How Ron Paul Gets the NFL 'Take the Knee' Controversy Wrong

Why should obsession with "cultural Marxism" mean one should fear protesting police crimes?

Ron Paul appeared on Alex Jones's InfoWars to weigh in on the controversy that has the nation pointlessly aggrieved: some football players aren't happy with how often police kill black men and choose to express this by kneeling rather than standing when the national anthem is played before football games.

Paul, the former Republican congressman (and two-time Republican, and one-time Libertarian, presidential candidate) seemed to see other things worth being angry about in the kneeling NFLers behavior and in the team owners' tolerating it, for various unconvincing and poorly expressed reasons.

President Donald Trump has chosen to cynically and idiotically fan the flames of this phony controversy, dividing the nation roughly between those who either agree that cops violently misbehave too often or that Americans should be able to peacefully and symbolically express that opinion during the national anthem at a football game, and those who think public and presidential pressure should force everyone to "show respect for the flag" in one proscribed ritual way.

Matt Welch masterfully parsed out nearly all the issues relevant to the libertarian perspective about this dumb controversy at Reason earlier this week. Among his conclusions were that it would be great to get government money and giveaways and crony treatment out of sports, and that it's a healthy thing for free Americans to react to presidential dudgeon by doing the opposite of what (he claims) he wanted. (Trump, the political imp of the perverse, likely would have been disappointed if everyone had obeyed his command to rise for the anthem.)

On his show, Alex Jones, a popularizer of the idea that the U.S. government conducts baroque and sinister conspiracies with maddening regularity and for tyrannical ends, now seems more worried that "white people" and America are being criticized. Paul, fortunately given the shadow of racist comments that appeared under his name (but were not, he insists, written by him) decades ago in newsletters he issued, doesn't directly rise to that bait, moving forward as if it wasn't even said.

But Paul apparently, for reasons he never specifies or makes clear in this interview, finds the display of kneeling by football players to be a distasteful example of a modern right-populist bogeyman, "cultural Marxism," an (often seen as conspiratorial) movement to overturn all traditional western values in order to soften our underbelly to accept totalitarian communism, through means unspecified.

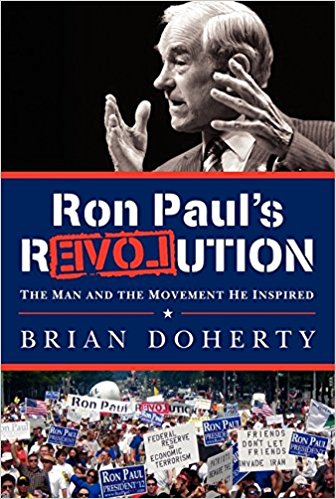

The Ron Paul who created a stir for a message of small government, sound money, and liberty in his 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns nearly entirely avoided this kind of cranky right-wing talk. I never heard him claim the free choices of any American to express an anti-government opinion in any context was something to be upset about in any way. (I witnessed dozens of hours of his political speeches while researching my 2012 book Ron Paul's Revolution: The Man and the Movement He Inspired.)

Being a politician seemed to bring out the best in him, a real rarity. When seeking a national audience as a presidential candidate, the need to appeal outside his pre-existing constituency containing many whose anti-statism had a right-populist streak gave him room to paint a wide and sympathetic vision of liberty, one with no place for griping about "cultural Marxism" or that some people are freely choosing to not embrace those old-time western family values.

That Ron Paul left right-wing culture war nonsense entirely behind, speaking instead of the human tragedies of military empire, the dangers of federal management of the money supply, the stupidity and evil of restricting our free choices that don't directly harm others, from drug use to raw milk consumption. That Ron Paul celebrated the powers of a free people and free culture to unify us and make us the best we could be, as individuals and as a nation.

His message of peace, prosperity, and a government that no longer went out of its way to help the powerful and harm the powerless seemed designed to appeal to progressive radicals as much as to staunch libertarians or the small-government right, even explaining how programs of direct help to the destitute should not be where limiting government's reach and spending should start.

In the Jones interview this week, Paul hits the correct note that President Trump should leave the NFL knee controversy alone, saying "the president ought to be a lot less noisy about it" and should not be "threatening people [like] they are committing some crime."

