My Fellow Soldiers: Letters from WWI

"We have been receiving patients that have been gassed and burned in a most mysterious way," Julia Stimson, a military nurse, wrote from Rouen, France, on July 25, 1917. "Their clothing is not burned at all, but they have bad burns on their bodies."

It was the world's first encounter with chemical warfare. A century later, we're still struggling with the horrors Stimson describes.

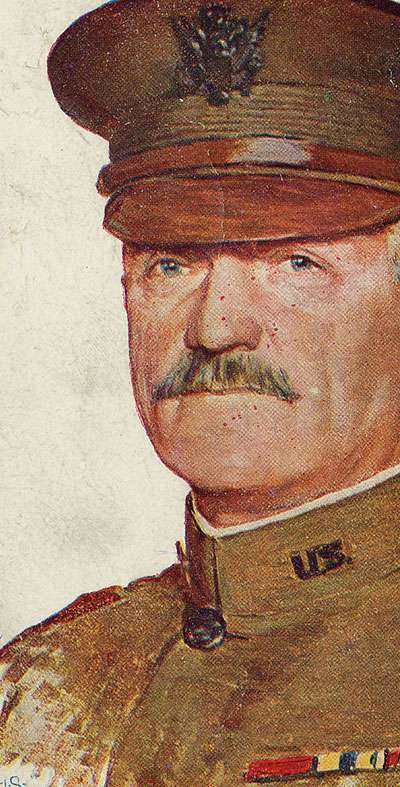

"My Fellow Soldiers: Letters from WWI," a new exhibit at the Smithsonian's Postal Museum in Washington, D.C., reveals the personal side of war, through the correspondence of soldiers participating in that conflict's final chapter, and of medics fighting a losing battle against industrial-scale warfare.

"You have never seen or imagined such pathetic figures," wrote nurse Anna Mitchell, who treated German prisoners of war, to her sister Caroline Stokes. "Everyone emaciated, in strange, ragged garments."

Other letters showcase the many mundane details of life during wartime. A wife complains that her military benefits check did not arrive. A wounded soldier tells of drinking with a "lieutenant named Hemingway." Future president Harry S. Truman makes wedding plans with his fiancée.

But even the most striking letters can't capture the trauma of the conflict. "Only numbers would give you any idea at all" of the scale of human carnage, Stimson wrote—numbers she was prohibited from sharing by military censors. The exhibit runs through November 2018, the 100th anniversary of the conflict's end.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "My Fellow Soldiers: Letters from WWI."

Show Comments (1)