its strict gun laws and frequent homicides. If just one weak-gun-law state, Louisiana, were taken out of the equation, "the remaining nine lowest-regulation states have an average gun homicide rate of 2.8 per 100,000, which is 12.5% less than the average of the ten states with the strictest gun control laws," he found.

Public health researcher Garen Wintemute, who advocates stronger gun laws, assessed the spate of gun-law studies during an October interview with Slateand found it wanting: "There have been studies that have essentially toted up the number of laws various states have on the books and examined the association between the number of laws and rates of firearm death," said Wintemute, who is a medical doctor and researcher at the University of California, Davis. "That's really bad science, and it shouldn't inform policymaking."

Wintemute thinks the factor such studies don't adequately consider is the number of people in a state who have guns to begin with, which is generally not known or even well-estimated on levels smaller than national, though researchers have used proxies from subscribers to certain gun-related magazines and percentages of suicides committed with guns to make educated guesses. "Perhaps these laws decrease mortality by decreasing firearm ownership, in which case firearm ownership mediates the association," Wintemute wrote in a 2013 JAMA Internal Medicine paper. "But perhaps, and more plausibly, these laws are more readily enacted in states where the prevalence of firearm ownership is low—there will be less opposition to them—and firearm ownership confounds the association."

The facts of the Florida school shooting haven't yet been established and the motivations of the shooter remain unknown. Given that, there's very little that any of us can say with certainty about what particular law or practice might have prevented or minimized the carnage. Even when all that is known, it's likely that there will have been very little any single person or legislature might have done to prevent such an event without a wholesale change in our open society. That is not a defense of quietism or indifference, but good policy and law-making must acknowledge the limits of government action. What happened in Florida is beyond awful, but it won't be remedied by laws and policies that have chance of achieving their purposes either.

Show Comments (0)