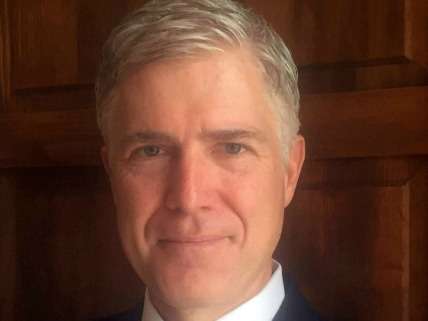

Judge Gorsuch's Natural Law

Trump's SCOTUS nominee is a natural law thinker. That's a good thing.

Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch isn't just a respected judge; he also holds a philosophy degree from Oxford, where he studied under John Finnis, one of the most prominent scholars in natural law theory. That may seem arcane, but Gorsuch's views about natural law set him apart from colleagues on the bench—and those differences may trouble not just liberals, but perhaps conservatives and libertarians, too.

Natural law is among the oldest philosophical traditions. Some of history's greatest geniuses, from Aristotle to Thomas Jefferson, devoted their most brilliant arguments to it, often differing about details but agreeing on the broad outlines. Natural law was the basis on which America's founders wrote the Constitution.

Among other things, it holds that politics isn't just a matter of agreement. Instead, principles of justice, or the idea that murder or theft are wrong, run deeper than government's mere say-so. Those things are actually wrong, aside from whether or not they are legal—and that means government itself can act unjustly and even impose rules that don't deserve the name "law."

That's a view many on both left and right share. The greatest spokesman for natural law in the twentieth century was probably Martin Luther King, who denounced segregation not because of its technical complexities, but because it betrayed the natural law principles of the Declaration of Independence.

But most judges today—including liberals and conservatives—reject natural law. They embrace a different view, "legal positivism," which holds that individual rights or concepts of justice are really manufactured government fiat. Even Justice Antonin Scalia rejected natural law arguments. "You protect minorities only because the majority determines that there are certain minority positions that deserve protection," he said, not because everyone has basic rights under natural law.

Still, even those who embrace natural law, including Justice Clarence Thomas, have their differences. For example, while Thomas and his allies see natural law as a basis for attacking legal protections for abortion and euthanasia—because they contradict the sanctity of life—others believe that natural law theory actually supports these rights, because it prioritizes individual autonomy.

That debate arises from a central natural-law question: What is the source of the good? Are things like life or freedom good because they relate to human purposes—such as the pursuit of a fulfilling life—or are they just intrinsically good, without any deeper reason? This debate matters because if life is just inherently good, then even someone suffering a terminal illness who wants to end his own life should be barred from doing so because life is good, period. On the other hand, if life is only good because it serves the goal of happiness, then someone whose life has become a burden of suffering should be free to end it if he chooses.

Oxford's John Finnis, and his student, Neil Gorsuch, embrace the intrinsic view: Life is just inherently good, full stop. In one scholarly article, Gorsuch argued that life is an "irreducible and categorical" good, not "instrumental or merely useful." Thus a person's "intent to die" should be off-limits, regardless of his suffering.

But this is misguided. The very notion of "good" implies an answer to the question "for what?" The correct answer is, for a flourishing life: It's why we eat, exercise, marry, or get jobs. Goodness is a function of our purposes. As philosopher Tara Smith writes in one criticism of Finnis, saying something is just an "irreducible and categorical" good isn't really an argument—it's just a bare assertion, or an "anti-theory," that "does not offer a justification of morality so much as a contention that no justification is needed." It's the equivalent of "because I say so."

Gorsuch's approach to natural law also indicates that he has a circumscribed view of individual choice, a subject that's always central to important constitutional cases, whether they be about abortion and euthanasia, or privacy and property rights. Justice Harry Blackmun put the point well when he dissented in the notorious Bowers v. Hardwick, which upheld state laws prohibiting same-sex intimacy. Courts, he wrote, protect individual rights "not because they contribute…to the general public welfare, but because they form so central a part of an individual's life. The concept of privacy embodies the 'moral fact that a person belongs to himself and not others nor to society as a whole.'" Many conservatives denounced that assertion, particularly Judge Robert Bork, an outspoken foe of natural law, who dismissed Blackmun's individualism as something that "can hardly be taken seriously."

In his 2006 book on euthanasia, Judge Gorsuch tries to take a middle ground. Echoing Finnis, he recognizes the importance of personal autonomy, but insists that government can "foreclose evil options without seriously infringing on individuals' opportunities" for self-determination. Thus he argues that terminal patients have a right to refuse medical treatment, but not to commit suicide, because in the former case he "come[s] to peace with death without necessarily having any intention to kill or help kill." That seems like a weak distinction, since we normally assume that a person who makes a choice, knowing the consequences, intends to cause those results. But it supports Gorsuch's ultimate conclusion that government can bar people from doing things it deems evil—just because—without actually violating their freedom of choice.

This isn't just an academic debate. Assisted suicide laws are now on the books in four states, and they've been challenged in the Supreme Court before. Sooner or later, the Court will review other laws, including abortion, medical marijuana, and the right to access medicine that has not been federally approved for sale. A person's natural right to make his own choices is at the forefront of all these questions. To take away his freedom just "because we say so" unjustly overrides his right to life. And while Gorsuch's philosophical opinions won't play the leading role in any court opinion on these subjects—such cases will focus mainly on legal and constitutional issues—all judges are influenced by their fundamental moral beliefs. After all, if the government can "foreclose evil options," that suggests the Constitution's protections for "liberty" do not bar the government from interfering with a wide range of personal decisions.

None of this is to say that Judge Gorsuch is a bad choice for the Court. On the contrary, while libertarians are likely to dispute his views of natural law, Gorsuch's views in this area are well within the mainstream of political philosophy, and his writings on these and other subjects reveal a deep commitment to ideas about justice and rights that are as important as they are timeless. Natural law thinkers may differ over important questions, but their debates play an essential part in our democratic and legal process—one many judges have ignored for far too long. As we choose someone who to help address some of our nation's most controversial questions, it's refreshing to see one candidate who takes these matters as seriously as they deserve.

Show Comments (207)