Classical Liberalism Is Incompatible With Imperialism

Imperialism is not the highest stage of capitalism, as Karl Marx claimed.

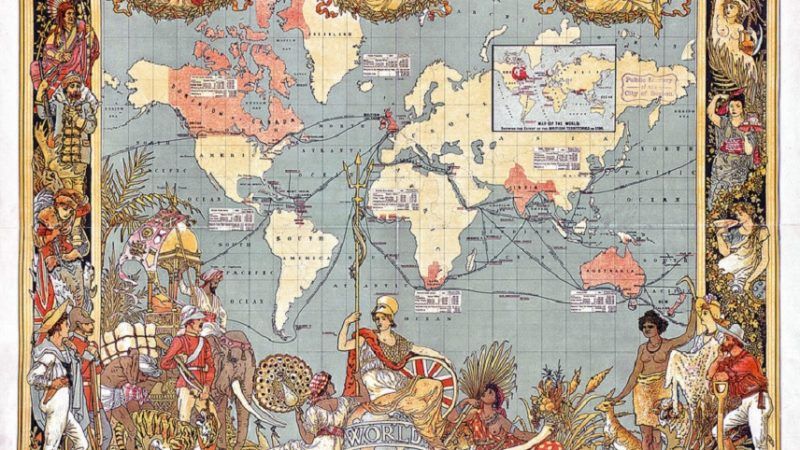

August marks 70 years since the partition of the Indian sub-continent and the beginning of the slaughter that followed the creation of Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. The anniversary occasioned much intellectual self-flagellation in the United Kingdom, even though, as Christopher Booker explains, the former colonial power did try to keep its old colony together.

In general, libertarians are not in favor of imposing Western values on people elsewhere, even though we happen to believe that political and economic freedoms are desirable and beneficial. That has long been the case. Adam Smith was an avid anti-imperialist who thought that empires were "a waste of money," while Richard Cobden thought that free trade and non-interventionism in foreign policy should go hand in hand.

"So far as our commerce is concerned," Niall Ferguson quotes from Cobden in his 2004 book Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, "it can neither be sustained nor greatly injured abroad by force or violence. The foreign customers who visit our markets are not brought hither through fear of the power and the influence of British diplomatists; they are not captured by our fleets and armies; and as little are they attracted by feelings of love for us… It is solely from the promptings of self interest that the merchants of Europe, as of the rest of the world, send their ships to our ports to be freighted with the products of our labour."

Why rehash this seemingly ancient history? Because classical liberals and libertarians are not the only critics of imperialism. Communists and their fellow travelers, while ignoring the vast imperial domain that the Soviets built for themselves in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, have picked up the baton of anti-imperialism and used it, very effectively, to bludgeon the advocates of free markets as neo-imperialists. In fact, one of the biggest and most pernicious myths in the literature of economic development is that capitalism exploits the many, such as the colonies, while benefiting only the few, such as the colonial powers.

The origins of this myth go back to Karl Marx, who thought that, under capitalism, competition would drive down profits, thus necessitating greater exploitation of the workers. The mistaken theorizing of the German economist (real average global income per person rose by factor of 10 over the last 200 hundred years) was then updated by Vladimir Lenin in his immensely influential 1916 pamphlet, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism.

The update was necessary because by Lenin's time, the workers in the western industrialized countries were unambiguously better off than when Marx wrote Das Capital (1867). And so, the first dictator of the Soviet Union invented a new thesis. Contra Marx, the living standards of the western workers continued to improve, Lenin argued, because of the riches that flowed to the West from the exploited colonies. Lenin's thesis had a profound effect on generations of Third World leaders, who rejected capitalism and embraced some form of socialism instead. To this day, most of the developing world remains less economically free than most of the West.

Colonialism and the developing world's reaction to it have led to much misery, but the West has not escaped its imperialist past unscathed. In his new book, The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity and Islam, the British writer Douglas Murray explains how colonial guilt undermines Western confidence and makes Westerners uneasy about the morality (i.e., justice) of the global distribution of wealth.

