Five Lessons from the Hansa and AlphaBay Busts

Dark net market users can learn from the most successful cyber crime operation in the history of the internet.

It's been less than a week since a coalition of international law enforcement groups announced the successful takedown of the dark web's two largest drug markets, Hansa and AlphaBay.

We won't know for months—maybe longer—how many vendors and buyers around the globe will be raided, arrested, and incarcerated. We don't know—and might never know—if the Justice Department built its case using parallel construction, a method by which law enforcement agencies "recreate the investigative trail to effectively cover up where the information originated." We also don't know what other markets have been compromised.

All we know is that the Dutch National Police quietly seized a Lithuanian Hansa server in mid-June, copied the site, modified the code to collect data, and then ran the market normally for nearly a month. Then, on July 4, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) shut down Hansa competitor AlphaBay. Neither agency disclosed its actions until July 20. During that period, many users migrated from AlphaBay to Hansa, where the Dutch National Police were actively logging transactions and identifying both buyers and sellers. All told, the Dutch cops claim to have captured the physical addresses of 10,000 Hansa users. They are now sharing that data with law enforcement in other countries.

This is a teaching moment. Here are five lessons users of dark net markets can draw from the most successful cyber crime operation in the history of the internet:

1. The Justice Department grossly exaggerated fentanyl and heroin sales, but it still worked as a PR play.

The Justice Department's indictment of alleged AlphaBay founder Alexander Cazes references controlled buys of both drugs, and the agency's press release on the AlphaBay bust has the following subhed: "Dark Net' Site Was Major Source of Fentanyl and Heroin, Linked to Overdose Deaths."

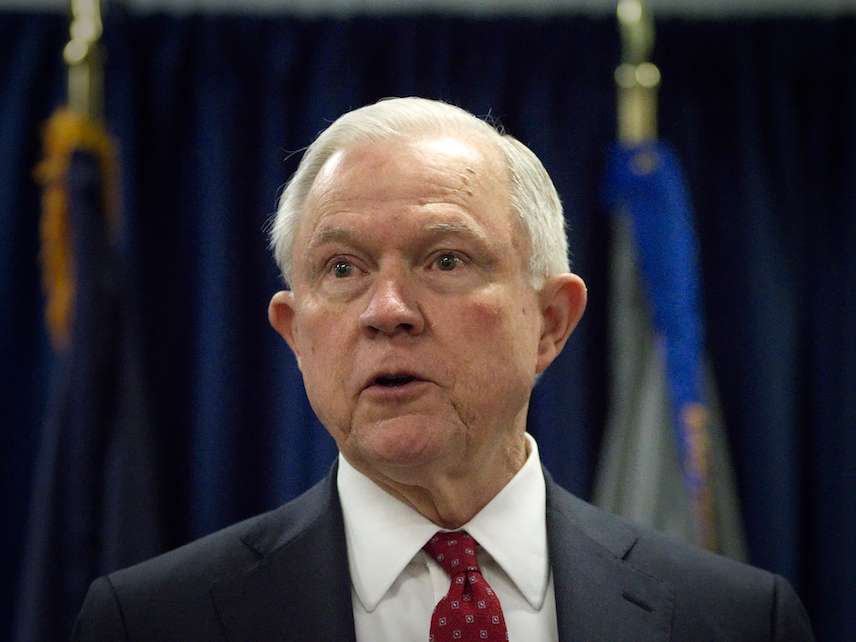

That claim is barely true. Of 40,000 drug vendors on AlphaBay, Attorney General Jeff Sessions claimed last week that fewer than 400—fewer than one percent—advertised the sale of heroin and/or fentanyl. The DOJ's press release references two U.S. overdose deaths linked to dark net markets. Two! Have there been more? Probably. But the dark net is not a major supplier of heroin.

Compared to offline drug markets, a recent report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) found that that heroin is actually underrepresented on the dark net. Dark net markets combine to make up less than 10 percent of global sales for all illicit drugs. Data from the Drug Enforcement Administration, meanwhile, show that most heroin consumed in the U.S. arrives via organized crime groups in South and Central America (which both grow poppies and import heroin from places like Afghanistan, which produces nearly 90 percent of the global heroin supply). The UNODC report says organized crime has a minimal presence on dark net markets.

While the claim is mostly false, the tiny bit of it that's true—dark net markets did facilitate some opioid sales, and some people overdosed as a result—works in favor of law enforcement, even if this bust does nothing to change overdose rates. Most of the reports on the bust that I've seen ran with the DOJ's claim. Would we see different media reports if Sessions had, more accurately, announced the takedown of a major supplier of marijuana, LSD, and MDMA? Almost certainly. Regardless, any site that hosts sales of opioids or opiates going forward will get short shrift from the media and a hard look from law enforcement.

