Barack Obama's Approval Rating Blinded Democrats (And Most Everyone Else) to Reality

He's a popular president, but most people said the country was on the wrong track and that's the key to understanding how Clinton lost.

Barring some major collapse over the next two months, President Barack Obama is likely to leave office with a higher approval rating than president-elect Donald Trump will enjoy on Inauguration Day.

On Election Day, Obama's approval rating sat at 56 percent, according to Gallup. He's been well above 50 percent for most of the past year.

As indicators for the outcome of elections go, that's supposed to be a pretty good one. Even as other signs pointed to an electorate that was unhappy—angry, even—at the status quo, at the political establishment, and at Washington, D.C., Obama's approval rating seemed to defy gravity and suggested that voters would support giving him a metaphorical "third term" in the form of Hillary Clinton.

We now know, of course, that it didn't work out that way.

Obama's sunny approval ratings are disconnected from how Americans feel about their government. According to the Real Clear Politics average, only 31 percent of Americans went into voting booths on Tuesday believing the country was on the right track—and that's actually a sunnier outlook than the electorate had earlier this year—a number that historically jives with voters tossing the president's party out of power.

Both major parties are to blame for Americans' pessimism, as both have done their fair share when it comes to driving up the debt, engaging in pointless foreign wars, and tying the economy in red tape.

One way to understand the outcome of the 2016 election, then, is as a distinction between the personality of Barack Obama and the policies of the federal government.

Polling guru Nate Silver identified that gap back in July. "We think the country is going to hell BUT we sorta like that Obama guy," is how he put it in a FiveThirtyEight chat on July 27. He warned at the time that presidential approval ratings are only "somewhat predictive" when the president isn't running for re-election (none of that stopped FiveThirtyEight, like pretty much everyone else, from predicting a Clinton win).

Clinton's team apparently didn't understand that distinction, and that warped perception of the race likely played a role in some of the questionable decisions they made in the final weeks before the election. Why was she spending time in Arizona during the final 10 days of the campaign instead of making a trip to Wisconsin (she didn't make a single post-convention campaign stop in Wisconsin), a state that was far more likely to influence the final outcome?

The only answer is that her campaign team believed they had an impenetrable "blue wall" and shifted their focus away from merely winning the election to trying to "expand the map." An easy Clinton win that turned Arizona blue—or came close to doing so—would play perfectly into a media narrative about Republicans losing their grip on traditionally red states with large Hispanic populations and the Clinton team wanted that narrative to be part of their perceived national mandate.

But she had no national mandate. She was an unpopular candidate promising to maintain the status quo of unpopular policies. No wonder people didn't flock to the polls to elect her.

The numbers are striking. Obama got more than 69 million votes nationally in 2008 (the most ever by a presidential candidate) and 65 million when he won re-election in 2012. Clinton managed just over 60 million votes on Election Day 2016, a 14 percent decline from what Obama got in 2008, despite an electorate that supposedly has grown more Democrat-friendly over the past eight years.

Trump will end up just north of 60 million votes, almost an identical total to what Romney got in 2012 and McCain got in 2008. If Trump grew the Republican Party at all, he did so at the expense of driving other GOP voters away (for good reason).

As Elizabeth Nolan Brown observed earlier this week, Trump won the election mostly because Clinton lost it.

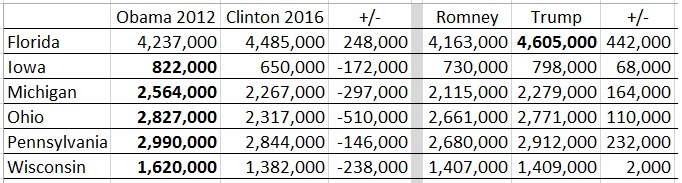

The election ultimately was decided by six states—Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—that flipped from blue in 2012 to red in 2016.

In five of those six states, Clinton fell short of Obama's 2012 vote total. Only in Florida did she outperform him. (A small percentage of votes are still being counted, but over 99 percent of precincts have reported in these six states)

Meanwhile, Trump outperformed Romney in all six swing states, but not by much.

Here's the real kicker for Democrats: compare Trump's column in the chart above with Obama's column. Clinton didn't have to grow the party at all. If she had merely maintained the same level of support enjoyed by Obama in each of those six states, she would have won five of them (Trump would have taken Florida) and would be president-elect.

Indeed, one of the few places where Clinton soundly outperformed Obama's 2012 vote totals was in Manhattan—cue Bernie Sanders' fans shouting "I told you so."

This is amazing -- Hillary received 23% more votes in Manhattan than Obama did in 2012. Perfect symbolism. pic.twitter.com/hNyh1xG9MO

— Michael Tracey (@mtracey) November 10, 2016

How to explain the disconnect between Obama's approval and the electorate's ongoing pessimism about the direction of the country? Perhaps Obama is a uniquely likeable politician in an age when we don't like many politicians. Maybe he benefitted from appearing to be above the partisan mudslinging of the nastiest campaign in recent American history. Maybe the role of the president as our celebrity-in-chief (something that predates Obama but a role that he embraced, and one Trump surely will too) creates a cognitive dissonance between voters' feelings about the singular person and the broader direction of the government.

Regardless, voters don't seem inclined to believe the idea of a metaphorical "third term" when they don't like the candidate being offered. Since the end of World War II, only Dwight Eisenhower and Bill Clinton, in 1960 and 2000, respectively, held higher approval ratings at their end of their terms than Obama does currently. Despite those high ratings, both Eisenhower and Clinton watched the opposite party capture the White House in close races.

Obama's high approval rating might have created a blind spot for the media, pollsters, and—most significantly of all—Hillary Clinton's campaign team. The country still likes Obama. That's not the same as liking the status quo.

Show Comments (108)