Selling Freedom

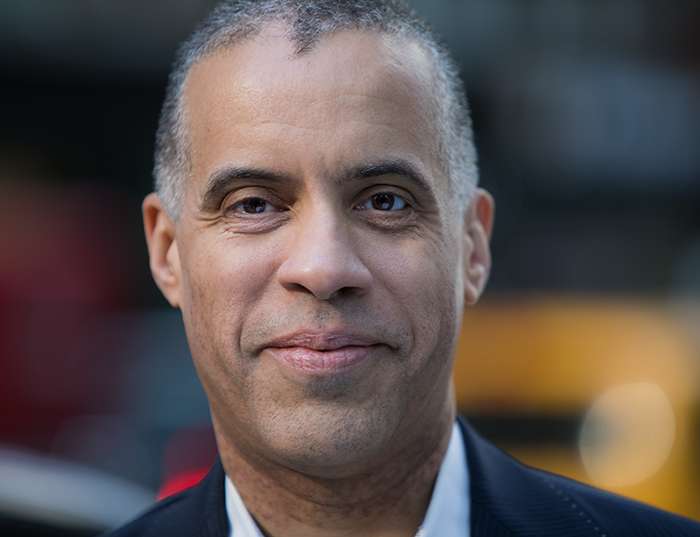

Meet Larry Sharpe, the Marine turned management consultant who is rising to the top of a leaderless Libertarian Party

Libertarians like Larry Sharpe.

It was nearly impossible to attend a state-level Libertarian Party (L.P.) convention in 2017 and not see the affable former Marine and 2018 candidate for governor of New York laying out his seven-year plan to transform the party from a distant third-place finisher to the country's decisive swing bloc at all levels of government. When I asked former Massachusetts Gov. William Weld how Libertarians could best build on their momentum, he began his reply with: "You want to get out more candidates like Larry Sharpe."

Of course, Bill Weld is the only reason a normal consumer of politics might have heard of Sharpe in the first place. Weld was the Libertarian vice presidential nominee in the 2016 race—by far the most famous and electorally successful candidate for that office since the party's founding in 1971. And in May 2016, at the Libertarian Party's national convention, Sharpe came this close to beating him. A measly 32 votes on a hotly contested second ballot separated Weld's 50.5 percent from Sharpe's 46.9, much to the bafflement of the assembled national press corps. At a raucous moment, the party's radicals and anarchists rallied behind Sharpe, even though he is decidedly not one of them.

So who is Larry Sharpe? Basically, everything your stereotypical L.P. member is not. A relentless communicator in a party represented in the last two elections by a man known for his rhetorical stumbles. A black face in a mostly white sea. An adoptee and poor kid from the Bronx whose father died when he was 11 and whose German-born mother became a convicted drug felon, in a political movement often unfairly maligned as a privileged few defending their spoils. A veteran in a party whose vice chair recently argued that joining the military to pay for college is like saying, "I agreed to kill innocent people because I wanted the money."

Above all, Sharpe is a fast-talking management consultant and sales trainer fond of saying things like, "culture change is the answer in any organization, period." Sharpe's "common-sense and empathetic communication style" is "opening up hearts and minds to a new kind of politics," national Libertarian Party chair Nicholas Sarwark enthuses. "His campaign is raising the bar for…candidates across the country."

In a decentralized party of disheveled dreamers, Sharpe's strategic patter can feel like a bracing shot of adrenaline. It also comes at a time when there are no other obvious new Libertarian frontmen, despite the party's record-shattering vote totals in 2016. Two-time presidential nominee Gary Johnson has declared that he's never running for office again. Nomination runner-up Austin Petersen has become a Republican. And Weld is even more controversial among L.P. members now than he was in May 2016.