But, as Deirdre McCloskey shows in Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World, "colonial wealth accumulation" cannot, mathematically speaking, account for the 16-fold increase in the Western standards of living since the early 1800s. Similarly, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Angus Deaton and University of Maryland philosophy Professor Dan Moller, have shown that Western prosperity preceded Western imperial expansion (i.e., Western imperialism was an outcome of rising property in the West, rather than the reason for Western prosperity).

For those who doubt these modern takes on the origins of Western prosperity, consider the words of the British writer Samuel Johnson, "By what means are the Europeans thus powerful; or why, since they can so easily visit Asia and Africa for trade or conquest, cannot the Asiatics and Africans invade their coasts, plant colonies in their ports, and give laws to their natural princes? The same wind that carries them back would bring us thither."

Johnson wrote those words in 1759, 22 years before James Watt discovered the steam engine. As late as 1789, European settlements in sub-Saharan Africa still consisted of only a small Dutch colony in the Cape of Good Hope and a few Portuguese stations along the African coasts that would (much) later become Angola and Mozambique.

All in all, imperialism is a bad idea and we should have none of it. That said, imperialism does not and cannot explain either the roots or the extent of Western prosperity.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"it can neither be sustained nor greatly injured abroad by force or violence."

Commerce absolutely can be greatly injured by force or violence abroad. The Confederacy effectively wiped out Union-flagged ocean commerce around the world by 1865, with a shockingly small fleet of commerce-raiding ships. Germany almost completely cut the UK off from foreign imports with its submarine campaign in WW2. There are many more examples in history, and that is why nobody seriously argues with military operations to suppress pirates and local governments who threaten international trade.

Isolationism truly is feeding an alligator and hoping it eats you last.

It's true that western economic growth was the result of many factors beyond the simple exploitation of the non-western world, but that exploitation continued for centuries on a gigantic scale. The gold and silver that poured into Europe from Spain's American empire was mined by slaves. Millions of African slaves were imported, and worked to death, in a broad area centering around the Caribbean and reaching from Maryland to Brazil.

When Great Britain conquered Dutch South Africa, they passed a law making it a felony to teach a black African to read or write, or to teach any skilled occupation--brick-layer or carpenter, for example. All of the fertile land was confiscated, for European use only, and blacks were herded onto small "homelands", far too small to be worked agriculturally. The idea was to give blacks no way of survival except to work in the mines. When black Africans still refused to work for what the mine owners considered "fair wages", starving Chinese were imported as virtual slaves. Back in the UK, this resulted in the "Pigtail Election" that drove the Conservatives from power.

You could also consult Shikha Dalmia on British activities in India. I suspect she could give you an earful. (I could too but I'm only allowed 1500 characters.)

This cannot be true. Only white Americans were slavers.

Slavery was not an economic institution for thousands of years, practiced across the world.

It was a purely racists institution practiced only in North America for less than 100 years. (The indentured servants from Britain were not slaves, only when America became independent did they become slaves. No Africans were made slaves and then imported to America, they only became slaves the moment they touched North American soil)

What makes America and the West historically exceptional is not our imperialism, slavery, or atrocities committed against people with inferior technology. Those were pretty standard and common practice in all civilizations.

What makes us exceptional is that we now think all these things are universally bad. That is an incredibly uncommon quality in any civilization throughout history. Nearly every culture and civilization in history considered the number of people they conquered and enslaved to be something to be proud of. The Europeans were just lucky enough, mostly due to climate and local geography, to invent the ocean-crossing warships and guns first.

Every human being on Earth should be thankful they live in 2017.

That and that there is an America to show that Liberty, freedoms, and civil rights are superior and probably necessary to have the most successful economy in human history.

Amen!

We are human, will struggle and fail, but we persevere. Sadly, statues of Jefferson will be the next to be taken down because he was a slaveowner, but this misses the greater point, that he was hopeful for a better republic for all people.

