Libertarian History/Philosophy

To Duke Historian Nancy MacLean, Advocating Free Markets Is Something 'The World Has Never Seen Anything Like…Before'

To some mainstream academics, libertarianism is too bizarre and hideous to even fit in their minds.

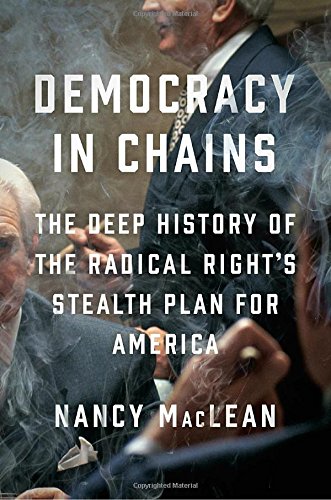

Duke University historian Nancy MacLean recently issued Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America, an alas quite hot book that purports to expose the dark secrets of Nobel Prize-winning economist James Buchanan and the "radical right"/libertarian movement he's allegedly the brains behind.

MacLean has been convincingly accused by many who understand his work and the libertarian movement with both less built-in hostility and more actual knowledge than she has (including me here at Reason) of getting nearly everything wrong, from fact to interpretation. She recently took to the Chronicle of Higher Education to allegedly reply to her critics.

A quick wrap up of many specific problems found in her book by her critics—by no means all—that MacLean ignores even while allegedly "respond[ing] to her critics," and which the editors at the Chronicle let her ignore:

• Her claim of meaningful similarity between John Calhoun's constitutional vision and that of Buchanan and his public choice school cannot be reasonably maintained.

• Her assertion that the modern public choice/libertarian constitutionalist vision has nothing to do with James Madison is not true.

• Buchanan did not, contra MacLean, believe that all taxation above voluntary giving is theft akin to a mugger in the park.

• She attributed to Buchanan the belief that those receiving government aid "are to be treated as subordinate members of the species, akin to… animals who are dependent" though he used that phrase to describe the attitude that was the opposite of his.

• Her attribution of Buchanan's use of the Hobbesian term "Leviathan" to (racist, uncoincidentally for her rhetorical smear purposes) Southern Agrarian poet Donald Davidson rather than, well, Hobbes, falls apart with study of when and how Buchanan began using the term in his work.

• She regularly cites libertarian thinkers as saying nasty things implying a contempt for the poor or for democracy that are not supported by the full context of the quotes; victims of her malicious misinterpretation including David Boaz and Tyler Cowen.

It's a pattern of hostile incomprehension, and her "response" indicates that this is partly because she's deep-down unable to view thinkers or funders who advocate limiting government's scope, expense, or power any other way.

MacLean speaks to none of the above specific critiques of her book in the Chronicle, merely generically complaining about being attacked and insisting that people who critique her work clearly hadn't read or understood it, or linking to people who sophistically defend some possible meanings in a manner far more subtle and complicated than she bothered to do.

Mostly eschewing factual or interpretational specifics, she reached instead for sympathy by complaining these specific critiques on her methods and understanding as a historian made her "feel vulnerable and exposed" and interpreting an intellectual metaphor for a physical threat.

She does a cute turnaround insisting against all evidence that those who praised her book were the only ones who read it, and that the very political forces she inveighs against in her book "helped create the current toxicity" allegedly exemplified by academic experts explaining how she got so many things so very wrong in her attempt to make her readers hate and fear anyone who wants to restrict government's power to manage our lives.

She certainly does not address a core problem with her book I detailed in my review: the "historical fact" upon which her entire thesis depends, her book's distinguishing selling point, which she claims to have uniquely discovered through diligent archival work, that James Buchanan was the secret influence behind the political funding machine of Charles Koch and that that machine is deliberately and conspiratorially disguising its libertarian goals, is completely invented. She creates an illusion of proof by citing documents that do not support the thesis in any way, shape, or form.

The most telling part of her defense in the Chronicle is how hard, well-nigh impossible, it is for her to imagine that people who might want the government to do less are actually a legitimate part of any public policy debate:

Sam Tanenhaus, in his otherwise favorable review in The Atlantic, said, "a movement isn't the same thing as a conspiracy. One openly declares its intentions. The other keeps them secret. It's not always clear that MacLean recognizes the difference." As a scholar, I understand the problems of conspiracy theories and while I never called this movement a conspiracy in the book, we do face a problem that our language has not caught up to our world.

