How Washington Lost the War on Muscle

Steroid users hustle to stay one rep ahead of the law.

When Ned decided to try anabolic steroids for the first time, his goal was to "be bigger and look better." He had friends who used, and they seemed no worse for wear. The college sophomore was already training smart and eating right. "I felt like the pieces were in place to accelerate the process," he says looking back. That left the question of acquisition: He knew he could use the internet to illegally buy drugs from overseas, or he could invest some social capital in befriending a muscle-bound gym regular who might be able to hook him up. Still, he hesitated, until a fellow lifter revealed that he could obtain the same drug—testosterone, the paterfamilias of anabolic steroids—legally.

If Ned could convince an M.D. that he had low testosterone, he could walk away with script in hand. Then he would be able to pick up clean, accurately labeled "test" from his local pharmacy in broad daylight, instead of braving the black market. He'd avoid the risks of drugs passed hand-to-hand, which might be under-dosed, mislabeled, or dirty. And buying directly from an Indian or Chinese lab (which probably supplied the American gym vendor anyway) poses all those risks plus the additional possibility of criminal charges—including prison time—if U.S. Customs intercepts your package and conducts a "controlled delivery."

"I'd estimate the majority of controlled deliveries I've seen have involved quantities that are consistent with personal use," criminal defense attorney Rick Collins writes in Legal Muscle, his 2002 doorstopper on U.S. anabolic steroid laws. "A band of government agents will lie in wait until you make the horrific mistake of accepting your mail. Then, like a plague of locusts, they'll descend upon the sanctity of your home, ransacking it from roof to basement."

User surveys say that more than half of men who buy drugs for physique and performance enhancement do so on the internet black market, despite the fact that buying steroids without a prescription is a crime in every state and a federal offense. Yet those same surveys also suggest that the number of recreational steroid users who acquire their drugs legally may have tripled in the last 10 years.

What, exactly, are these people chasing? Some men want to look in the mirror and be blown away by their own sheer mass. Other men want to feel as virile and physically capable at 50 as they did at 18. Strength athletes—powerlifters and strongmen, professional and amateur alike—want to amplify their natural abilities. But contrary to popular media, the vast majority of steroid-using men are are not athletes, but regular working stiffs who like how they look and feel on "gear."

Ned, who asked me not to share his real name, is one of those people. He's happily married, employed in academia, and as conscientious about his health as he is about his appearance. He represents a growing demographic of people who are using internet message boards, publicly available research data, and licensed doctors to tweak their bodies, take control of their decisions, and build forbidden muscle in a post-prohibition world.

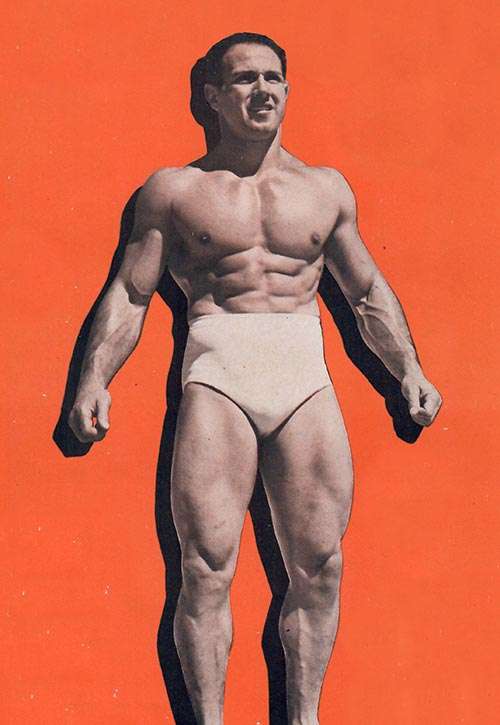

EXPERIMENTATION The use of anabolic steroids to build strength and muscle goes back to the middle of the 20th century and a company called Ciba Pharmaceuticals. Ciba conducted much of the early research into testosterone-based drugs, giving its compounds to American doctors and encouraging them to perform informal studies on their patients. The company published these findings in books such as 1948's Refresher Course on Male Hormone Therapy, which contains testosterone case studies for every condition then under the sun, from congenital eunuchoidism to same-sex attraction. (The eunuchs developed facial hair; the gay men thirsted even harder after other dudes.)