Liberty and freedom are not guarantees of wealth, but of the ability to pursue wealth, or knowledge, or beauty, or happiness.

Empires get in the way of all of this.

Sorry, which of those things did you think still existed in the us?

They still exist in the USA but thanks to those who do not cherish them, Liberty, freedoms and civil rights have been curtailed.

"What makes us exceptional is that we now think all these things are universally bad."

I wouldn't quite word it like that, but yes colonial and other empires are just govts. in particular, govts that are farther away than usual. If we're going to presuppose all govts are evil then great, but let's not pretend that every empire just walked into the garden of eden and took free people from their anarcho-syndicalist communes and made them oppressed subjects. People were generally already in the latter group and just had to learn a new emperor's name.

Another modern plague unto the world is "racism". It's actually just a class system. Such as have always been throughout history. Not saying they're good at all, but they're not america's special sin or secret sauce either.

But "Europe" was uniquely evil. Imagine the peaceful societies that would have arisen if "Africa" or "North America" had developed first.

Imagine the utopia we would live in if the Mayans developed the ships and guns first and took their empire global.

Of course you would have wanted to point out in your (part 2) segment that Africans rounded up many of the Africans slaves and that many other groups assisted Europeans in rounding up slaves and workers to be exploited.

The point being that slavery and exploitation are bad but it was not just Europeans who did this. Europe and Asia have grown and gotten wealthier without slavery and exploitation while Africa has not.

America started out having slaves but moved from that first in the North and then after the civil war in the South. America has since become the most successful economy in human history because of embracing freedoms to further said trade. Even China cannot compete because they are communist and you don't own your property nor what the Communist Party does not want you to have.

Also, essentially all of the wealth achieved through slavery was wiped out in the Civil War. Any acquired wealth in the South, which was already much less than in the slave-free north, was destroyed by the time the war was over. There is almost no lingering wealth from slavery.

Wealth was not wiped out by the civil war. The civil war only affected very few areas with devastation. The rest of USA, outside the South, grew.

The South's entire economic system changed, so there was definitely some poverty and slaves were already poor but had the ability to earn wages. The huge tracts of land in the South still remained and produced crops that gained wealth.

Wealth for one family. If that "huge-tract-of-land owning family had three kids per generation over eight generations in 200 years, then that wealth would need to be spread over about 6000 descendants before you see net progress. The labor that number of people can produce is far more valuable, by orders of magnitude if it is skilled labor. They have huge tracts of land in lots of shittier parts of the world too. A few people do great. Other people can barely get by there doing unskilled labor. As we know from our economics class, they are paid based on how much they can produce via the laws of supply and demand, and given what we see in agricultural sector wages in shitty places, they clearly don't produce much. Meanwhile people open factories and hired skilled labor and look what happens. Fucking economic development miracles.

Indeed. This is why the places that continued to practice slavery the longest, such as Cuba, "the confederacy", and Brazil, not to mention places like India and Uzbekistan in modern times, were and are the most powerful and richest countries in the world. Further we see that development always ceased and even regressed once slavery was outlawed in other places. Specialization and skilled labor simply can't compete with whippin' people.

"Classical Liberals"

Aren't they the ones that always rode into battle on unicorns?

Nope. Just Libertarians who strike down lefty socialist nonsense every day like the hammer of Thor. The thunder of our vengeance will echo through these corridors like the gust of a thousand winds!

Communists stand on the shoulders of capitalists, pointing fingers and calling names like "imperialist". It's quite silly.

Minor quibble: James Watt did not discover the steam engine. Newcomen (sp?) had the first practical steam engine, I believe, used to pump out tin mines in Cornwall. It was laughable except that it did actually work. James Watt improved it -- Newcomen's engine sprayed cold water on the cylinder to cool it and condense the steam, so the following steam power stroke had to reheat the cylinder before the steam could actually stay in steam form and raise the piston again.

Watt's big improvement was to add a valve which redirected the steam into a separate cold chamber so the cylinder stayed hot.