In the matter of two short years, Sharpe has become the most effective fundraiser in the Libertarian Party. His particular specialty is raising money from the very people who complain they don't have enough of it. He'll grab anything—a "Johnson/Weld 2016" T-shirt, or some discarded campaign poster—and give it the cattle-auctioneer treatment. I've witnessed him take a book I co-wrote and, by virtue of me being in the room with 25 L.P. activists, squeeze out $200 for the damned thing. "I'm out there now because no one else is doing it," he explains.

"The Libertarian Party's been through three iterations," Sharpe tells me in late November in midtown Manhattan, not far from his office. "I'm the vanguard of 3.0, right? The end of 2.0 was Gary Johnson.…This is more of a universal phase. We're now open to the world."

If Sharpe pulls 10 percent of the vote in his gubernatorial run against incumbent Democrat Andrew Cuomo in an overwhelmingly blue state, that will be an early indicator of the position of the Libertarian Party in the next election cycle. If he ends up closer to the 0.4 percent his predecessor garnered in the 2014 race, the L.P. brass should be worried indeed.

'You Don't Have to Have a Rule for Everything'

Reason: How did you first get exposed or introduced to libertarianism, and did it take right away? What was that process like?

Larry Sharpe: I was raised in a complete Democratic New York City household. Politics, for my family, was very easy. If you had a D by your name, you're awesome; if you had an R, you're evil. Period, done deal.

But I was more interested in other things. So when I became 17, I joined the Marine Corps. My examples of leadership and manhood were mostly Republicans, and my first commander in chief was Ronald Reagan, so I think I became more of a Republican as an 18-, 19-, 20-year-old. The first time I voted, I voted for George H.W. Bush. But I was never part of a party.

Then, in '92, I heard Bill Clinton speak. I thought, "Wow, this guy's different. He's young, he's new," and I thought, maybe I'm a Democrat. Then I [realized] Clinton's the same as all the rest of them. So I kind of thought Perot was the guy. I didn't even know Perot's ideas, I just knew he wasn't them. Then I went from a Perot guy to a Nader guy.

Wow, you really checked all the boxes!

Well, if you would have asked me any of Nader's policies, I couldn't have answered; I wouldn't have known any of them. I knew he wasn't an R or a D, and that was good enough for me. I knew Perot wasn't an R or a D; that was good enough for me. I actually considered in 2000 joining the Green Party because it wasn't the R or the D, but if you'd have asked me what they stood for, I wouldn't have known. No idea. I saw that in a lot of the Bernie supporters last year—just like me, just wanted someone not in the mainstream, couldn't tell you what Bernie's policies were. A lot of the young Trump supporters, same thing. Just wanted an outsider.

In 2008, I heard Obama speak, and I thought, "All right, this guy's so different, he's got to be the real deal. I can get a winner and a change guy. Oh my God, Obama, what a homerun." But he's Bush Jr. No difference. He's the same as all the rest. My people are still going to jail, my friends are still being deported. You know what? I was pretty much done.

Then I heard Gary Johnson speak in 2012. And I thought, "Whoa, all right! Maybe this!" This sounded like me, because he's an entrepreneur like I am. He thought the same way I thought. He was the veto guy—he was the guy who said, "No, this [law] isn't going to help." That's what I had been teaching in my leadership and sales for eight years by then. Look, you don't have to have a rule for everything. Rules aren't the answer. Culture change is the answer in any organization, period. In your family, in the country. That's what matters.

But I'd been burned so many times. I did not become a Libertarian right away. I thought this guy might just be another Obama, he might be another Perot, he might be another Clinton, might be another Bush. So I actually went to the Libertarian Party, and I met Libertarians. And I thought, "Oh, most of these people are just like me." Then I went to Gary Johnson events and I met Gary Johnson. I will always be loyal to Gary Johnson. Without him I'm not a Libertarian.

What I noticed clearly in the party was what I was teaching as part of my executive coaching, my training in colleges, my training in schools and organizations—it was the idea that good leaders want to get buy-in from the people around them. Which means volunteerism, right?

