The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Appellate court requires online tabloid to remove photos accusing recently withdrawn presidential nominee of participating in figurative 'lynching'

As I wrote last month, a lawsuit in New York courts has led to an unprecedented (at least in recent years) injunction against criticism of someone who was until recently a presidential nominee to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. Earlier this week, a New York appellate court essentially narrowed the injunction, but still reaffirmed parts of it - and I think this blatantly violates the First Amendment.

First, the backstory (and see here for more): Chris Brummer (Georgetown University Law Center) was nominated in March 2016 by President Barack Obama to serve on the commission; his nomination was withdrawn in March 2017. Even before the nomination, Brummer held a prominent position as an adjudicator on the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) National Adjudicatory Council (NAC) - a government-authorized self-regulatory system that has the power to effectively ban stockbrokers and others from the industry.

Some time before his nomination, Brummer participated in an NAC decision that upheld a permanent ban on two stockbrokers, Talman Harris and William Scholander, from associating with any FINRA-regulated firm. The stockbrokers are both black, and so is Brummer. Harris has since been convicted of fraud in a different matter and Scholander has pled guilty to fraud in an aspect of that matter.

As a result, Brummer drew the ire of the Blot, which I think can be fairly described as an online tabloid that's big on insults and leaps of inference (at the very least). The Blot is run by Benjamin Wey, a rich financier who is now under indictment for securities fraud, though some important evidence against him was recently thrown out on Fourth Amendment grounds. [UPDATE 8/10/17: The government has now dropped the charges against Wey.] Wey also recently lost a high-profile sexual harassment and defamation lawsuit, Bouveng v. Wey, which also involved statements posted on the Blot.

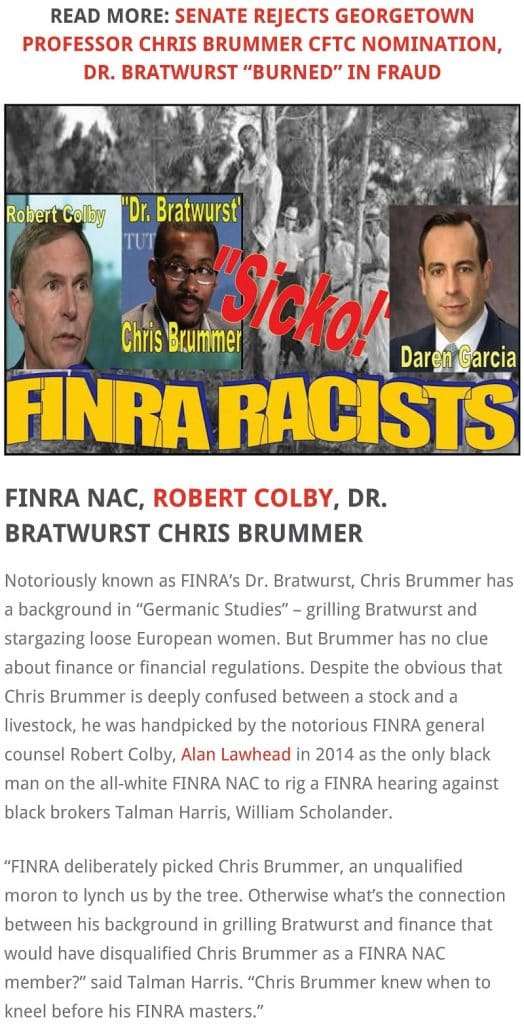

The Blot began to run articles such as this, which essentially accused Brummer of participating in a figurative "lynching" of Harris and Scholander:

Brummer sued Wey and related defendants for defamation, which of course he had every right to do - but even before trial, the trial court issued a preliminary injunction banning defendants "from posting any articles about the Plaintiff to The Blot for the duration of this action," and requiring that they "remove from TheBlot all the articles they have posted about or concerning Plaintiff." That injunction, I argued in the original post, violates the First Amendment.