One of Ciba's doctors was the Maryland physician John Ziegler. According to his personal papers and records, obtained by Auburn University's John D. Fair for a 1993 report in the Journal of Sports History, Ziegler gave testosterone first to patients known to benefit from its anabolic qualities, such as burn victims. Testosterone's primary medical value is its ability to promote tissue growth. It increases red blood cell count, bone mineral density, and the number of satellite cells in muscle tissue. That means new skin for burn victims, bigger guns for lifters, and faster recovery for pretty much everyone. But testosterone is also androgenic: It stimulates the secondary sexual characteristics we associate with adult males, causing increased sebaceous gland activity and body hair, thickening of the vocal chords, prostate enlargement, and penis (or, in the case of women, clitoris) growth.

Ziegler likely knew about the anabolic effects, which is why he soon began giving the drugs to weightlifters at a gym in Silver Spring, Maryland, to see how the drug affected healthy people. This made him the first physician in the U.S. to administer testosterone not to repair, but to enhance. When members of the U.S. Olympic team attended the 1954 World Weightlifting Championships in Vienna, Austria, they did so with Ziegler in tow and Ciba's drugs coursing through their veins. It wasn't exactly an unfair advantage. Legend has it that Soviet lifters had been taking huge doses of testosterone for so long that their prostates were engorged and they needed catheters to urinate.

DEMONIZATION Three decades after steroids began to proliferate through the gyms of the developed world, "roid rage" became the new reefer madness. There was two-time Super Bowl Champion Steve Courson's 1985 Sports Illustrated interview, in which he said steroids wrecked his heart. Then Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson tested positive for the anabolic steroid stanozolol following the 1988 Summer Olympics, where he'd beaten the American phenom Carl Lewis in the 100-meter finals. In April 1989, Olympic sprinter Diane Williams tearfully described to a U.S. Senate committee how the steroids that made her one of the fastest women in the 1984 Olympics also made her clitoris grow uncomfortably large.

The Judiciary Committee report accompanying the 1990 Steroid Trafficking Act was chock full of still more anecdotal evidence that steroids were permeating every corner of American life: a mild-mannered cop in Oregon who began juicing and then shot a shop owner for no apparent reason, a normally happy teenager found dead of a suicide next to the weight set in his garage after three years of using, "an obsessed steroid user" who felt so empowered by the exogenous hormones pumping through his body that he asked a friend to film him as he drove his car into a tree at 40 miles per hour.

Until 1988, steroids could be purchased over the counter. Relatively cheaply, too, thanks to chemist Russell Marker's discovery in the 1940s that two types of wild yam indigenous to Mexico—barbasco and cabeza de negro—could be synthesized into sex hormones.

A few critics warned Congress against making steroids illegal. "The medical facts do not support scheduling," Edward Langston of the American Medical Association told a Senate committee in the spring of 1989. "First, anabolic steroids have an accepted use in the treatment of several medical conditions. Second, abuse of steroids does not lead to physical or psychological dependence."

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) also opposed adding anabolic steroids to the Controlled Substances Act. At a 1988 hearing, the DEA's Gene Haislip argued that steroids did not share the "principally psychoactive" quality of other scheduled drugs, and were mostly used "to develop muscles, to increase physical performance, and perhaps simply to look good and appear to be more attractive to the opposite sex." Haislip also didn't want to add to the DEA's workload. "We do, in fact, have our hands full with some other problems."

But both Congress and sporting bodies saw steroids as a problem. And so in 1990, when Congress added anabolic steroids to the Controlled Substances Act, they were put in Schedule III, rather than Schedule I or II. That's a crucial distinction, because unlike drugs labeled Schedule I—a category that contains marijuana, psilocybin, and LSD, among others—doctors can prescribe, pharmacists can sell, and patients can legally possess Schedule III drugs.

In 1988, domestic sales of legal testosterone were roughly $18 million, according to a 2002 Institute of Medicine survey. By 1999, the market was $100 million. Between 1999 and 2002, the number of testosterone prescriptions written in the U.S. each year more than doubled, from 648,000 to 1.75 million. From 2010 to 2013, the number of men filling testosterone prescriptions jumped from 1.2 million to 2.2 million. Today, the prescription testosterone market is worth more than $2 billion, and is expected to crest at $3 billion by the end of the decade. In its attempt to purge anabolic steroids from American culture, Congress paved the way for them to become an unremarkable fixture in the country's medicine cabinets.

MEDICALIZATION Abbott Pharmaceuticals' Androgel, released in 2000, was the industry's first successful attempt to market testosterone as a prescription drug for men with "low T." Thanks to those efforts (and the internet), the target audience of men in their 50s, 60s, and 70s can essentially self-diagnose with the help of the ADAM questionnaire. (ADAM is an acronym for Androgen Deficiency in the Aging Male. The list of questions includes "Are you sad or grumpy?" and "Are your erections less strong?")