The libertarian mindset works in business. We are in a post-industrial economy and post-industrial culture. Leadership has to be post-industrial, which is not about arms and legs—I can buy arms and legs anywhere. In fact, [artificial intelligence] can do most of the jobs that arms and legs do anyway. What do people need to do well? Lead well. That is, communicate, communicate, communicate.

It's getting buy-in. Things change so fast now, I don't need you to do what I tell you to do, I need you to know what the goal is, and adapt when you're there. People wonder why I can so easily espouse and talk about the principles of libertarianism. I've been teaching it for 13 years!

"I started reading Bastiat's The Law, and I loved that. He's still my favorite. I couldn't read Adam Smith's actual books; they just weren't for me. So I read the CliffNotes instead. Then I went to Hayek."

So did you at some point start going back to the classics and cracking open your Milton Friedmans, your—

I had never read any of those. The only people I ever read who were close to libertarianism were Ayn Rand and Robert Ringer. A lot of people don't know Robert Ringer—

I don't.

Robert Ringer wrote Looking Out for #1 and To Be or Not to Be Intimidated? He's a big Ayn Rand fan, and he talks about sales, and business, and branding, and leadership, which was my world. I read Ayn Rand because he was an Ayn Rander.

When I became a libertarian, I moved away from Objectivism. I still liked the Ayn Rand ideas, I like the libertarian ideals that come from it, but I'm not an Objectivist. So then I started reading Bastiat's The Law, and I loved that. He's still my favorite. I couldn't read Adam Smith's actual books; they just weren't for me. So I read the CliffsNotes instead. Then I went to Hayek, Road to Serfdom. I began to read each and every book and move on from there.

'I Don't Care About Ballot Access'

Reason: I imagine your business life kicks in when you look at the Libertarian Party's current organization. Your work is not exactly a takeover-artist situation. It's like, "Hey, these assets are underperforming, and if we just visualize and act in a different way, we can go from four to 10 pretty quickly."

Sharpe: Yes. I tell people all the time, I love going into organizations that are totally broken and on fire. I love that. Why? So easy to fix. Hey boss, this week nobody died! Oh my God, Larry, you're a genius!

From that analytical perspective, looking at the party, what has jumped out at you, besides the fact that no one comes to a follow-up meeting after the election is over?

I'm a long-term thinker, right? Again, I'm a business guy. I don't think next quarter, I think how to build my business the next three, five years. I want sustainability. I want long-term growth. The party has not had a vision for growth at all. It's been a purist party, or a let's-get-ballot-access party. People get mad at me, but I don't care about ballot access.

Really?

Don't care at all. It is useless.

Really?!

You know why? It's a means, not an end. I don't ever want to focus on the means.

Easy to say now that the means are there!

They're not there in New York! I don't have ballot access.

Victory's the panacea. That's the cure-all: Win. Everything else is secondary. Win, and you get ballot access. That's how it works. You want to get into debates? Win.

The debates aren't about the lawsuits. I support Gary Johnson, went raising money for him because I love him, and if he wants me to go down and raise money for the lawsuit I will do it every single day of the week, because he asked me to do so. Here's what I know: If we become popular, we're in the debates, period. If we had won the lawsuit last year, if we had won and they had to put us in, Donald Trump would have said, "If Gary Johnson's there, I'm not showing up." He actually did say that. If he's not showing up, there's no debate.

We get into debates if people want to see us. If we have someone who's popular, who people want to see. We get a good celebrity in 2020, we're in the debates. We get someone like, I don't know, people talk about Mark Cuban, I don't know if he's a libertarian. But whatever, someone like him, or Vince Vaughn, Kurt Russell, The Rock.

Penn Jillette.

Penn Jillette. Any of those guys, we're in the debates, period. Regardless of lawsuit, regardless of whatever. Regardless of polling. Doesn't matter. You don't put Penn Jillette in every poll. He's still popular. He's on.

'I Don't Want an Amash or Massie Right Now'

Reason: Walk us through your seven-year plan, just in terms of milestones. What do you think is achievable?