These steam engines were low pressure and inefficient -- 5-10 psi, IIRC. Watt got a royal patent for his work. A bunch of independent inventors tried making higher pressure steam engines which would be small enough for ship sand even trains, but Watt shut them all down with his patent. The sorry thing, I suppose typical of all patents, is that Watt did not know the metallurgy to make higher pressure steam engines, so ships and trains had to wait for Watt's patent to expire. It's why Robert Fulton created the first steam ship in America, where Watt's patent did not apply.

Sheesh now you're going to tell me Steve Jobs didn't invent the mp3 player.

Ha!

No, I despise intellectual property, patents and copyrights, and Watt is one of my Hall of Fame examples of how patents rewarded the wrong guy (what was Newcomen, chopped liver?) and held back progress.

Then there's the Wright Bros. Indubitably far ahead of their peers, they still had some wrong ideas which their wind tunnels didn't uncover (they thought aerodynamic lift only worked with thin wings which couldn't have any interior structure, thus you had to have biplanes), their first flight was a cheat because it needed a catapult to get off the ground, but they were still far ahead of their contemporaries. They went to Europe in 1908 (?) and literally flew rings around everybody else, I think circled over a racetrack for an hour or so when nobody else could even manage a controlled single lap.

But they sat on their patents, expected teh world to come begging, while their incompetent contemporaries kept on working and improving and left them in the dust. Then they got into a ridiculous patent fight with Glenn Curtis which was only resolved in 1917 by the US Government practically buying their patent so they could build planes for WW I.

Another fine example of patents deterring progress for no gain.

"Slavery is wrong because it denies people self-ownership! Let's abolish property rights, including self-ownership!"

Gee: I wonder why communism runs out so horrible in practice.

Any philosophy, if taken to uncompromising extremes, is incompatible with every other philosophy.

That said, in practice all philosophies compromise, including "classical liberalism" and "imperialism". And as we saw historically, while they may not synergize, they weren't incompatible. Because -and I can not stress then enough- real people compromised. You just can't run a country/empire/whatever without compromise. So that means sometimes you go all "classical liberal" on a policy or positions, sometimes you go all "imperial" on it, sometimes you go "capitalist", sometimes you go "socialist" and so-on.

Because even when you can accurately broadly describe a nation under a single label, there's always going to be parts that don't quite fit. Because nations don't run well with uncompromising extremes of political philosophy.

Imperialism isn't really a philosophy. And your sophistry is noted, but ignores the arguement that the ethical basis of classical liberalism precludes imperialism.

Not necessarily. A benevolent form of Imperialism is actually embedded into the ethos of British classical liberalism. The argument was that a consistent & united civil order would be required in order to protect the sovereignty of the individual. So long as it was not through war, but through economic and hegemonic growth, it is morally obligatory in theoretical practice. Therefore, the natural rights of an individual in India would have the same protection and respect as the natural rights of an individual in London. Without an imperial order, there would be no authority that could maintain the stability of a liberal society in any place other than the hegemon; there would be no power to prevent others from initiating force against those who are vulnerable. For example, if we completely abandoned our alliance with South Korea, there would be nothing to stop North Korea from invading.

It was essentially a utilitarian argument.

You are very correct. The author also seems to disregard the fact that the British classical liberals of the 19th century advocated for a form of benevolent imperialism as a means to establish primacy both in order to maintain a consistently liberal order and to prevent aggression. John Stuart Mill was a big proponent of this, and it was argued from a utilitarian perspective. It was also the basis of F.A. Hayek's, and later Milton Friedman's, argument in favor of globalization, as the consequences would inevitably cultivate economic and cultural growth.

In fact, one of the biggest and most pernicious myths in the literature of economic development is that capitalism exploits the many, such as the colonies, while benefiting only the few, such as the colonial powers.

One of the bigger myths is that capitalism cannot possibly exploit anyone because free markets are competitive and competition eats away exploitive profit/rent. IOW - Marx is wrong because Marx is right. Or possibly - libertarians (the modern claimants to the classical liberal mantle here in the US) are right because ducks eat strawmen for breakfast.

