This Is the Time To Defend the Second Amendment and Less-Strict Gun Control

Anti-gun activists are pushing for a crackdown in the wake of the Vegas shooting. That's understandable but wrong.

In the wake of the Vegas mass shooting—the deadliest in U.S. history—anti-gun activists are out in force. "There can be no truce with the Second Amendment" reads a headline at The New Yorker. "How should we politicize mass shootings?" asks The New Republic. "Dear Dana Loesch, shut up" proclaims a piece at Refinery 29 name-checking a prominent spokeswoman for the National Rifle Association (NRA). Late-night talk show host Jimmy Kimmel, who recently made an appeal to maintain or even expand Obamacare, told his audience on Monday, "There are a lot of things we can do about [gun violence]. But we don't."

Who can blame them? Of course Second Amendment defenders (I'm one, despite my visceral unease around guns of any shape or size) say that this isn't the time for an emotion-laden discussion of horrific violence. Shouldn't we resist "the grotesque urge to immediately transform all human tragedies into a political agenda" before we even know what happened, I asked just yesterday. Seven years ago, in the wake of the shooting of Arizona Rep. Gabby Giffords and the instantaneous and erroneous linking of Sarah Palin's bland go-get-em campaign rhetoric to the rampage of a deranged shooter who turned out to be an MSNBC fan, I sounded a similar note, arguing that the "the goddamn politicization of every goddamn —thing not even for a higher purpose or broader fight but for the cheapest moment-by-moment partisan advantage" was one of the major reasons that Americans increasingly hate politics and politicians.

I stand by all that. It's wrong, I think, to immediately pivot to what are inevitably pushed as "common-sense" policy responses to gun attacks, such as banning "assault weapons" (a class of guns that doesn't really exist, have been banned in the past with no impact on violence, and detract from other, arguably more effective regulations). Thoughts of tearing up the Constitution clearly come more from the heart than the head and should be resisted until the passions calm at least a little. If hard cases make bad law, then public tragedies make terrible policy, whether we're talking about mass shootings, acts of terrorism, or celebrity drug overdoses.

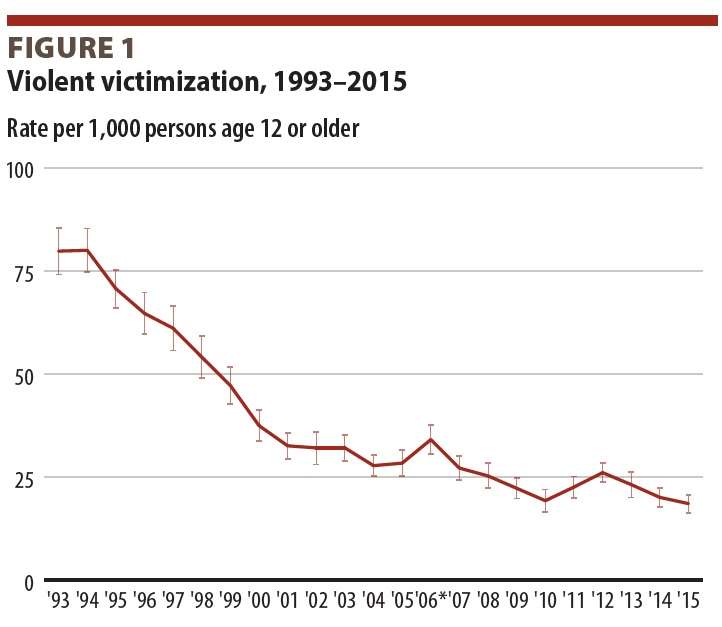

Yet libertarians who believe in their arguments should also advance their case that strong protections for gun owners are a good thing even as we pay condolences to the dead and think about ways to minimize similar events. It's not cold-blooded or Vulcan to point out that we remain in the midst of an unprecedented deceleration of violent crime and gun crime. Surely that has some connection to policies over the past quarter-century or so that have made it easier for a wide variety of people to legally own and carry guns.