Prior to Androgel's approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), testosterone deficiency was not a condition most Americans knew about. Nor did they know a doctor could prescribe them testosterone. Today, millions of Americans are on testosterone therapy—anabolic steroids by a less objectionable name—and the medical community is waging an internecine war over who should get it and why.

On one side are the restrictionists. In the April 2015 Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Thomas Perls of Boston Medical Center and David J. Handelsman of the University of Sydney deemed the "mass marketing of testosterone coupled with the permissive prescribing of testosterone for common, nonspecific, aging-related symptoms" to be "disease mongering." That same year, the FDA announced that "testosterone is being used extensively in attempts to relieve symptoms in men who have low testosterone for no apparent reason other than aging" and that "the benefits and safety of this use have not been established."

According to a drug use review commissioned by the FDA, 71 percent of the legal testosterone products sold in the U.S. between 2009 and 2013 were topical preparations such as Androgel, itself the best-selling testosterone product in the United States.

Whether or not all these men "need" testosterone is difficult to say, because the definition of who qualifies for the therapy varies by doctor and specialty. Most doctors now agree that testosterone levels in men decline with age, and that testosterone deficiency is comorbid with—meaning it occurs alongside and correlates with—other health problems, like obesity. There's even some evidence that American men are experiencing a generational decline in testosterone. But what should be done about these age-related declines, if anything, is a contentious topic.

A post-adolescent male's serum testosterone level is considered normal if a blood test reveals anything between 300 and 1,000 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dl). The Endocrine Society, the leading professional organization for clinicians working in hormonal medicine, takes the most conservative stance on testosterone prescribing. That means encouraging doctors to test their patients on two different days when the patient is healthy, since viral infections, sleeplessness, stress, and corticosteroids can all suppress testosterone levels. Any patient with serum testosterone levels at or even just slightly above 300 is "normal" under the Endocrine Society guidelines. Then again, so is a patient with testosterone levels that are three times higher.

Facing off against the restrictionists are doctors who take a broader view. "There is almost no other blood test that has that wide a range," says Abraham Morgantaler, a Boston urologist and faculty member at Harvard Medical School. An early pioneer of testosterone therapy, Morgantaler does not approve of giving it "for non-medical treatment," and he discourages patients from using testosterone he hasn't prescribed them. (Using two or more testosterone drugs simultaneously is called "stacking," and it's popular among bodybuilders.) Yet even with these stringent standards, he faces an uphill climb in convincing other doctors that "there's an enormous number of men who are walking around with undiagnosed testosterone deficiency."

"Most endocrinologists deal with diabetes and thyroid problems," Morgantaler explains. "That's 98 percent of their practice. They're unfamiliar and uncomfortable with low testosterone." That lack of familiarity may mean the average endocrinologist won't test for "free" testosterone (which is the amount of serum testosterone available for the body to use) or for androgen insensitivity (being less sensitive to androgens, says Morgantaler, means "if two people have the same testosterone levels, one of them will be fine, and the other will be symptomatic").

Some doctors will commence treatment for a patient who is on the low side of normal, and some will not. Some doctors will prescribe 200 milligrams of testosterone a week; some, like Morgantaler, believe it's unnecessary in most cases to exceed 100 mg a week; others will prescribe only 50 mg weekly. Some doctors encourage patients to use the gel preparation, while others only provide a patch, an implanted pellet, or injections. Of the latter, some use biweekly injections and some use weekly injections. Some doctors allow patients to inject themselves; others require an office visit. Some doctors will prescribe testosterone to women—who can also be deficient—while many more will not.

In short, testosterone-prescribing practices vary wildly. And that fractured landscape presents an arbitrage opportunity for recreational users who have done their homework.

MOTIVATION The best evidence we have that patients are using testosterone therapy for performance enhancement—what some doctors call "non-medical" use—comes from the patients themselves.

A 2007 survey of nearly 2,000 anabolic steroid users revealed both motivations for use and methods of drug acquisition. The study, published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, was conducted by psychologists Jason Cohen and Jack Darkes, criminal defense attorney Rick Collins, and pathologist Daniel Gwartney. The four men used steroid message boards, mass email lists, and muscle-magazine ads to recruit anabolic steroid users for an anonymous survey on what drugs they use and why.

The study, which had the largest sample size of any survey yet conducted of anabolic steroid users, found that 45 percent of respondents held at least a bachelor's degree and 83 percent were employed. Fifty percent made between $40,000 and $100,000 a year, and 25 percent made between $100,000 and $300,000 a year. More than 700 participants had jobs in banking, law, engineering, or computer science, while 112 worked in health care and 77 identified as members of law enforcement, as private security, or as first responders.