Maybe - just maybe - actual classical liberals should kinda look back to that classical economics era. When it was they (and yes even Marx was 'classical' in some of his early analysis) who were pointing out the real problems of monopoly and rent and cronyism and viewed that obsessive wart-pointing as the source of future liberty. BEFORE they decided to become the useful idiots for the rentier class.

Its not that you will NEVER has monopolies or exploitation. Its that free market allows for those conditions to change quickly because competitors can easily enter the market and do things better to gain more market share.

This is why even the utility market needing to be so heavily regulated is BS. It makes sense to some that you only want one set of water pipes in the ground or one set of telephone lines, so you use government to artificially keep prices down, etc.

The problem is that cell phones which do not use telephone lines to every home have almost made regular landline phones obsolete. This could have happened decades before if government had not help create the AT&T monopoly. Then there might a period of a single cell phone company monopoly. People would be free in an actual free market to create a new technology that makes cell phones obsolete.

London had multiple competing water utilities with their own sets of water pipes.

A lot of cable companies would have paid to erect their own poles and string their own lines, but municipal monopolies forbade it and cities weren't about to lose that lucrative crony compensation.

(I realize you said "to some".)

No you pointed out good examples of multiple utilities. I just bring up the landline vs cell phone example because cell phones are completely different technology rather than just more telecoms putting more landlines on poles.

Public water supplies are a harder one to imagine better technology but private wells are one alternative.

One of the best case studies or histories of what actually happened then would be a economically-intelligent biography of Hazen Pingree (warts and all - not just the usual hagiography/demonology stuff of bios) - mayor of Detroit in the 1890's. They had competing streetcars - and electric lines - and other stuff. And they created serious problems where there was no 'answer' as to what to do. But the 'cronyism' and corruption overwhelmingly originated from those companies (ie their requirement that they get exclusive easement/etc - otherwise no capital investment) - not from bureaucrats/municipalities looking for mordida.

That's also kind of the rough timeframe when classical liberals stopped being advocates for economic liberty for the have-nots and started being advocates of economic liberty for the haves. And thus lost their ethical credibility and their focus on actual cronyism/rent/etc. So afaik there is no such biography of him.

I'll have to look into that. Any good sources?

I don't think there is one of those biographies. There is source material which is how I ran across him but nothing afaik that has been researched and put together in a complete story. His wiki entry tells me he's an interesting guy for a bio but it hasn't been written.

Ah. I was hoping for more on the trollies and such. But it's probably like a lot of other interesting cases which only exist as part of some other bigger story, liek how I learned about London's multiple water companies in an article on the cholera epidemic traced back to a single water fountain; I think it was mainly about the map produced by the doctor who discovered it.

I originally was looking at the electricity companies (who were busy pulling down other company's poles and stringing their wires on other poles). But there is some stuff online (from detroittransithistory - the pingree years) on the streetcars too:

http://bit.ly/2wCuobP

But it is clearly just skimming the surface

Thanks -- looks like some interesting crony tales.

Its not that you will NEVER has monopolies or exploitation. Its that free market...

This was kind of my point. 'Capitalism' is NOT necessarily 'free market'. Conflating them as if they are the same is how classical liberals and classical economists turned into useful idiots for the rentier class - and began ignoring 'monopoly' and 'rent' and other sources of exploitation because - 'free market' will make them disappear. Which it won't if 'capitalism' is not 'free market'.

Capitalism is defined by capitalists as a market economy.

Maybe you define it differently (socialists certainly do, but why would you go by their definition?), but then we're just debating semantics.

It's not just semantics. Capitalism is about ownership - which is essentially static. Markets are about exchange/trade - which is essentially dynamic. Obviously 'capitalists' (and 'socialists' for that matter) will want to define their preferred form of ownership as leading inevitably to the structure of exchange/trade that they say they prefer. But simply asserting that does not make it so.

