Dear Prudence Meets Due Process

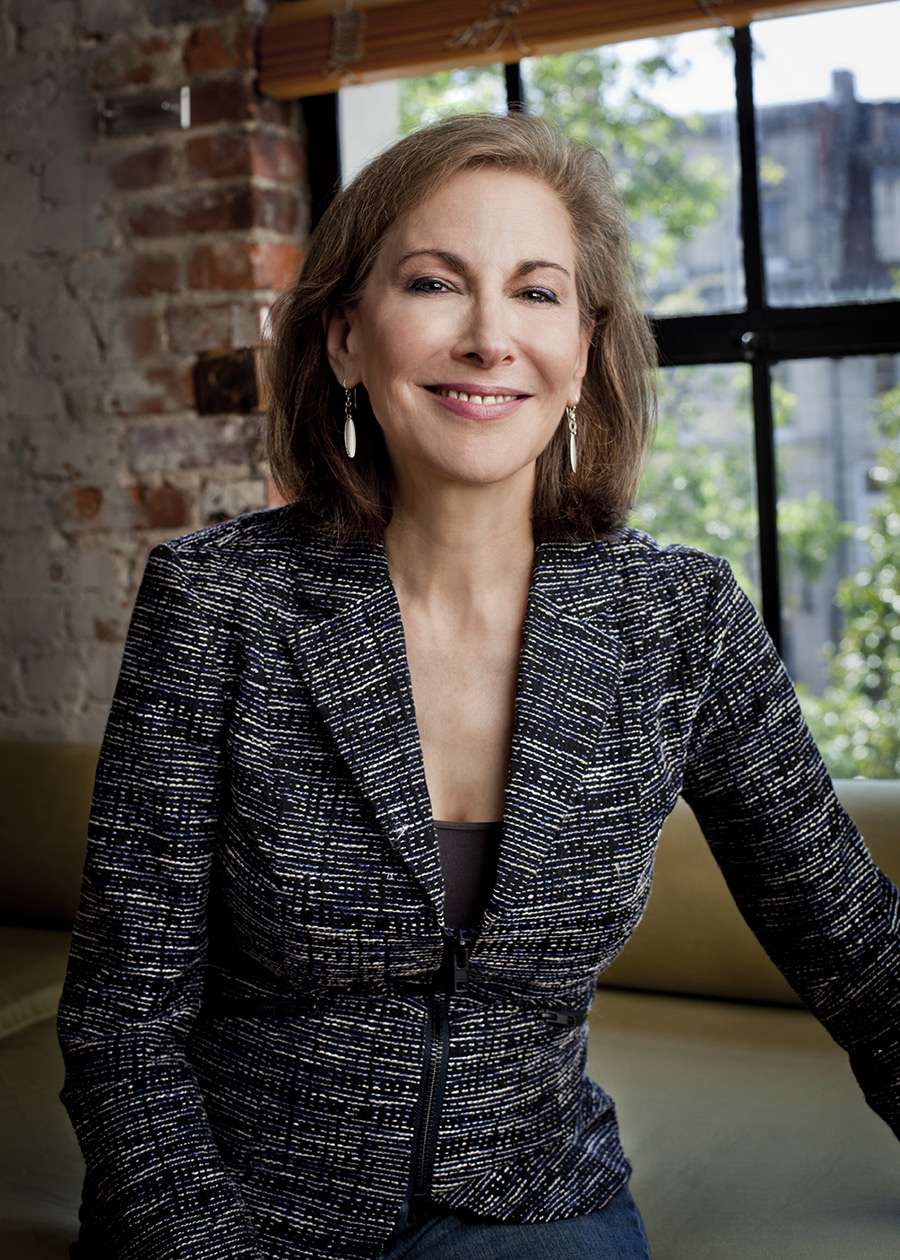

Former Slate advice columnist and Atlantic essayist Emily Yoffe takes on the campus rape crisis.

"There is no doubt that until recently, many women's claims of sexual assault were reflexively and widely disregarded," journalist Emily Yoffe wrote in a three-part series published in September at The Atlantic. "But many of the remedies that have been pushed on campus in recent years are unjust to men, infantilize women, and ultimately undermine the legitimacy of the fight against sexual violence."

