Don't Blame Ron Paul for Donald Trump

The guy who launched a movement running for president in 2008 and 2012 was not the guy from the notorious newsletters.

James Kirchick, writing in The New York Review of Books, offers the thesis that Donald Trump and his cause are somehow the fault of Ron Paul, the former Republican congressman from Texas and two-time seeker of the Republican presidential nomination (and one-time candidate of the Libertarian Party, in 1988). Trump, the headline asserts, owes a "Debt to Ron Paul's Paranoid Style."

His bill of particulars connecting Paul and Trump: Kirchick in 2007 "had obtained a trove of newsletters that the libertarian gadfly had intermittently published from the late 1970s through to the mid 1990s, which were chock-full of conspiratorial, racist, and anti-government ravings."

Further, "The ideological similarities between the two men, and the ways in which they created support, are striking." Among them in policy terms are that both men spoke out against entangling military alliances and the notion that we must be relentless foes of Russia; both said things that might appeal to white supremacists; and both in their private careers helped sell things to the public that positioned them as false "guru[s] of personal enrichment." Kirchick, perhaps carelessly, seems to imply that Paul was an Obama birther like Trump, which Paul was not.

At any rate, Kirchick goes on to argue with quoted examples that the strategy of newsletter-era Ron Paul "was to appeal to voters on three bases—racial animus, anti-elitism, and nativism." He rightly notes that Trump's winning campaign in 2016 played to some of the same themes (two of which are pernicious; one, anti-elitism, is not necessarily so).

Kirchick declares that Paul's message "shares the limited government principles of traditional libertarianism but places a heavier emphasis on conservative social values, white racial resentment, and isolationist nationalism." This stew, he notes, fed into a portion (how large a portion Kirchick doesn't pretend to know) of Trump's fan base.

Kirchick's evidence connecting Paul and Trump, then, is the reason many people know James Kirchick's name to begin with: newsletters from the 1983–1996 interregnum between two of his stints as a congressman.

What Kirchick is implicitly saying is that some of the people surrounding Ron Paul in the late '80s and early '90s—people who believed there was political capital to be gained by mixing anti-government ideas with right-populist white resentment—were not the utter loons assumed by most others in the libertarian community, who watched aghast as it happened in real time. In fact, he suggests, they were shockingly prescient. (Kirchick, like nearly everyone, most certainly including me, clearly also underestimated the political power of that toxic brew.)

The gap between Kirchick's evidence and his conclusions, the underappreciated fact that makes this article's causal connection between Paul and Trump fail, is that he doesn't sufficiently stress his own reportorial entrepreneurship. He forgets (or wants the reader to forget) the reason people who hadn't followed Paul closely for most of his career found Kirchick's articles a potentially gamechanging newsbreaker: The Ron Paul who ran in 2008 and 2012 evinced none of those awful qualities that Kirchick highlighted in his reporting on the newsletters (which is why it was easy for most people, supporter and enemy alike, to grant that Paul likely didn't write them in the first place).

I witnessed, both in person and via video, many dozens of hours of Ron Paul campaigning in those years. He did not have a standard stump speech, so I cannot authoritatively state he never said anything bad along those lines. But I never heard them. And that an inveterate Paul enemy such as Kirchick never quotes any either lends weight to the notion that white-backlash right-populist rage of the Trump variety was no part of Ron Paul's presidential campaigns.

That's important to Kirchick's thesis because the only place where Paul had a significant effect on the minds, thoughts, and allegiances of a mass of Americans was as a campaigner. If not for Kirchick's own work, likely fewer than a couple thousand Americans would have any idea that those newsletters even existed, much less any ugly specifics of them. Whatever nasty currents of American thought those newsletters tapped into, they didn't "cause" anything. Ron Paul's presidential campaigns did.

Kirchick's attempt to blame Trump on Paul fails because Kirchick doesn't probe the things Paul actually said as a candidate, that built his mass audience and his millions of votes: his actual influence on America. Before he was a candidate, Paul engaged with unpleasant strains of the American political psyche, strains that Trump proved were far stronger than many of us wanted to know. But "the pre-candidate Ron Paul and Donald Trump tried to appeal to a right-wing nativism that long predated either of them" is not the same as causation or reliance.

Put it this way: I don't see how or why anyone would think Donald Trump wouldn't have been who he was or done what he did (and had the same success) if Ron Paul had never been born. Kirchick himself notes that immigration was "an issue where Paul did not stake out a hard-right stance," as indeed he did not (the one time his campaign ran a right-leaning ad on the topic, not an issue Paul talked about on the stump, it appalled many of his fans); and border wall nonsense was the heart of Trumpism.

But what Ron Paul the presidential candidate was actually transmitting—what he indeed successfully transmitted, as I learned covering him for Reason—was a pretty consistent libertarian message of keeping government force out of individual's lives, at home and abroad.

Here are a couple of telling examples from my reporting on his campaigns, in which I spoke to many dozens of his new fans and found not a single one openly obsessed with any right-populist crap. (This is not to say none existed. But for Kirchick to conflate Newsletter Paul with Candidate Paul in message and appeal is historical and journalistic malpractice, and I think is designed to traduce what was actually good about Paul in Kirchick's obsession, "muscular" foreign policy.)