He also rightly said, "a lot of this got worse once football teams started talking money from government to promote supernationalism and militarism" and that "the American people should not allow government to give one cent to football and allow them to promote militarism."

Paul has built his entire political and polemical career identifying the moral crimes of the U.S. government in areas both foreign and domestic. Why should he consider it some negative "attack on tradition and culture" via "cultural Marxism" for football players to quietly refuse to show demanded obeisance to the American flag, or the American government?

He gave no hint of an explanation, and there is no decent one from a libertarian perspective I can imagine.

Paul stresses to Jones some points that are technically true, but not terribly relevant from a wide-range libertarian perspective. Pressure or restrictions on free speech not directly from government do not implicate the First Amendment, as Paul says here. True.

Yet the ability to express oneself freely is a good thing, a core part of liberty. That's why libertarians don't want government to restrict it. Those concerned with human liberty should value a culture of free expression and defend it against pressures both state and non-state, even though one does not necessarily have an absolute right to express oneself on or with someone else's property.

But to speak with Jones as Paul does in this interview of the relationship of NFL team owners and players as one of "property" rather than of contract and thus with no implications for a concern for liberty to express one's objections to government misconstrues the issue. Merely being an employee of a company does not give the company a "property right" to exercise; the employee-employer relationship is a mutual contractual one, implicit or explicit.

While the NFL could, if it wished, make employment contingent on standing for the anthem, they've chosen not to. Paul has provided no argument, and I cannot imagine one within his larger vision of the proper role of government and what makes for a prosperous and free society, as to why the players' failure to stand or the owners' failure to try to make employment as a player contingent on standing is something a libertarian should care about at all, certainly not be "disgusted" about, except possibly to cheer.

Paul encourages a "boycott" to solve this nonsensical, nonexistent "problem," which creates tensions for those who believe that free markets bind all of us across nations, classes, and creeds into a complicated but delicate system of wealth-creation and betterment for all.

Boycott is indeed anyone's right within a free market. But encouraging everyone to refuse to do business with those whom we differ ideologically or politically is a losing game for everyone, especially anyone with a radical point of view, left, right, or libertarian. Markets make us partners to mutual advantage; boycotts make us enemies. This does not mean it isn't within anyone's rights to do it. No one has a right to our business or our approval. But willfully trying to limit the wealth-generating benefits of markets to those with whom one agrees risks impoverishing us all, as those dedicated to the old-fashioned western values of cosmopolitan free trade across lines of religion, nation, and class should respect.

Thus, advocating a culture of boycott requires more heavy thought from a market advocate than Paul gives it here, especially given that he hasn't rationally established any good reason why the NFL deserves punishment.

The "cultural Marxism" he seems to be angered about was of zero concern to candidate Paul. Even current freelance popularizer Paul doesn't seem to give it very much attention, if Google is any guide.

An October 2016 episode of Paul's Liberty Report show, though, was dedicated to a rather rambling and disconnected set of comments on the matter. Paul sees an ill-defined attempt to "undermine the Judeo-Christian moral values of family" as key to imposing authoritarianism on America. He worries harsh social pressure is being aimed at, say, stores selling blue clothes to boys and pink clothes to girls; that campus officials are afraid to speak out against leftist agitation on campus; and that the notion of individual rights is being swamped by a mentality of special group rights. Paul rambles over a lot of other "cultural right-wing" concerns candidate Paul wisely left alone.

But he ends that October show with a message that the Ron Paul who was Alex Jones' guest this week should have remembered: "nobody can initiate aggression against another person"—the very message NFL's kneelers are trying to convey about American police. As Paul said in his episode on "cultural Marxism," in "a free society" one "is allowed to criticize government" and "too many people don't want that, they want people to toe the line.

"Liberty means allowing [everybody] to make personal choices, social relations, sexual choices, personal economic choices" Paul went on to say, and it should not be a "threat," it should "bring people together."

"Peace and prosperity," Paul said in that October show," is what he is "waiting for and working for." He closed with a quote from H.L. Mencken, along the lines of "the most dangerous man to any government" is the man who "without regard to prevailing superstitions and taboos" comes to the conclusion "the government he lives under is dishonest, insane and intolerable."

One might almost imagine that someone contemplating incidents of police violent abuse and murder of American citizens might come to Mencken's conclusion, and thus have a very good reason for not wanting to stand for the national anthem.

Show Comments (433)