Wey promptly appealed, and the injunction was stayed by an appellate judge; but last week, the New York intermediate appellate court partly lifted the stay, and thus partly reinstated the injunction. In effect, the injunction now provides that defendants must

remove all photographs or other images and statements from websites under defendants' control which depict or encourage lynching; encourage the incitement of violence; or that feature statements regarding plaintiff that, in conjunction with the threatening language and imagery with which these statements are associated, continue to incite violence against plaintiff

and that defendants are

prohibit[ed] … from posting on any traditional or online media site any photographs or other images depicting or encouraging lynching in association with plaintiff.

I think this continues to be a massive First Amendment violation, which goes to the heart of traditionally understood free press protections:

1. A media outlet has been sharply criticizing someone who until recently was a presidential nominee to high office.

2. Its criticism relates to alleged race discrimination by the person in his actions as essentially a private judge, within an important governmentally ratified system for regulating an important profession. (Note that FINRA decisions can be appealed to the Securities and Exchange Commission, a governmental body.)

3. There has been no trial finding the statements to be constitutionally unprotected defamation. Indeed, the injunction isn't limited to defamatory uses of the pictures, but includes uses that are simply expressions of opinion (as many accusations of figurative lynching will be).

4. There has been no trial finding that the statements are constitutionally unprotected true threats against Brummer. Indeed, they appear to be claims that Brummer is a lyncher, not that he should be lynched or otherwise violently attacked. There was one comment posted on a post at the Blot, which read, "These FINRA motherfuckers ruin lives! Fuck them or shoot them? Both perhaps." But there has been no trial finding that the comment was posted by the defendant; and I don't think that the presence of the comment makes the images into constitutionally unprotected "true threats" of violence.

5. There has been no trial finding that the statements are constitutionally unprotected "incitement[s] of violence." The "incitement" exception has been expressly and deliberately limited by the Supreme Court to speech that is (a) intended to and (b) likely to (c) lead to imminent criminal conduct (with imminent basically meaning within the next few hours or days, rather than at some unspecified point in the future). See Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969); Hess v. Indiana (1973). There appears to be little evidence that these three prongs of the incitement test are satisfied as to these images. Even if they "encourage lynching" (and I don't see how they do), that alone isn't enough to make them unprotected incitement. But the injunction goes further and bans any "images depicting … lynching in associate with plaintiff," and that certainly goes far beyond unprotected incitement.

6. To be sure, the Blot is tabloidy, hyperbolic and over-the-top. The posts may well prove to be defamatory at trial. They are certainly racially charged. None of us would want any such material to be written about us. But none of that can justify the injunction involved here, just as the tabloidy, hyperbolic, over-the-top, likely defamatory and overtly anti-Semitic content of the newspaper in Near v. Minnesota (1931) didn't justify the injunction in that case. (To be sure, that injunction was broader than the revised one, since the Near injunction closed the entire newspaper; but First Amendment law bars injunctions against particular statements and images as well as against entire publications, at least unless those statements and images are specifically found to fall within a specific First Amendment exception at trial - something that hasn't happened here.)

Now I think that the injunction here would have been unconstitutional even if it covered an individual speaker, rather than an online tabloid, or even if it was limited to speech about an ordinary citizen rather than about a recent nominee to high federal office. But the facts of this case just show what a strong and clear First Amendment case the publisher has. I don't recall a single appellate decision in recent decades that has allowed an injunction against words or images on facts such as this. I understand that an appeal is planned, and I hope that the New York high court - or, if necessary, the U.S. Supreme Court - will reverse the injunction outright or at least issue a complete stay of the injunction.

Today, this injunction just applies to the Blot, Brummer and the use of images of lynching. But if it's upheld, then similar injunctions could easily be issued against many other publications that criticize many other people (including public officials, public figures and professionals involved in matters of public concern) in many different ways. All it would take is some court concluding that the speech in some loose sense "encourage[s] the incitement of violence," or even just "depict[s]" violent conduct - with no showing that the usual First Amendment tests for incitement or true threats are satisfied, as they have not been satisfied for the speech prohibited here.

Show Comments (0)