From the 2008 campaign, summing up a Paul campaign speech at the University of Iowa (in which immigrants were not mentioned at all):

Get rid of the income tax and replace it with nothing; find the money to support those dependent on Social Security and Medicare by shutting down the worldwide empire, while giving the young a path out of the programs; don't pass a draft; have a foreign policy of friendship and trade, not wars and subsidies. He attacks the drug war, condemning the idea of arresting people who have never harmed anyone else's person or property. He stresses the disproportionate and unfair treatment minorities get from drug law enforcement. One of his biggest applause lines, to my astonishment, involves getting rid of the Federal Reserve. Kids have gathered, not just from Iowa but from Wisconsin and Nebraska, in classic hop-in-the-van college road trips, to hear a 72-year-old gynecologist talk about monetary policy.

He wraps up the speech with three things he doesn't want to do that sum up the Ron Paul message. First: "I don't want to run your life. We all have different values. I wouldn't know how to do it, I don't have the authority under the Constitution, and I don't have the moral right." Second: "I don't want to run the economy. People run the economy in a free society." And third: "I don't want to run the world….We don't need to be imposing ourselves around the world."

And from 2012 at UCLA:

there was a fresh strain last night among [Paul's] usual exhortations about the dangers of our profligate monetary policy and foreign policy, the unified glories of individual liberty, and the criminal idiocy of trying to police people's personal behaviors that don't directly harm others and government invasions of our privacy: he hit some high-toned notes about the larger meaning of liberty as he sees it, fitting in with a larger vision of proper human flourishing.

Paul stressed more than once—he hits a lot of his points more than once in his talks—that liberty gives us the greatest space to become the "creative, productive people we are meant to be." He is getting closer and closer to delivering a full-service libertarian philosophical vision in his speeches, though he leaves the teasing out of the coherent shape of it all mostly as an exercise for the attentive listener. He remains the total libertarian, though, taking the trouble to mention after a couple of those references to the properly creative and productive best-practices of human life that of course if you choose not to be a flourishing creative and productive being, that's cool too as long as you aren't hurting anyone else.

Paul continues to deliver his libertarian vision in language and with examples that seems 90 percent designed and ready to appeal to a progressive leftist as well, condemning crony capitalism and wealth disparities that arise from special connections and favors and stressing the wealth-creating possibilities for the masses of a truly freed market, along with his usual condemnations of war and government management of personal choices.

Things that get a panoply of booing at a Paul rally: Ben Bernanke, the 16th Amendment, UN and NATO, nuclear-powered drones, the Patriot Act, the NDAA, emergency powers for the president, government attempts to manage our food intake, and the idea that "we are all Keynesians now."

Kirchick starts and ends with the fact I suppose he thinks will unnerve readers the most: that both Paul and Trump have been frequent guests on the radio program of conspiracy promoter Alex Jones, and that Jones claims to regularly feed Trump scripts he essentially repeats.

Since I presume one of the very underlying premises of Kirchick's take is that Alex Jones is a delusional or opportunistic liar, I'm not sure why he concludes his story with the dire pronouncement that "the very archetype of the tinfoil-hat-wearing crackpot, whose claim to fame is standing on a street corner shouting obscenities, can have the ear of the most powerful person in the world" just because Jones says he does. (It would be an interesting deep-dive for a writer not Kirchick to explore the nuances of how those who have long believed the U.S. government is the endless source of baroque and sinisterly monstrous conspiracies balance that with the notion that a guy they dig for other reasons runs it. Born of such paradoxes are the sudden popularity of the phrase "deep state" and wild conspiracy theories claiming that Trump is secretly putting the kibosh on all and sundry past government evils.)

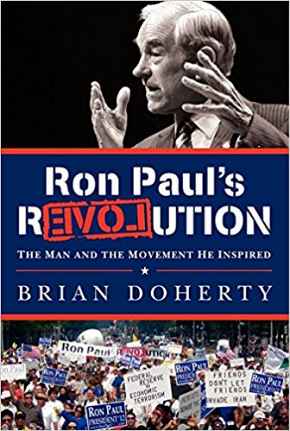

Jones makes an interesting entry point to why accusations like Kirchick's in this article rub many libertarians the wrong way. When reporting my 2012 book Ron Paul's Revolution, I asked Paul about appearing on Jones' show, which struck and still strikes many people who admired a lot about his campaign as unwise. "Because he says some things that are wrong, that I don't agree with?" Paul countered. "Well, that might exclude me from every national TV program, I mean, I get on these shows and they are pushing me on why they love assassinating American people, bombing foreign countries, and war." Whatever else those who interview him believe, he told me, doesn't "bother me one bit. I speak for myself, not for the people talking to me."

To Paul, and to many of his fans, the ideas James Kirchick has spent his career advocating—the U.S. using its wealth and lives to wage war (in Iraq), war (in Syria), and more war (in Iran)—are far more dangerous than even unhinged unsupported conspiracy-mongering. Kirchick obviously disagrees, and bases his accusations against Paul's fault for Trump on such grounds.

Kirchick's attempts to smear Paulism as the cause of the worst parts of Trumpism is likely rooted in the reason why libertarians emotionally or sociologically find it a little hard to accept his message of blame: Kirchick's most important policy concern has always been the imposition of American will around the world through war and violence, and Ron Paul was the first voice that gained any traction in the modern GOP against that sort of thing. In general, libertarians, for reasons that make sense to them, think Kirchick's world of sober foreign policy centrism is guilty of sins more significant than dumb, pandering, hateful comments made decades ago.

Alex Jones, most can agree, is crazy. Those who advocated and still advocate for the mass murder and civilization destroying powers of war are respected solons worthy of high-level publication. That's exactly the political problem that Ron Paul most tried to address, and why he most remains the target of attack and blame.

Show Comments (134)