Alabama Is Sending Another Former Prosecutor to the Senate. Will This One Be Different?

Will Doug Jones be a paladin for criminal justice reform, or a squish?

Before U.S. Attorney Jeff Sessions arrived in Washington, D.C., for a career in national politics, he served a 12-year stint as the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama. President Ronald Reagan appointed him in 1981, just as Congress was about to turn federal prosecutors into demigods.

The Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 ended parole in the federal prison system and introduced the harshest mandatory minimum sentences in history, respectively. Sessions eagerly capitalized on these laws and his Senate career reads best as a two-decade quest to expand and enshrine the powers he once used to put men and women in cages.

That makes me very curious as to what kind of senator Doug Jones will be.

Like Sessions, Jones was a U.S. Attorney in Alabama (the Northern District). Like Sessions, Jones thinks his experience as a prosecutor qualifies him to make policy. You have probably heard by now that Jones prosecuted two of the four Ku Klux Klansmen who bombed Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963, an act of terror that killed four black children; and that he secured a conviction against Eric Robert Rudolph, another domestic terrorist who bombed two abortion clinics, a lesbian bar, and Centennial Olympic Park in Atlanta.

We don't hear much about his bad prosecutorial choices.

Of the 22 sentences secured by Northern District prosecutors that Pres. Obama saw fit to commute in his second term, two of those cases either began or concluded under Jones, who was U.S. Attorney for the district from 1997 to 2001. Ramiro Cervantes received 27 years in prison for a methamphetamine charge. Jimmy Dean Gibson, another meth offender, received a life sentence in 2001.

If Jones was once the kind of person who saw fit to put nonviolent drug offenders in prison for decades, or until they died, what kind of person is he now?

Here's Jones in an interview with the Montgomery Advertiser:

The candidate also says he opposes U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions' efforts to reverse sentencing reform efforts that have drawn support in both parties as prisons have become dangerously overcrowded. Sessions earlier this year told federal prosecutors to pursue the toughest sentences possible against defendants. As a federal prosecutor, Jones said, his "hands were tied" by mandatory minimums.

"I think there were times all of my colleagues worked around mandatory minimums and tried to get flexibility," he said. "That's what Jeff Sessions is trying to take away right now."

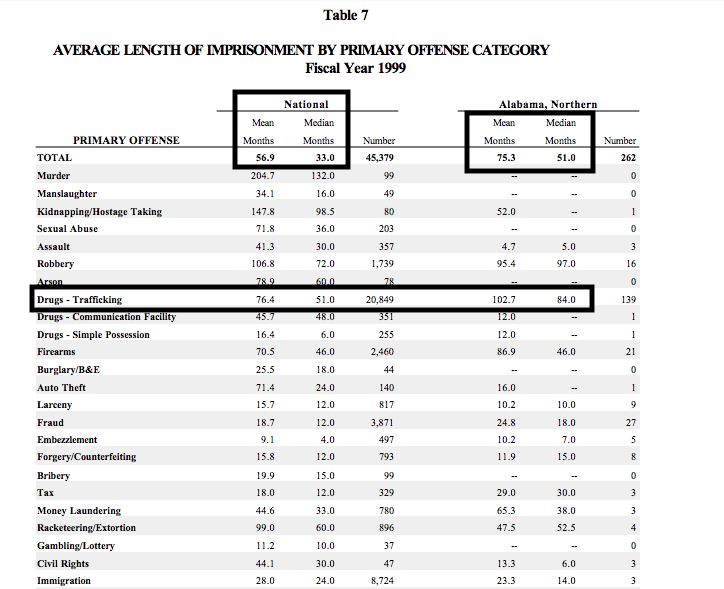

I looked at USSC's sentencing data from the Northern District during Jones's tenure to see how hard, exactly, he and his colleagues tried to "get flexibility." In fiscal year 1999, his office secured an average drug sentence that was more than two years longer than the national federal average:

The explanation for this disparity is that meth and crack, which have the two lowest quantity thresholds required to trigger a mandatory minimum, made up more than half of the drug cases Jones's office prosecuted that year (and every other year he was in charge). Prosecutors were enforcing the law as written, but I see no evidence they were trying to "get flexibility."

I don't propose to hang the failings of federal sentencing law on Jones, or any other U.S. attorney. But so long as we're assessing the good he did, we should think about the decisions he made that might inform his advocacy for people caught up in our berserk correctional system.

Sessions cited his experience as a reason to inflict more harm and steal more lives. What about Jones? What would he do differently if he could do it all over again? How proactive will he be in calling out the policies advanced by the former occupant of his Senate seat? What will he stand up for? Who will he stand up for?

Sens. Mike Lee (R-Utah), Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), Corey Booker (D-NJ) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.) could use some help advancing federal sentencing reforms, especially Leahy, who is creeping up on 80. The Bureau of Prisons should be pushed to explain why the halfway house system is such a mess and why the compassionate release program is covered in cobwebs. Someone needs to get the USSC's back as it considers amendments to the federal guidelines (the Justice Department under Sessions is already asking for the world on a silver platter).

On paper, Jones is more qualified to do these things than all but a handful of his Democratic colleagues. He's from the deep south, he served as a U.S. attorney, and he can illustrate, with two very compelling examples, where the heavy hand of the law is warranted.

But if he wants to distinguish himself from Sessions, he should consider adopting his predecessor's tenacious and unwavering commitment to shaping criminal justice policy. Sessions spent two decades successfully making the United States a more punitive place; Jones is obligated by virtue of his experience and his seat to do what he can to make it a little bit less awful.

Show Comments (9)