These problems, Yoffe explains, are rooted in a set of directives from the Obama-era Department of Education, which nudged college administrators to adopt new procedures for adjudicating sexual assault disputes under Title IX, the federal law that prohibits sex discrimination in higher education. While the goal of such changes may have been to protect victims and bring perpetrators to justice, the rules have in practice made it vastly more difficult for the mistakenly or maliciously accused to clear their names, obtain legal assistance, confront their accusers, or even make sense of the specific charges against them. What's more, Yoffe shows, many of these efforts were predicated on junk statistics and misconceptions about how human beings cope with unpleasant experiences.

The same week Yoffe's trio of articles went live, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos announced her intention to address some of these issues—a significant victory for supporters of reform. But this arena is fraught, as Yoffe has discovered. When in 2013 she wrote a piece encouraging young women to avoid the punch bowl at parties, it received a "wave of denunciation." Daring to suggest that campus assault claims be subjected to basic scrutiny, she says, can get a person branded a "rape apologist" or worse. But "I didn't get into journalism to be intimidated about writing about difficult issues," she adds.

Yoffe, 62, recently became an Atlantic contributing editor, following a nine-year stint answering letters for Slate's popular "Dear Prudence" advice column. In September, she sat down with Associate Editor Robby Soave, who covers many of the same topics at Reason, for an animated conversation about her work and why it's worth the risk of backlash.

Reason: Betsy DeVos recently announced that she wants to chart a new direction regarding the department's guidance to colleges on dealing with sexual harassment and assault. What was your takeaway from that announcement?

Emily Yoffe: For one thing, I was surprised. I kind of thought given Trump's own problems in this area that they might stay away from this. It's very strange to have an administration led by a president I find absolutely loathsome and a disaster for this country, and to listen to a speech by his secretary of education and find myself agreeing with many of the things she had to say.

I think a danger is that it just becomes a response to the Trump administration. Schools say, "We will resist," and there's a possibility that the worst excesses will get entrenched just because of who the messenger is.

The simple narrative is, "Trump doesn't think consent is important, so he's changing these guidelines to help people like him get off the hook for sexual assault." What's missing from that story?

The problem [with rape adjudications on college campuses] hasn't penetrated the public consciousness. This three-part series of mine just ran in The Atlantic, and as we were working on the first part, which was mostly about due process—how we got here and how things have gone off the rails—I said to my editor, "Isn't this kind of old? Don't people already know this?" But he was right. People don't know that a young man can be expelled from college without ever having received specific written notice of what he's alleged to have done wrong. They don't know that virtually any encounter with a sexual element, including a joke, can get someone in deep trouble.

You cover some of the really bad science that has gone unchallenged, like the idea that of course people who are traumatized are not going to recall things correctly. Can you talk about that?

This is the so-called neurobiology of sexual assaults. I've talked to scientists who actually do study memory and response to trauma. They say they believe this is a return to the "recovered memory" scandals of the '80s and '90s [in which therapists convinced people they had been suppressing memories of childhood abuse that never actually occurred], dressed up and given a neurobiology gloss.

The federal government [under Barack Obama] started saying everyone on campus must be trained in the neurobiology of trauma. Often there would be a little footnote to a study, so I'd go look at the study, and it would have nothing to do with what they were claiming was happening to young women on campus. I think one of the strangest things about this whole field is how literally one researcher with one perhaps methodologically not-entirely-sound finding can affect millions of people.

"The problem hasn't penetrated the public consciousness.…People don't know that a young man can be expelled from college without ever having received specific written notice of what he's alleged to have done wrong."

I found that the central thing was probably a lecture by Rebecca Campbell, who's a professor of psychology at Michigan State, where she laid out the principle that people who experience a sexual assault go into something called "tonic immobility," and then afterward, they can't tell what happened in a coherent way. And if they can't remember details, if they never tried to say no, or even if afterward they texted the alleged assailant and said, "Let's have sex again," all this is evidence of the trauma. Now, that is very concerning in a legal framework, and also, Rebecca Campbell's assertions are not based on actual neuroscience.

We've seen examples of that over and over again.