Sharpe: We are already winning city councils. We have a couple hundred already in the nation itself. It's not a lot—there are over half a million total seats that we could have. We only have several hundred of them, but we only had a hundred a couple years ago, so we're doubling and tripling. It's working. Why is that valuable? Because people will realize that if Libertarians run a city, it doesn't go under. It's not the zombie apocalypse, or The Walking Dead.

As that begins to happen, now we can move to the next level, which is the state level. We can become actual executives.

Now, in my perfect world, we have a nice celebrity on top of the ticket in 2020. That top-of-the-ticket 2020 celeb spends a lot of time talking about the people running locally. It's not just "me, super-celeb guy," it's also these people and these people. When there's a big event in Iowa or wherever he goes, everyone else on the ticket also speaks and gets up there, and we'll see them. We didn't do that well in 2016 at all. We do it well in 2020.

That will get us, hopefully, some state seats. You have to remember: In many states, if we just have three state senators, we'll run the Senate. We'll actually be a real swing bloc.

Here's the best part: When the liberty-minded people on the left and the right see that as an actual power bloc, they'll come to us. But they'll come to us three, four, five years from now when we've built up their trust. I don't want them to rush to us now, or they'll take over our party. We'll become Republican lite or Democrat lite. But if we build up an infrastructure, we won't. That's three or four years.

You don't want Jeff Flake coming to the party right now?

No, not at all.

Interesting.

I don't want [a Michigan Rep. Justin] Amash or [Kentucky Rep. Thomas] Massie either right now. I want them, but not now. They come now, we will rally around them, do whatever they say, however they say it. I don't want that.

Look, the reality of it is, a lot of more radical and more anarchist people in the party are afraid they're going to be thrown out. That's why many of them become audacious and angry. I get it. They're right; it's a valid fear. Guys like Massie or Amash come over, that might happen. We'll become Republican lite, and those guys will be like, "You aren't us." Boom, they'll be gone. It could happen. I don't want it to happen.

To be clear, if that happens, you think that's bad for the party?

Yes.

2020, it's an Amash-Massie ticket?

Bad idea.

Bad idea?

Bad idea. Bad idea.

The problem is, look, right now the Republicans and Democrats are basically just tribes. They've been tribes about 30 years. I mean that, they're just tribes. They don't have an ideology. It's rule of the king. You can't tell me a Trump Republican is the same as a Bush Republican is the same as a Reagan Republican. They're different Republicans, because the king is different. As the king changes, the party changes. There's no ideology. They're only concerned about winning and beating the other guy. Nothing else matters.

"People will realize that if Libertarians run a city, it doesn't go under. It's not the zombie apocalypse, or The Walking Dead."

We in the Libertarian Party, we fight all the time. Why? We have an ideology. If we bring them over now, and the radicals and the anarchists leave our party, we will become a tribe. I don't want to be a tribe. As much as radicals and anarchists sometimes drive me crazy—and they do, when they attack me with vitriol because I'm not libertarian enough—I need them. Even though they think I'm the enemy, I'm the only guy saying, "Don't leave."

I know when I bring people into the party, they're not going to be real Libertarians. They're going to be, this kind of sounds cool. I need these guys to turn them into real Libertarians. I wish they would stop fighting me, and start teaching the people I bring in. Show them. They haven't read Bastiat. They have no idea what an anarcho-capitalist is. They don't know what cryptocurrency is. Show them. I've opened their minds. Take advantage of it. Put some good stuff in those brains. Do it. Make them all anarchists. That'd be awesome. I'd love it.

'When You're a Radical, People Become Afraid'

Reason: So what's your pitch to our anarcho-capitalist friends?

Sharpe: In my perfect world, in my heart, I'm an anarchist. But in reality, right now, I'm a minarchist. I want to go as close as I can to that. But I am absolutely not a radical. Why? I know that when you're radical, people become afraid. When they become afraid, they make bad decisions. That's human nature. When it comes to politics, they beg for a strongman.

