#VeteransForKaepernick, Compulsory Patriotism, Free Speech, and Dissent

Freedom of expression and a tolerance for ideas that might offend are American ideals worth fighting for.

I remember watching the 2001 Major League Baseball (MLB) playoffs, weeks after the devastating September 11th terror attacks killed thousands in my home city of New York (as well as hundreds more at the Pentagon and on United Flight 93, which crashed in a Pennsylvania field). The displays of patriotism during the games (and really, everywhere) were ostentatious, but understandable, as the country braced for a war against an enemy we clearly did not understand, with no idea that our response to the horrors unleashed the morning of 9/11/01 would beget horrors in Afghanistan and Iraq and elsewhere that have no resolution in sight a full decade-and-a-half later.

My friends and family each had suffered through the shock and grief of loved ones being wrenched from our lives in sudden and exceptionally cruel fashion. Lower Manhattan smoldered for months as the pile of buildings and bodies burned, emanating an unspeakably foul and unnatural stench the likes of which I had never experienced before but will never forget for as long as I live. The gash in the skyline was a constant reminder that nothing would ever be the same.

Everything stopped, including sports, for about two weeks. People wanted normalcy to return, but everything felt "too soon."

Still, eventually we had to try, and during those first few weeks after, baseball (particularly in New York) provided a venue for shared expressions of grief, unity, and even hope. The New York Mets played the city's first game after the attacks, which culminated in a stirring game-winning Mike Piazza home run that is still cited as an example of "the healing power of sports."

For the rest of the season, the pre-game performances of "The Star Spangled Banner" (a tradition started by the Boston Red Sox during World War I) were rousing, emotional, and cathartic. They frequently featured American flags big enough to fill an entire outfield, as well as special appearances by first responders who survived the collapse of the World Trade Center and family members of the fallen.

Prior to Game 2 of 2001 World Series played by the Arizona Diamondbacks and New York Yankees (who despite being widely-hated outside of New York became America's unlikliest sentimental favorites for that brief period), the national anthem was followed by a soulful and mournful Ray Charles performance of "America the Beautiful." Considering the context of the moment, you'd have to be a pretty hard-hearted person not to be moved by his rendition (to say nothing of the fact that it's a much better song than the "Banner"):

But that's the thing, these moments were special because they were unusual. They were rare. They would lose their meaning if they became expected and demanded displays of a unity which no longer existed, or of a shared patriotism which had become complicated by protracted and unpopular wars.

This is precisely what happened when "God Bless America" became a regular staple of baseball's 7th inning stretch.

In the weeks after 9/11, the performing of Irving Berlin's song was a moment for somber reflection. 15 years later, it's a gratuitous and maudlin interruption which 61 percent of baseball fans would happily do away with. Besides, after the pre-game national anthem, do fans really need to be subjected to what New York Daily News writer Gersh Kuntzman described as a "ponderous Mussolini-esque introduction of the song, when fans are asked to rise, remove their caps and place them over their hearts"?

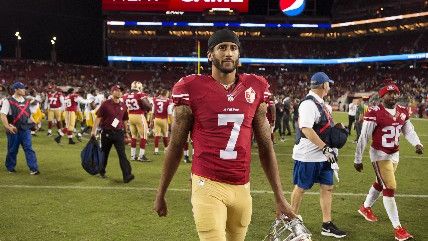

That's why the outrage over San Francisco 49ers backup quarterback Colin Kaepernick's hardly unprecedented choice to protest the socially-compulsory tradition of standing for the playing of the national anthem before a professional sports contest feels as forced as the tradition itself.

In response to his decision to sit out the anthem to protest police brutality and systemic racism in his country, the biracial Kaepernick (raised by adoptive white parents) was described by former New England Patriots safety Rodney Harrison as not black (or not black enough) to protest on behalf of black people. San Francisco's police union demanded an apology from both the National Football League (NFL) and the 49ers. The Blaze's Tomi Lahren called him a "whiner" and a race-baiter. Fox News' Sean Hannity speculated that Kaepernick might be a secret Muslim.

It is equal parts inexplicable and totally predictable that Hannity — who adores Donald "Make America Great Again" Trump — would take such exception to a rich person implying that America is not great. But whether or not one thinks Kaepernick's protest is opportunistic or disrespectful to the military, one can't argue with the fact that it is a peaceful and constitutionally protected protest, the kind that critics of Black Lives Matter protests insist are the only legitimate modes of expressing dissent.

