There's More to a Job Than Making Money

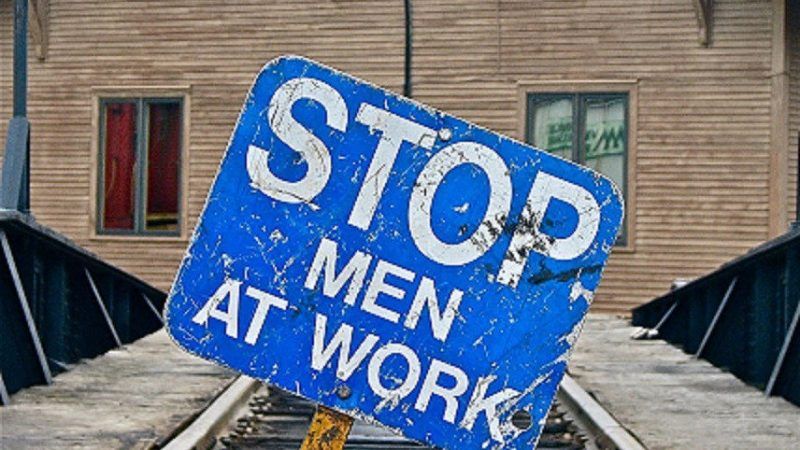

More than 11 percent of prime working-age men in the U.S. are outside the job market.

The most fundamental cause of economic poverty," said Richmond's 2013 poverty commission report, "is inadequate access to remunerative employment—that is, to good, steady jobs."

The absence of work causes other kinds of poverty, too. As Harvard economics professor Edward Glaeser points out in a new article for City Journal, "jobless husbands have a 50 percent higher divorce rate than employed husbands." The loss of a job inflicts a much greater degree of unhappiness than a reduction of income does. A loss of income likewise causes much less divorce, and much less suicide, than the loss of a job does. Jobs matter for reasons beyond money.

What's more: "Jobless men don't do a lot more socializing; they don't spend much more time with their kids. They do spend an extra 100 minutes daily watching television, and they sleep more. The jobless are also more likely to use illegal drugs. … 18 percent of the unemployed have done drugs in the last seven days."

Nicholas Eberstadt draws an even more finely grained and depressing picture in his book Men Without Work. He, and Glaeser, The New York Times, and many others focus attention on a dilemma no one seems to know how to fix. As The Times put it in a headline last year, "Millions of Men Are Missing From the Job Market."

In 1948, only 3.3 percent of prime working-age men (that is, those ages 25 to 54) sat outside the job market and did nothing. The rest were either working or seeking work. In 1967, the figure stood at about 5 percent. Today, it stands north of 11 percent. Fifteen percent of prime-age men are unemployed, including 28 percent of the college-educated and 59 percent of high-school dropouts.

Theories as to why abound. Liberals, naturally, gravitate toward structural explanations: de-industrialization has left men with no jobs to take. Conservatives blame structural issues of a different sort: excess regulation, changing social mores, an overly generous welfare state. "The unemployed tend to find jobs," Glaeser argues, "just as their (unemployment) insurance payments run out… Elementary economics tells us that paying people to be or stay jobless will increase joblessness."

Well. As Neil Gaiman put it in his introduction to Ray Bradbury's classic novel Fahrenheit 451: "If someone tells you what a story is about, they are probably right. If they tell you that is all the story is about, they are very definitely wrong."

De-industrialization has not really happened; U.S. manufacturing output has risen to record highs; the jobs have simply been replaced by automation. This has affected other advanced countries too, most of which have welfare states at least as generous as that in the United States. Yet America's prime-age-male idleness is generally higher than elsewhere.

Eberstadt notes that the withdrawal of men from the labor market has carried on largely indifferent to the business cycle, and Glaeser underscores the point with this datum: From 1976 to 2015, Nevada and Michigan had the highest and lowest rates of economic growth, respectively, "yet the two states had almost identical rises in the share of jobless prime-age men."

Making jobs more available might seem to be the obvious answer to joblessness, in the same way that making food more available might seem the obvious answer to hunger, but it is not so simple. Jobs, like food, are not scarce: The economy created 37 million service-sector jobs from 1980 to 2000 alone, for instance.

Perhaps men want to do manly work instead, such as construction? To that end, President Trump has proposed a massive new federal infrastructure program. But Glaeser notes: "Contemporary infrastructure projects rely on skilled workers, typically with wages exceeding $25 per hour; most of today's jobless lack such skills… And the nation needs infrastructure most in areas with the highest population density; joblessness is most common outside metropolitan America."

One answer might entail more skills training, through apprenticeships and vocational education. Roughly half of German students undertake an apprenticeship, and Germany also has among the lowest youth unemployment rates in the world. England, which had 50,000 apprentices two decades ago, now has a half-million. The U.S. has 100,000 fewer than England does, even though the Center for American Progress estimates it will need 5 million more workers with technical certificates than it is likely to have.

Another answer, frankly, probably entails faster rather than slower migration from rural areas—such as Virginia's coalfields—to places where jobs are plentiful. Government efforts to revitalize rural communities might merely delay the inevitable—and thereby prolong the agony.

In any event, it's clear that the current trend shouldn't continue. At least not unless you think the ideal America resembles a lions' pride—where the females do all the work, while the males lie back and enjoy the fruits of their effort.

This column originally appeared in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Show Comments (102)