Government almost never just takes your rights away. Almost always we legally vote them away, because we're scared. So if I become radical, people get scared; they beg for Donald Trump. The reason we have Donald Trump now is because people are scared. "The world's ending, what are we doing, we have debt, we don't know what we're doing. Strongman, help me." Right?

Strongman's either a dictator or a socialist. That's how it works, and that's been repeated how many times for a thousand years. That's why I'm not a radical. But in my heart I am an anarchist. I would love to have a society that is based only on volunteer associations. That would be amazing. I don't think I'll see that in my lifetime. So the closest I can get to that, that's what I want.

You said earlier that you think at least the near-term future of the party is people coming from the left. Why is that?

No, no, no, no. No, no. That's not what I meant. Near-term is right. Long-term is left.

How does that break down?

The Republican Party is breaking in half. It's obvious they're breaking in half. There's the Trump side, which is just "We're mad at the world!" And there's the actual people who think the Republican Party should be about small government. Those people are coming to us fastest now. But once that break is clear, people are going to have to pick sides. In the next three to four years, give or take, in that area, they're going to pick sides. They're going to come to us.

The left is slower to come to us. But here's the difference: If I can get 10 Republicans to come to us, five will go back. Or go alt-right. When Democrats come, less of them come, but they stay. They don't go anywhere.

In the short run, Republicans will break, we'll get a bunch. In the long run, we'll absorb the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party will go away in 30 years. It won't exist. It'll be the Libertarian Party.

The most radical leftists will actually go to the Republican Party, because they're all actually autocrats. It's just my autocrat vs. your autocrat. They'll go there and they'll change the name of the party.

'The Biggest Nazi? Come On In, I'm Happy to Talk to You'

Reason: This year there has been a lot of discussion about whether there's a pipeline between libertarians and the alt-right.

Sharpe: Yup.

Libertarian Party Chair Nicholas Sarwark has been drawing some bright lines.

It's a really bad idea. It's a really bad idea. Why would I tell anyone to leave my party? How can I turn you if I can't talk to you? Come, even white nationalists, come. If I can turn you, I'll turn you. My hero is that guy Daryl Davis. You know that guy? He's one of my brothers who was out there trying to get KKK members to turn. And he keeps their hoods as a trophy. He's turned like 44 of them in 30 years. That's my hero.

The vast majority of those guys are not Nazis. They're guys who are lost. There's a couple guys who are Nazis; there's always a couple of ringleaders. Those guys are never going to change, no matter what you do. But the big chunk of people who just think this is the right answer now? Turn them. That may take a month. That may take a year. It might take a hundred years. I don't care.

You want to stop racism? Let people be racist. You want to stop sexism? Let them be sexist. Let it out in the sunlight. Let people see it. Let them understand it and get it. You can turn them. I want them all to come to me, every one of them. The biggest Nazi? Come on in, I'm happy to talk to you. I will never stop that conversation, ever.

When 10 come, eight leave, two stay. I want those two. I'll take those two, because those two would have been Nazis. They're not. They're now Libertarians. Because you're free to be who you want to be in our party; just don't force it on others. You renounce the use of force.

So if someone says, "Hey, you know what? My version of libertarianism is I think people should be free to cluster, and I'm going to join a white nationalist community, and I'm going to be a member of the L.P. executive board"?

Good luck. If you win the election, I'm fine with it. Look, remember something—in a libertarian society, you can have enclaves of socialists, enclaves of communists, as long as it's voluntary when people try to leave.

Are there lessons that Libertarians, in particular, need to learn from the electoral success of Donald Trump?

Stop worrying so much about policy. The people with the clearest policies always lose. Hillary Clinton had a clear policy, and lost twice. Bernie Sanders had no policy, neither did Donald Trump. Not that we shouldn't have policies; it's just secondary. Libertarians have been been winning arguments and losing elections for 45 years.

This interview was edited for length, style, and clarity.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Selling Freedom."

Show Comments (153)