And the only people who can afford a lawyer are those with means. Fighting costs a lot of money, takes a lot of time. So we don't know how many people have been [wrongly accused] who just go away.

Many people who are liberals, who believe in due process for any other group of people—for suspected terrorists, for people on death row—for some reason, when it's accused college rapists, due process goes out the window.

That is a really essential point. The new number is that only 2–10 percent of rape accusations are false. Ergo, 90-plus percent are true. So we're good to go—if she says something, she's telling the truth.

The people who are asserting this, first of all, just take it as if it's actually fact. But if 10 percent of people on death row are innocent, that's all right? Hey, that's just the price of doing business? Betsy DeVos said one person assaulted is one too many, and one person denied due process is one too many. Certainly one person falsely accused and punished is one too many. Even if you're accepting their number—let's go with the high end, that 8–10 percent are false—that should be very alarming. Advocates for reform should be saying, we have to get it right or else this whole thing is delegitimized.

It's sort of the inverse of the principle on which Enlightenment justice is built, that it's better that so many guilty people go free to protect the one innocent person.

Absolutely. But when that question is put to people in this realm, they say, "Sorry, some guys are just going to be collateral damage. Too bad." That's shocking.

The other thing I think is important is that the use of the word false is troublesome in this context, because to establish an accusation as false, we're generally saying there has been an investigation by law enforcement officials who have decided this accusation is what they call unfounded. Now, it could be the person lied. Or it could be the person said, "I believe I was sexually assaulted," but when you get the facts of the case, it doesn't meet the definition of sexual assault.

There's a study from the insurance group United Educators, which looked at all the claims of sexual assault they dealt with over several years. The average complaint was brought almost a year [after the assault allegedly happened]. So someone brings a complaint a year later, and it's this murky, often alcohol-fueled situation. I'm very reluctant to use the word false. She's not lying. She genuinely feels something happened that was wrong and is just coming to realize that now. But even if in fact what happened was a misunderstanding, we turn it into a quasi-criminal event on campus.

Often you have people who are so drunk during these kinds of events that it's hard to arrive at the truth of what happened. It can be the case that you do things when you've had a lot to drink that you wouldn't do in other situations. That doesn't necessarily mean you didn't have the right to do those things at the time. I could say you're my best friend and then not think that later.

Everyone agrees: An incapacitated person—a person who is unconscious, slurring, vomiting, falling down—cannot consent [to sex]. But an intoxicated person can, and, unlike driving, there's no clear bright-line test. At many places, these rules are really confused. I don't know if it's deliberately unclear, but what happens is the male is held responsible for his drinking and his behavior, and the female is not responsible for hers, even if under a "reasonable person" standard [she fully consented]. Here's a text from her saying, "I'll meet you in your room. Do you have a condom?" and then she later says, "Well, I was really drunk and don't remember sending that." But are you incapacitated when you're capable of writing a coherent text that addresses an act you seemingly are consenting to?

"I'm very reluctant to use the word false. She's not lying. She genuinely feels something happened that was wrong and is just coming to realize that now. But even if in fact what happened was a misunderstanding, we turn it into a quasi-criminal event on campus."

So there's a level of alcohol consumption where you would not be OK to drive a car but you would still be able to consent to sex.

And legally consent to it! In the Occidental College case, eventually it was reported to the police. They investigated, and a female police officer and a female assistant [district attorney] both said, you know, this is an unfortunate incident with two drunk kids making a bad decision, but it's not a crime.

There's an after-the-fact presumption that the male is always the initiator.

It's very sexist and patriarchal. There's a larger cultural thing out there that females don't have sexual agency or desire, or they're only acted upon, and reluctantly. And that's ridiculous.

The third part of your series focuses on the fact that we don't know what the exact numbers are, but it certainly seems like there's a disproportionate number of students of color and immigrant men who are being accused of these issues.

No one's talking about race, but in the cases where the name comes out, you type in the name and it's a black guy, it's a black guy, it's a black guy. The way you get hard numbers is the Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights demands that institutions of higher education report the race of students being punished, the way they do in the K–12 realm. But they don't. I think they don't want to know.

Let me put one little caveat on that. There's a danger. When you say we're going to collect information that could change behavior, it's not a neutral thing. So are schools going to say, "We've got to make sure we're accusing more white guys, because we could get in trouble otherwise"? That's not the outcome you're looking for.