A study of 231 anabolic steroid users that was published by the Mayo Clinic in 2016 paints practically the same picture. "Most were white, were older than 25 years, were employed with above average income, and had received a formal education beyond high school," the authors wrote.

The users' motivations were not what we've come to expect from media reports about anabolic steroids. On a ranked scale, the Cohen study found that professional bodybuilding and professional sports were of little to no importance, while increasing strength, muscle mass, confidence, and appearance all ranked at the very top. ("Attract sex partners" was smack dab in the middle.) The Mayo Clinic study found similar motives.

Both surveys, along with a 2006 poll of 500 anabolic steroid users conducted by doctors at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), share the same inherent methodological weakness: While online surveys are an acceptable way to capture the sentiments of specific groups, they don't necessarily provide comprehensive data about everyone using steroids non-medically. Cohen and company could not "completely rule out" that "the use of an Internet survey strategy could have [led] to an over-sampling of those with higher education and socio-economic status."

The authors of the Mayo Clinic study write, however, that "the association of increasing age with higher incomes, being married, and being self-employed are also consistent with trends observed in the broader U.S. population (as indicated in 2010 U.S. Census data), which suggests that the current survey provides a demographically appropriate representative sample of the population."

Even in the absence of more conventional polling—which is difficult to carry out due to the legal status of many of these drugs—it's safe to assume that the vast majority of people who use steroids do so for the same reason another person might get plastic surgery, take a prescribed weight-loss drug, or join a gym: They want to feel better and to look better.

COLLABORATION Nearly half of all steroid users still buy drugs online, according to the Mayo Clinic, UCLA, and Cohen studies. But those reports also show a clear increase in prescription testosterone use. The UCLA doctors found that 11 percent of users get their testosterone from a doctor; in the Cohen study, the figure was 6 percent. In the Mayo study, conducted roughly 10 years later, nearly 28 percent were using prescription testosterone.

The rise among anabolic steroid users reflects the incredible role that the internet has played not only in providing men with access to illegal muscle drugs but also in educating them about how to obtain them legally. On dozens of online forums, steroid users have access to each other and to a wealth of clinical data going back decades.

There are threads dedicated to crashing your natural testosterone level in order to qualify for a prescription (getting drunk, barely sleeping, and using illegally acquired steroids will all do the trick). There are dosage instructions for "ancillary" drugs such as aromatase inhibitors, which block the conversion of excess testosterone to estrogen (the process by which steroid users develop gynecomastia, or "gyno"—an increase in glandular tissue under the nipple commonly called "man boobs"). There are discussions of post-cycle therapy, a timed cocktail of prescription drugs that restores natural testicular function. While the vast majority of the substances discussed in these forums have been extensively tested in human beings and are approved by the FDA, none of them were designed to benefit non-medical users of anabolic steroids. Men have pieced together their off-label usefulness over decades, drawing on peer-reviewed papers and on trial and error.

"I've used several different compounds, both as a responsible user and as an idiot teenager," says a D.C.-based software engineer who asked me to identify him as Matt, "and I've watched the underground knowledge of steroids blossom over the years with the advent of popular online communities that are geared toward performance enhancement." Forums like T Nation (the t stands for testosterone) and websites like PubMed, a clearinghouse for clinical research hosted by the National Institutes of Health, have been "key for recreational users like myself."

Matt started using steroids in high school while playing football. He continued to use them on and off for years—fathering two children with his wife between drug cycles—until complications from a vasectomy forced him to go on testosterone replacement therapy. "I ended up with a honeydew for a nutsack" after infection set in, he says. "Three months of missed work and two surgeries later, I had low testosterone."

Users like Matt have watched the muscle drug ecosystem evolve away from the "bro science" of the '80s and '90s and toward a collective research project focused on balancing the pursuit of an ideal physique with the desire to live a normal lifespan, start a family, and have a stable career.

"Before everyone was on the internet, you basically had to be in a hardcore powerlifting gym for months or years to find a connection. But the stereotypical gym dealer is a dying breed, and besides, these days most of those guys just buy the stuff online and then mark it up anyway." Meanwhile, people who want to know exactly what they're taking go to a doctor.

As a result of this shift to the web, where "lifetime users and lifetime researchers make themselves available," Matt says he and his compatriots are "much more informed and more concerned about learning how to use these compounds safely."

They share logs of their cycles—the length of time users are "on" steroids—documenting the changes in their appearance as well as side effects, such as acne, hair loss, and gyno. They share dosing regimens in search of feedback, and they challenge people to back up their claims with links to peer-reviewed research. Newbies are routinely told to have their blood tested before, during, and after their cycles, and teenagers are told to wait until they've reached full maturity.