In hindsight, I wish I'd said more about that in my book because we do not yet have a conceptual system adequate to capture what is happening….a messianic multibillionaire [has] contributed vast amounts of dark money to fund dozens upon dozens of ostensibly separate but actually connected organizations that are exploiting what Buchanan's team taught about "the rules of the game" of modern governance in a cold-eyed bid to bend our institutions and policies to goals they know most voters do not share….

….The world has never seen anything like it before; no wonder it's hard to find the right term to depict it. It's a vexing challenge to understand, let alone stop, and in hindsight I wish had been more explicit about that conceptual challenge….

What she is writing about is, yes, exactly what Tanenhaus called it: a movement. There is no need for her peculiar hyperventilating pretense that it's utterly unprecedented that donors and intellectuals in a democratic Republic would attempt to spread ideas or pass legislation in the direction of limiting government's expense or reach.

Despite her pretense that Buchanan is some secret linchpin to this movement, he always played a minor role in any kind of explicit policy terms (you wouldn't know it from this book but he explicitly eschewed reducing his high-minded constitutional musings to policy recommendations or political activism) in the loose association of free market thinkers dating back at least to the 1940s.

Had she known more about the history of free market and libertarian advocates and organizations since the '40s, she would have known that musing over various ways to actuate their goal of turning the culture more toward free markets have been consistent and often amount to nothing in particular, and cannot meaningfully be read as a secret conspiracy. The very fact that respected historians like MacLean can have this bizarrely uncomprehending attitude toward the libertarian movement is the very reason it needs to exist, and why it still fights an uphill battle.

When MacLean, for example, treats one particular 1973 memo from Buchanan skylarking about a "Third Century Project" to spread free market ideas as something of great significance, she seems to hope she's discovered another "Powell Memo," a 1971 memo written for the Chamber of Commerce by future Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell that similarly, and similarly in a long tradition, mused about how defenders of free enterprise could fight back in a world they (rightly) felt was rallied against them.

That Powell memo has also been overemphasized by academics dipping into the history of free market ideas as some secret origin of the modern right. It was just one more effort in a continuing, and still-fighting-for-air, movement to limit government growth. It only seems weird and secret to intellectuals of the mainstream or left because they don't know much about it.

That strong free market policies don't currently reign in the American public is exactly why an intellectual movement she considers sneaky and evil arose, to try to convince Americans both public and elite that liberty is the path to prosperity and peace. It is not destroying democracy to try to shape public discourse, even if MacLean doesn't like the way libertarians are trying to shape it.

Her belief that libertarianism is so inherently horrendous she is unable to conceptualize it as perfectly legitimate and totally predictable led to her kookoo public declarations of a deliberate organized conspiracy to discredit her—again without actually defending her work's credibility on any specifics—on the part of academics who are part of this, yes, movement.

On a personal note, while she states that her book is the "first detailed picture of how this movement began…and how it evolved over time" (see, using the word "movement" wasn't so hard there, was it?), she also cites my own book that does exactly that (Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement) over a dozen times.

For the most part, she does so reasonably and accurately. The one doozy of an exception is designed, unsurprisingly, to feed her "secret thesis" (one she spends a third of her book implying but never actually stating, so she can avoid having to explicitly defend it) that libertarian attitudes toward the state were essentially created by anger with the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education that desegregated public schools.

She cites to three pages of my book, and to other sources that similarly in no way support it, the idea that "Brown so energized this ragtag collection of outraged radicals of the right that some were no longer happy calling themselves 'libertarian.'"

Suffice it to say, nothing in the three pages of mine she cites, or the other sources in her cluttered endnote, support the contention that anything about Brown did anything to libertarians in the 1950s to make them question the term, or (outside of James Kirkpatrick, a right-wing segregationist fellow traveler) particularly motivate them in any way.

But that weird assertion is central to MacLean's purposes: making her readers think less of anyone who might want to restrict government power in a way she disapproves.

To baldly declare her real central point, which is that "I prefer, and I believe Americans prefer, more taxing and spending and redistribution than James Buchanan and libertarians want," would reveal her confused alleged historical epic as what it truly is: a hypertrophied polemical op-ed larded with often irrelevant smear and speculation, telling a story about James Buchanan that is neither true nor relevant to "the radical right's stealth plan for America."

Show Comments (361)