But I talk about Colgate University, which was one of the few places you could actually get numbers because there was a race discrimination complaint brought. Colgate has about 4 percent black student enrollment, which means 2 percent black male. That year, 50 percent of the accused were black. And I had another example where the numbers were almost precisely the same at a large state school—about 2 percent black male enrollment, and the semester I was looking at, at least 50 percent of the accused were black.

In any other context, you would have people on the left saying this is a fundamental civil rights problem. We have this long history of good liberal jurisprudence fighting against the trope that aggressive black men are raping women because they can't help themselves.

That is one of the ugliest parts of American history. The majority of lynchings—Emmett Till—were because of accusations that a black man did something, whistled, walked, touched a white woman.

And obviously the situation on campus is not remotely the same as being lynched, but the people who are put through these accusations unjustly are losing thousands, sometimes hundreds of thousands, of dollars. Their job prospects drop substantially.

In the state school case I'm talking about, kind of miraculously, a very good lawyer came in at an extremely reduced rate and represented the kids who had initially been found responsible [for sexual misconduct] and got that reversed. I talked to the mother of one of the young men, and it was such a wrenching interview. She said, "I really feel I failed my son. He grew up in a mostly white community, his high school girlfriend was white, his best friends were white, and I just felt he was operating in this world, and I didn't teach him about racism." After his adjudication she said, "This was the most racist experience I've ever had in my life." Everyone adjudicating was white. She said, "I was shaken to my core."

Just think of the message: Be really careful because white women are dangerous to you. This was a sexual encounter that was later regretted. The young woman didn't even show up at the hearing. She didn't want it to go forward. It all worked out, but at great cost. I have not talked to a single young man who's been through this who wasn't suicidal, and you hear people say, "Well, if he's a rapist, he should be suicidal." OK, but we don't know he's a rapist. And if he's not a rapist, we're OK with a system that is brutal and unfair?

When I talk to accused college students, I hear their frustration that they have no mechanism to clear their name, no way to tell their side of the story.

I hear, "Well, if it gets straightened out, it's all fine." It's not all fine. Often these young men, even after they're cleared, have lost a semester. I spoke to one, a black young man at a very elite school. He was going to be the school's nominee to some of the most prestigious national awards, he was doing two theses, he was double majoring. He was cleared, but he was suicidal, he went on very heavy medication, his grades plummeted, he did no honors thesis, he bombed his graduate school exams. That's a heavy price to pay for a false accusation.

What was the process like for getting this story published in The Atlantic?

I started reporting in November 2015, and the story has been through so many revisions for fact-checking purposes. It was supposed to come out just before the election, but they pulled it at the last minute, and thank God, because of the Access Hollywood tapes [in which Donald Trump is seen bragging about grabbing women's genitals]. Suddenly, the election appeared to be turning on the question of sexual assault. In the end it didn't, but I totally agreed with pulling the article because I had this vision of myself being portrayed as defending Donald Trump's behavior, which I was not.

The election turned out not the way I or the editors expected, and so what were we going to do with this story that was written during the Obama administration? In the end we rushed to get it online, and in a bizarre way the timing was absolutely perfect, since this was the moment where the country was kind of ready to try to understand what this Betsy DeVos speech was about.

Until a few years ago you were an advice columnist. When did you first start noticing this issue?

The first big story I did on this was a 2013 piece with the infamous headline, "College Women: Stop Getting Drunk." People thought it was an op-ed type thing, but I had actually spent months reporting, reading about the history of regulation of student behavior, reading about the science of alcohol consumption, etc. The story went up and within an hour, there was an international explosion.

At the time there were a bunch of very high-profile cases that involved charges of sexual assault against women who were either unconscious or very drunk. I started looking at binge drinking and the change with women kind of trying to match men drink for drink. In the piece, I came out very strongly against binge drinking for anyone—it is dangerous for men and women—but I said there is a particular danger that arises for young women. I'm not against drinking, but you've got to find your limit and stay within it.

A central notion of this whole movement to address sexual assault, which I completely agree with, is that everyone is entitled to their own bodily integrity. You cannot do something to someone else's body without their permission. But when you get incapacitated, you give up that integrity, because other people must take care of you.