It's silly to suggest that a marginal player's refusal to stand during a pre-game rendition of a song commemorating the military stalemate of the War of 1812 — and which features lyrics (albeit rarely sung lyrics) valorizing slavery — is somehow as much of an insult to American patriotism and military veterans as say, the NFL's acceptance of millions of dollars in taxpayer money for "paid patriotism" in the form of fighter jet flyovers and other military tributes that are never disclosed to the fans as the commercials for the military that they really are.

When Arizona Cardinals player Pat Tillman famously left a contract worth millions of dollars to enlist in the Army after 9/11, he was lionized as the living embodiment of selfless patriotism and masculine heroism. After he was killed by friendly fire in Afghanistan less than three years later, the NFL did everything it could to attach its image to his. But Tillman the man was harder to pigeonhole than Tillman the dead hero. He was a well-read political liberal and atheist who abhorred the war in Iraq (which he fought in) as "illegal and unjust" and "an imperial folly that was doing long-term damage to US interests," according to Jon Krakauer, the author of Where Men Win Glory, the Odyssey of Pat Tillman.

What if Tillman had lived? Would he have chafed at being used by the NFL and the Pentagon as a prop to sell a war he felt was unjust? What would the reaction have been had he decided to sit his heroic ass down during the national anthem to draw attention and support for the idea that he believed the war was wrong and should be stopped?

See, that's the thing, the military is not a monolith, and "heroes" are just people.

Take Jackie Robinson, the universally adored American hero who broke baseball's color barrier in 1947, and who also served in the Army during World War II (though he was never deployed to a combat zone). In Robinson's autobiography I Never Had It Made, the man whose number is the only one retired by all 30 MLB teams wrote of his experience standing for the national anthem during his first World Series game in his rookie season with the Brooklyn Dodgers:

There I was, the black grandson of a slave, the son of a black sharecropper, part of a historic occasion, a symbolic hero to my people. The air was sparkling. The sunlight was warm. The band struck up the national anthem. The flag billowed in the wind. It should have been a glorious moment for me as the stirring words of the national anthem poured from the stands. Perhaps, it was, but then again, perhaps, the anthem could be called the theme song for a drama called The Noble Experiment.

Robinson adds that despite his role in ending segregation in American sport, his reality trumped others sentimentality, and that for him, the anthem couldn't mean what others wanted it to mean for him:

As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.

Sure, Kaepernick's protest has offended many veterans and their families, and their feelings are not to be discounted. Kaepernick's right to freedom of speech does not grant him the right to be free of criticism.

But just as with Robinson, people are not defined by the images projected upon them, which can be seen through the #VeteransforKaepernick Twitter hashtag, where statements of solidarity with have come from veterans for any number of reasons.

Some explicitly support Kaepernick's motivations:

Because I'm a black woman in and out of uniform #VeteransForKaepernick pic.twitter.com/sBIhPQvmiB

— Liberation Brown (@LiberationBrown) August 31, 2016

#VeteransForKaepernick because I didn't volunteer to defend a country where police brutality is swept under the rug. pic.twitter.com/LtBkTvHHAn

— Baltic Avenue (@Baltic_Avenue) August 31, 2016

Some veterans don't want to be used as pawns in other people's political signaling:

Don't use my service--or that of any veteran--to justify the silencing of black Americans. Not on my watch. #VeteransForKaepernick

— Charles Clymer (@cmclymer) August 31, 2016

Or just his right to protest:

Free speech is free speech, all the time #VeteransForKaepernick pic.twitter.com/tOGOmYe0bC

— Coleman Chase (@colemanachase) August 31, 2016

Some just prefer not to be condescended by those who parrot "Support the Troops" when they really only mean "Support the Troops Who Agree with Me Politically":

Do not "support" me when convenient and do not assume that you know why I do what I do #VeteransforKaepernick pic.twitter.com/CSYF1SWAVP

— Immortal Ali (@Morris_Mann) August 31, 2016

Kaepernick says he has no plans to discontinue his silent protest at the 49ers' final preseason game tomorrow night in San Diego — a metropolitan area home to a large number of military bases and service-people — on the very night the San Diego Chargers host their "Salute to the Military." Expect the arguments over everything other than what Kaepernick's protest is actually motivated by to continue.

Show Comments (148)