Hell on the most basic level re 'the role of government' - ownership requires VIGOROUS government to protect property (and both Smith and Marx saw that as the origin of govt in their economic histories). Govt is at best damn near useless in markets even if their intentions are good (often not) and their knowledge is complete (never) and they do 'change' and adapt well (ha).

And golly - that gets us right back to this article. Imperialism and colonialism are VERY compatible with both capitalism and socialism - just govt force exerted on behalf of current owners (whether private or 'society') to expand the sphere under which preferred rules of ownership will be common/enforced. It isn't compatible with classical liberalism - because classical liberalism focused on the dynamic stuff - market/exchange/trade - where the static stuff - ownership - ends up being a consequence/result.

I've always assumed that the term "classical liberalism" was coined to refer unambiguously to the same things that "liberalism" simpliciter did before that term was stolen during the 1920s/30s*.

If that is the case then Tupy's argument becomes stronger in the light of the history of "liberal nationalism", which was a movement precisely in opposition to imperialism. A classic(al) example was foreign support for Greek independence from the Ottomans.

Of course most of what is now described as "nationalism" is incompatible with classical liberalism. I blame Bismarck. Sink the bastard.

I've always assumed that the term "classical liberalism" was coined to refer unambiguously to the same things that "liberalism" simpliciter did before that term was stolen during the 1920s/30s*.

If that is the case then Tupy's argument becomes stronger in the light of the history of "liberal nationalism", which was a movement precisely in opposition to imperialism. A classic(al) example was foreign support for Greek independence from the Ottomans.

Of course most of what is now described as "nationalism" is incompatible with classical liberalism. I blame Bismarck. Sink the bastard.

Venice and Poland are examples of democratic nations that did not build empires. They spent much of the past 300 years under the control of other nations. The innovation that comes with Capitalism is difficult when you are struggling to preserve your family and culture after being conquered.

A willingness to defend territory and citizens is necessary to have a thriving economy. A strong economy provides the means for a strong military. It's a cycle or growth. Countries and cultures with a larger footprint have more allies and more security.

(1/6)

I agree that classical liberalism is fundamentally at odds with "imperialism" should the term be defined as the as the practice of aggression, conquest, and militarism (and, to a greater extent, mercantilism and European-style colonialism), sure, but "Imperialism" is a vastly complex, if not sometimes nebulous concept.

"Empire" is really just a geopolitical term, and "imperialism" refers to the practice of establishing or maintaining an empire. An empire is simply a geopolitical power consisting of multiple countries or regions that are aggregated under one general order. That's it. Sometimes they are all united under one government; sometimes it is more devolved, and these countries still retain some degree of sovereignty (aka "Hegemony"). Empires don't have to be totalitarian or authoritarian, since they aren't a system of government. The term "emperor" did not even take on a royal connotation until the Middle Ages, when the kings of Europe wished to harken back to the political traditions of Rome. The Roman emperors were not viewed as monarchs; more accurately they could be described as being along the lines of a "CEO". The latin word "Imperator", which was not even the official title the emperor held (which was "princeps", or "first leader"), has nothing to do with royalty; "Imperator" roughly translates to "commander in chief". In truth, empires can exist under any political order, including a libertarian one.

(2/6)

Historically speaking, empires have been a critical component of the geopolitical landscape. Global superpowers have been fundamentally necessary as a means of both maintaining regional stability and sustaining civilization. Without the presence of hegemony, chaos and war may be easily enabled. When the Ottoman Empire collapsed, the Middle East was plunged into chaos. The British and French briefly stepped in to fill the void that the Sick Man of Europe left behind, but once they withdrew, the entire region degenerated into the chaotic state that it is to this day. Another example of this would be the Fall of the Roman Empire. Through its primacy and benevolence (during its Imperial period, it did not embark on campaigns of conquest as the Republic had), Rome preserved both peace and cultural consistency throughout Europe, Africa, and parts of the Middle East. After it had fallen in the West, the Dark Ages were ushered in. Other than the Franks during the 9th Century, Europe knew no hegemon until really the 1400s. The only thing that held Europe together was the shared ecclesiastical culture and a certain vague loyalty that each kingdom had to the Vatican. In the meantime, the Caliphate flourished, thus cultivating an enlightened culture during the Golden Age of Islam.

