Newspaper Publishers Want Congress to Bail Them Out of Bad Investments

Not even Congress has the power to turn back that clock to the old days of publishing. Nor would anyone with any sense want it to.

It's the sort of brazen move that might ordinarily trigger a front-page news story or an outraged editorial—a bunch of very rich individuals asking Congress to write them a law that would give them better negotiating power against other rich individuals.

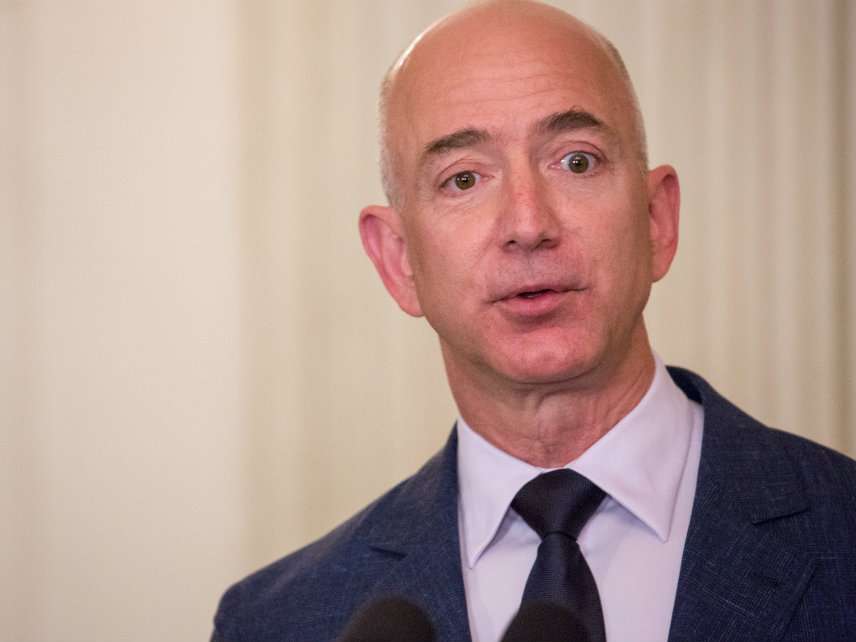

Yet in this case, the rich individuals wanting special treatment are the newspaper owners themselves. The Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos (worth $83.9 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaire's Index), The New York Times largest shareholder Carlos Slim (worth $61.1 billion), and Buffalo News owner Warren Buffett ($76.9 billion), publicly pleading poverty, are asking Congress for a helping hand in their negotiations with Google, controlled by Sergey Brin ($45.6 billion) and Larry Page ($46.8 billion).

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, the Bezos-Slim-Buffett front man, David Chavern, president and chief executive of the News Media Alliance, complained about what he called "an economically squeezed news industry." The Times, in a column sympathetic to the effort, likened the news providers to "serfs." Maybe Serf Bezos should have considered the economics of the news industry when he bought the Post, or Serf Slim when he bought his stake in the Times. The idea that Congress needs to roll to the rescue to bail "serfs" like Messrs. Bezos, Buffett, and Slim out of bad investments just doesn't pass the laugh test.

In respect of the Times, it's particularly comical, because, as an editorial matter, the paper generally favors stricter antitrust enforcement. The newspaper that less than two years ago was editorializing that Congress "should also study whether there are ways to strengthen the antitrust laws," now is backing the move for what its own columnist describes as "an anticompetitive safe haven," "a limited antitrust exemption."

One of Robert Bork's great scholarly insights was that if there's any logic to enforcing antitrust laws or enacting them in the first place at all, it is with a eye toward protecting consumers. The publishers make a case that news is a kind of special case because consumers are harmed by a decline in news quality. Or, as the Times quoted Chavern, "If you want a free news model, you will get news…But it will be garbage news."

I'm a paying, seven-day-a-week print newspaper subscriber who earns a living as a journalist primarily on the basis of people's willingness to pay for news. So I sympathize on some level with what Chavern is saying. But even I can see that his argument is, to use his own term, "garbage." Some excellent news—the CBS Evening News in its Walter Cronkite heyday, "60 Minutes"—is and was "free" to consumers, who paid with their willingness to be subjected to commercials. In this past election, the prediction model of the expensive, paid New York Times was just as wrong as that of the free Huffington Post. Nate Silver had a better prediction over at ESPN's free website.

Even if you buy the questionable idea that more expensive news automatically equals better news, it's a further, and even more tenuous, logical leap from that idea to the notion that Congress ought to interpose itself on one side of a set of business negotiations to make it easier for the publishers to make their news more expensive to consumers, or their ads more expensive to advertisers.

If publishers want to permit competing suppliers to negotiate prices and terms on a cooperative basis, then let them support changing the law to allow it in every industry, without special treatment for journalistic enterprises.

The Google-Facebook world has taken advertising and subscription revenue dollars out of publisher pockets. But it's been a huge boon to marketers and to readers. Advertisers can now reach targets more efficiently at a fraction of what they used to pay for print ads, and readers can now get news from a variety of sites and editors and journalists, from Matt Drudge to Mike Allen to Glenn Reynolds, rather than having to rely on the judgment of their one hometown newspaper editor. Not even Congress has the power to turn back that clock to the old days. Nor would anyone with any sense want it to, other than someone lucky (or unlucky) enough to have inherited a newspaper, or foolish enough to have overpaid for one.

Show Comments (40)