"I have not talked to a single young man who's been through this who wasn't suicidal, and you hear people say, 'Well, if he's a rapist, he should be suicidal.' OK, but we don't know he's a rapist."

You can walk off a roof, which has happened. You can choke on your vomit, which happens all the time. So you're turning yourself over to other people, and let's hope they're all guardian angels, but they're not always going to be. They could be bad people, or they could be fellow drunk people whose inhibitions are lowered, and you end up together, and potentially he does something criminal to you.

I got a tidal wave of denunciation, followed by a counterwave of support. So that was my first foray, and a year later I did "The College Rape Overcorrection."

Why are the drinking norms on campus so scary these days? Does it have anything to do with the drinking age?

I went to Wellesley College, and on the weekend you could get a bus into [Boston]. I remember going with friends, freshman year, to the Copley Plaza bar, and ordering drinks. I'm so old—we were allowed to legally drink at 18 back then. And when you go to the Copley Plaza for a drink, you are not going to have 10 drinks. You can't afford it, and it's not going to be cool to vomit on the bartender. Alcohol was available to you, so you didn't have to drink a liquor store's worth before you set out for the evening.

I'm not saying there wasn't binge drinking back then, but I don't remember that being a thing. I understand Mothers Against Drunk Driving and the other forces that [worked to raise the drinking age to 21], but I think there's been this unintended consequence of the rise of "pregaming."

College students are also no longer drinking with authority figures. You used to hear people would have cocktail parties with their professors.

I did. We had our French professor over and we all had wine and cheese together, and we were college students.

You told me that you disbelieved the now-debunked Rolling Stone story about a rape at the University of Virginia from the beginning.

I was working on that 2014 "College Rape Overcorrection" story, and the Rolling Stone story comes out and just takes the country by absolute storm. You and I both know rape happens, and this sounds like a story of a truly horrific criminal act. So I sat down to read it, and by paragraph five I went downstairs and said to my husband, "This is complete baloney. I give it two weeks, because with the attention this story's getting, there's no way it holds."

I have no gift of prophecy. Or I only have gifts of prophecy for that particular Rolling Stone story; I wish I knew what the stock market was going to do. But a textual analysis [shows] the event was not biologically possible. A glass table breaks and a bunch of guys are raping a young woman on broken glass? Everyone would be in the hospital with serious blood loss. She would have been in a life-threatening situation, and it describes her getting up and walking downstairs and no one noticed. I mean, if you've ever broken a wine glass and tried to gingerly pick it up, you always cut yourself, and it hurts, and it bleeds a lot.

And then every quote was "Jackie said her friend said." Every assertion about what happened came from Jackie.

Unlike the vast majority of these cases, this one has been definitively disproven.

But to get back to the idea that only 2–10 percent [of rape accusations] are false, the chief of police in Charlottesville, when they investigated the case, had this press conference and was like, "There's no evidence any of it happened," but "we're not closing this case. We're not calling this a false thing. Maybe some new evidence will come out." He said, "We don't want to discourage other survivors from coming forward." So this case is not [counted] in any statistic as an unfounded case.

This topic is a hard thing to write about because it's so emotional. The crimes are horrible when they happen, and the deprivation of justice is painful to watch. How does it make you feel to be on this beat?

When I was doing the initial drinking story, everyone I knew said, "Don't write about it. It's a third rail." And I remember thinking, "I didn't get into journalism to be intimidated about writing about difficult issues."

There are a lot of concerns and interests of mine that come together in this story: abuse of power, junk science, fundamental fairness. Young women—it's mostly young women, but of course men can be victims, too—do get sexually assaulted, but we undermine the effort to properly identify and punish those wrongdoers by casting the net too wide.

I open this Atlantic series with a harrowing account of a young man named Kojo Bonsu, who was falsely accused of sexual assault. He was ultimately cleared, but again, he was in a state of physical and mental collapse. He got his life back on track, but when you capture someone like that in a system, and the system doesn't see that as an error, you've got something that is not helping victims. It's destroying innocent people.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Dear Prudence Meets Due Process."

Show Comments (71)