(3/6)

I would argue that, for a civilization to prosper - let alone survive - it is crucial that it have a hegemon; a superpower must always lead the way for the good of not only cultural progress but also the basic sustenance of a peaceful society.

It is simply untrue that certain aspects of imperialism are incompatible with classical liberalism. As a matter of fact, a specific type of imperialism is actually a philosophical component within liberalism's very ethos. Thomas Jefferson, for one, declared that it was America's destiny to become an "Empire of Liberty" that would spread its liberal principles worldwide and become liberty's ideological harbinger. John Stuart Mill, who first came up with NAP, was an avowed imperialist. Yet, at the same time, he was a noninterventionist. On utilitarian grounds he opined that it was the moral prerogative of the British Empire to maintain its empire, its primacy, and its hegemony for liberty's sake. To him, it should exist as a vessel to bring liberty to every individual throughout the empire and allow them to live free lives, with the government's only right to force being if one subject deprives another of his right to liberty.

(4/6)

Essentially, the best way for liberty to find its way to the most people - the best way for liberty to thrive - would be through the primacy of a liberal order. Mill called this "Tolerant Imperium"; it was the sole reason for which an empire should exist. The minimal state at its center derives its legitimacy from the sovereignty of the individual, of which it puts at the forefront of its civil duties. Through its primacy, the "Tolerant Empire" conducts itself only through the utmost benevolence, and through such thus exercises its supremacy as a means to stimulate other nations, lead its allies, and peacefully spread its influence to illiberal orders. Influence cannot be spread through force, and aggression is only morally warranted should a rival order issue force against that which upholds liberty.

To Mill and most British libertarians throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries, the unenlightened corners of the world deserve to be given liberty, and the people should be allowed to know their natural rights (think Plato's Allegory of the Cave). Therefore, imperialization would be in order, theoretically speaking. However, imperialization through conquest and exploitation were not, as such actions would fundamentally negate the idea of freedom itself, as doing so would be coercive. The moral method would instead be through cultural exchange, establishing clients, and asserting economic supremacy.

(5/6)

In some regards, the British Empire became this "benevolent empire" later on. Its participation in the Scramble for Africa and some of its actions against the Indian people were at the very least problematic, but it became the first of the European powers to abolish slavery throughout the entirety of its dominion. If it hadn't been an empire, it would have lacked such a vast jurisdiction, and it would thus not have been able to do that.

The United States is the superpower of the age, and thus holds the mantle of Superpower. American hegemony is critical to the maintenance of world peace and is the best vessel used as a means of advancing liberty. Without its supremacy, China and/or Russia would spread - powers that are fundamentally illiberal. I think it is the duty of the U.S. and her allies to use the influence that they have to protect the liberty of citizens and behave diplomatically when dealing with nations that are illiberal. The way we introduce liberty to them is not through conquest, as the neoconservatives wrongly think; that just destabilizes them more and leads to further resentment towards liberty. Instead, we can continue to use globalization as a means to bring such ideals to these parts of the world. That is what it means to be an Empire of Liberty.

(6/6)

Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek - both of them classical liberals - were fond of asserting primacy for the good of globalization. To them, it was the best way of curbing authoritarian ideologies and the influence of world orders that are fundamentally opposed to the notion of liberalism.

So, essentially, in my opinion, that is, I would argue that "Imperialism" as in "the geopolitical existence of empire", and to a more philosophical extent the notion of John Stuart Mill's "Tolerant Imperialism", is NOT opposed to classical liberalism one bit, as it can be used as an effective & inherently progressive means to uphold and spread liberty. Furthermore, this notion of "Imperialism" is actually embedded into the DNA of Classical Liberalism itself!

However, Imperialism through conquest and aggressive expansionism is incompatible with a truly liberal order.