The result is a pool of knowledge, both clinical and anecdotal, that far exceeds what most medical students learn about anabolic steroids during four years of medical school.

Yet there are still risks involved. Steroid users have each other, but they often lack professional medical guidance. In the 2006 UCLA survey, 91 percent of respondents said "they would prefer to use [anabolic steroids] legally under the direct supervision of a knowledgeable physician," but only 37 percent had ever discussed their drug use with a doctor. While the Mayo Clinic survey found that 69 percent of respondents regularly see a physician, participants weren't asked whether they disclose their steroid use during visits.

This remains the Achilles' heel of steroid prohibition. All three surveys found that most users take anabolic steroids in dosages that far exceed what a testosterone therapy doctor would prescribe, and are also likely using other muscle-building or weight-loss drugs, some of which—like the industrial chemical DNP, an ingredient in explosives—are categorically dangerous even in small amounts.

The majority of participants in each survey reported getting blood work done for their cholesterol levels, red blood cell counts, and liver health, something that's easier than ever in the age of private lab tests. But increased physician involvement would go a long way toward protecting user health. "I've done five cycles over the course of 10 years. In hindsight, I know that most of what I took was not safe, in the sense that I had no way of knowing what it was, whether it was 'clean,' whether the dose was correct," Ned, the academic who began using in college, wrote in an email.

Even still, it's hard to deny that the internet has made testosterone use both safer and more effective. In the process, the net has helped it go mainstream. Few people know that better than Chris Shugart, the chief content officer at T Nation and a leading voice for expanding testosterone access in order to provide "a safe and legal boost."

When he first started advocating for non-medical use of testosterone therapy, Shugart says the practice was "associated with steroid users, drug cheats, and 'roid rage.'" But today, "there are low-T centers and men's health clinics right next to Whole Foods and Super Cuts that routinely prescribe testosterone."

ACTUALIZATION Drug policy reformers almost never include muscle drugs in their reform agendas, perhaps because comparatively few people are busted for steroid trafficking. In 2015, federal judges sentenced 6,468 methamphetamine offenders, 6,166 cocaine offenders, 3,543 marijuana offenders, and 2,744 heroin offenders, but only 50 steroid offenders. That's 50 people too many, but it's not a number around which you can build a protest movement.

Ordering drugs off the black market poses a risk, regardless of how well-informed the buyers may be, but adverse reactions to anabolic steroids aren't a public health problem so far. Testosterone will never inspire the same cultural panic as, say, opioids, because the negative effects of testosterone use—arterial sclerosis, tumor growth, liver disease—tend to occur over years, if not decades, and only with certain compounds and dosages. Congress could mitigate those effects by rescheduling steroids and allowing doctors to prescribe them for non-medical purposes, but doctors aren't clamoring for that power and federal lawmakers have shown little interest in re- or descheduling anything.

As long as legal restrictions on steroid use remain, there will still be raids and arrests. The Justice Department will continue to add new formulations to the Controlled Substances Act just as quickly as chemists create them. Steroid users will still suffer bodily harm from dirty drugs and sloppy dosing protocols. In the absence of further clinical trials—highly unlikely since testosterone is off-patent—a divided medical community will continue to bicker about the safety and efficacy of the stuff even as millions of men use it.

But in a way, the war on steroids has already been won and the users are the victors. The internet is not going away, nor is the human desire to tweak and enhance the body. As we advance toward a future in which people are ever more modifiable, the things steroid users do will seem less strange.

Some once-potent arguments have already lost their luster. The mass proliferation of testosterone therapy has all but extinguished the idea that steroids make men uncontrollably violent. (With more than 2 million legal users roaming around, there should have been a noticeable uptick in violent crime if the stereotypes were true.) And the cultural objections about vanity are even less compelling. If the increase in Type II diabetes and other diseases associated with sedentary habits and junk food tells us anything, it's that Americans could stand to be far more vain about their bodies.

Steroid users have learned to think for themselves—to figure out what works for them and what doesn't; to weigh risks and rewards; and to aggressively investigate a lie that federal legislators had tried to push at gunpoint, in the idea that using steroids to get leaner and stronger would ruin their lives and compromise their characters.

Matt's occasional online purchases make him a criminal, but they have not made him less of a husband, a worse software engineer, or a bad father. Just the opposite, in fact: "Steroid use has motivated me to work out more, it's made me leaner, helps me sleep better and feel better. It's also kept my sex life very much alive and active," he wrote. "I have few regrets."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "How Washington Lost the War on Muscle."

Show Comments (73)