"From 1993 to 2015, the rate of violent crime

declined from 79.8 to 18.6 victimizations per 1,000 persons age 12 or older," says the Bureau of Justice Statistics in its most recent comprehensive report (published last October, using data through 2015). Over the same period, rates for crimes using guns dropped from 7.3 per 1,000 people to 1.1 per 1,000 people. The homicide rate is down from 7.4 to 4.9. These are not simply good things, they are great things. They are the essential backdrop of all discussions about gun crime and mass shootings, even as we grieve the people killed nonsensically in Vegas.

By one count, seven of the 15 deadliest mass shootings have occurred in the 21st century alone, despite the fact that it's not even two decades old yet. It is not clear at all whether mass shootings are actually more common than they used to be, although there is evidence that they are more deadly. Last June, after the mass shooting at Orlando's Pulse nightclub, CNN published two charts showing mass shootings to date in 2016. Using an expansive definition that counted all incidents in which four or more people, including the original gunman, were wounded or killed, there had been 136 incidents as of June 21. Using a more restrictive definition that excluded domestic violence and gang incidents, there had been three shootings involving four or more casualties. Partly as a result of such wide parameters, the overall decline in gun violence has gone largely unacknowledged by many people, including Donald Trump, who delusionally campaigned as "the law-and-order candidate" who alone could reverse a non-existent increase in violent crime.

Which of course gets us precisely nowhere as we contemplate the dozens killed and the hundreds wounded on Sunday night in Vegas. Are there policies that might reduce the likelihood of such terrible acts without eviscerating not just constitutional rights but developments that have correlated with a much, much safer America? Perhaps, but they aren't immediately obvious or pragmatic. As Jacob Sullum noted yesterday, most of the ideas pushed by anti-gun activists would have no conceivable impact on mass shooters such as Stephen Paddock. Raising the minimum age for gun purchases to 21, limiting the number or purchases allowed each month, and developing "smart gun" technology have nothing to do with what we know (so far anyway) about Vegas, or virtually any other mass shooting. And the policy prescriptions that might—such as barring individuals with serious, documented mental problems or convictions for domestic abuse—would not have snagged Paddock. Dreams of confiscating the more than 300 million guns in private hands, thus creating a country where only the police (who have their own problems with using firearms responsibly) would require the creation of a police state every bit as bad or worse than the ones implied by The Patriot Act and the nonsensical urge to rid the workplace of illegal immigrants. Gun-control proponents like to point to rigid controls put in place in Great Britain and Australia after mass shootings. But they fail to report that, as scholar Joyce Malcolm writes, "Strict gun laws in Great Britain and Australia haven't made their people noticeably safer, nor have they prevented massacres. The two major countries held up as models for the U.S. don't provide much evidence that strict gun laws will solve our problems."

Denouncing those of us who counsel waiting until all the facts are in before implementing bold new policies whose real effects are often unintended is understandable but misguided (read this about Australia's widely mischaracterized gun-buyback program). Jimmy Kimmel and others who agree with him mean it when they say things such as:

There are a lot of things we can do about [gun violence and mass shootings]. But we don't. Which is interesting, because when someone with a beard attacks us, we tap phones, we invoke travel bans, we build walls. We take every possible precaution to make sure it doesn't happen again. But when an American buys a gun and kills other Americans, then there's nothing we can do about that. Because the Second Amendment. Our forefathers wanted us to have AK-47s, is the argument."

Their anger and sadness, which is heartfelt and shared by everyone I've spoken with, is understandable but it misdirects them. Who exactly are the people clamoring for presumably fully automatic AK-47s, which are already virtually impossible for most people to own, in every home? That's not the argument from the NRA and certainly not from me. And when you start to look at the policies Kimmel and people like him use to justify doing something now, the examples are plainly terrible. It's not a good argument to say that since we are still overreacting to Muslims because of 9/11 and to Mexicans wanting to work in the United States, we should follow suit when it comes to mass shootings.

As a country and as individuals, we need to pay our respects to the dead and wounded in Vegas. But policy cannot be a form of therapy that will neither bind our wounds now nor make us safer in the future.

Related video: "How to create a gun-free America in 5 easy steps" (2015).

Show Comments (121)