2. Features that made it easy for laypersons to use dark net markets made it easy for law enforcement to find them.

Buying drugs on the dark net is not easy. You need to download the Tor browser, find the weird-looking .onion address for the market, buy and launder a cryptocurrency, and then arrange shipping. Each step is complicated, particularly if you want to obscure your trail. But AlphaBay and Hansa made the last step—the hardest step—way too easy.

To arrange shipping, buyers have to share instructions and a shipping address with a vendor. If operational security had been the highest priority, the sites would have required all users to set up their own PGP keys, which is a recommended best practice among encryption advocates. The buyer would post that anonymized public key in his or her user profile. The vendors and buyers would communicate by encrypting their own messages and using public PGP keys.

But that's a lot of steps for someone who just wants to buy a gram or two of cocaine, an ounce of marijuana, or a couple doses of LSD or MDMA. Hell, even the guy who invented PGP doesn't use it. So both Hansa and AlphaBay provided simpler options: Buyers could send the message containing their address completely unencrypted, or they could just check a box that allowed AlphaBay or Hansa to handle the encryption.

Messaging features meant to simplify the user experience enabled the Dutch National Police to immediately read all unencrypted messages stored on Hansa's server and to hack the vendor PGP option so that all messages could be decrypted and read before the vendor received them. That means any people who used Hansa after June 20 without using their own PGP setups to encrypt their addresses are now, or soon will be, a known quantity to law enforcement in their home countries.

3. Law enforcement groups are likely using drug forums to understand and execute operations.

Last week's indictment referenced Reddit, which hosts several forums dedicated to specific dark net markets as well as the dark net economy writ large. That police see Reddit as a valuable way to build a case isn't news; the feds sought to unmask five different users while prosecuting their case against Silk Road several years back.

But I suspect law enforcement took a very different tack in this operation. The day after AlphaBay went down, several Redditors encouraged users to migrate their business to Hansa, then under police control. It's entirely possible these posts were made by people who had used Hansa and found it to be a good site. But we also know that the Dutch National Police were watching the conversation and encouraged the theory that AlphaBay's proprietors had shut the site down themselves, which means it's possible the pro-Hansa posts came from dark net moderators or vendors who had already been detained and flipped by law enforcement.

We don't know for sure. But I wonder, going forward, how any user could confidently discern a well-meaning suggestion from a honeypot ploy.

4. Bigger markets are better right up until they're not.

The network effect says that markets become more valuable to their participants as they grow in size. The clearest example of this is Amazon, which is better in 2017 than it was in 2000 because it has more people buying and selling more stuff. It's also true of Facebook and Google. It was definitely true of AlphaBay, which had 250,000 drug listings, 40,000 vendors, and 200,000 customers at the time of its closure. At that scale, there's nothing you can't find at a reasonable price.

But huge networks have downsides. When Google experienced a five-minute server failure in 2013, global web traffic fell 40 percent. If we didn't already know it, the incident made many of us realize that web search had become largely centralized. Likewise, the unexplained disappearance of AlphaBay on July 4 sent dark net market participants into crisis. The site had become so big that the list of comparable alternative markets was tiny: Hansa, and a site called Dream, which may or may not also be compromised. (While there are other dark net markets, just as there are other search engines, they are smaller and less useful.)

Meanwhile, a giant illegal market presents a clearer target for law enforcement than a truly decentralized network of dozens or hundreds.

5. Law enforcement will let you buy things that are illegal in order to arrest you.

Upon Alphabay going down, users suggested a slew of possible explanations. Maybe it was an exit scam. Maybe it was a DDos attack on the AlphaBay servers. Maybe the cops had busted them. What no one considered was that multiple law enforcement agencies had shut down one market in order to herd users toward another market that they controlled.

Many Redditors initially expressed disbelief that the Dutch National Police had controlled Hansa for so long simply because they had received the drugs they ordered. How can the police sell me drugs? They didn't. They let users buy things so they could arrest them. Last year, my colleague Elizabeth Nolan Brown reported that the FBI may have controlled as many as half the dark net's child porn markets in order to identify and arrest child porn offenders.

This tactic isn't unique to the dark web. Many, if not most, federal drug cases are built by letting surveilled dealers do business over and over until they sell or traffic a total quantity that triggers a mandatory minimum. It's the same method used in the Fast and Furious gun-running case, in which the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms allowed U.S. gun dealers to sell firearms to straw buyers.

Just because you got away with buying or selling something illegal once—or twice, or even a dozen times—doesn't mean the cops aren't onto you.

Show Comments (27)