Beverly Cleary at 100

Why Henry Huggins feels a little subversive today, and other stories of Klickitat Street

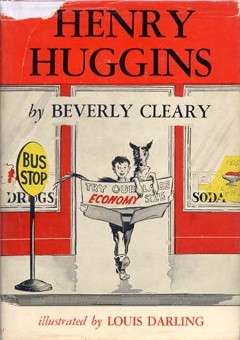

Beverly Cleary, who turned 100 yesterday, has written more than three dozen books for children over the course of her life. The most famous are her stories about Henry Huggins, Ramona Quimby, and the other boys and girls of Klickitat Street in Portland, Oregon. The earlier books in the series tend to be written from Henry's point of view, and the later ones from Ramona's; there is also one where the protagonist is Ramona's sister and one told from the POV of Henry's dog. Cleary, a librarian who dreaded didactic literature, started writing them because a boy asked where he could find books about "kids like us." I've read them all, in most cases twice: first as a boy in the late 1970s and early '80s, and then as a dad in the Obama era.

You notice a lot of things when you revisit your childhood reading three decades later. As an elementary schooler, I had found Cleary's books from the '50s enormously entertaining but also thought them a little square, as though they'd been dunked in a vat of Leave it to Beaver wholesomeness. (And indeed, Cleary wrote a few Leave it to Beaver tie-in novels too. I haven't read those.) The Ramona books had a more contemporary feel, with references to recent TV commercials and with plots that dealt with unemployment, shifting gender roles, and other weighty issues. But looking back now, it's the later books that sometimes feel a little behind-the-times, and not just because those commercials aren't so current anymore. In the '70s it may have seemed bold for Ramona's mom to become the breadwinner for a spell, but now we're more likely to notice how much housework still falls on her shoulders anyway (including some sewing tasks that a similarly situated family today might be more likely to outsource entirely). The '50s books, on the other hand, seem downright subversive, with all those little kids running around unsupervised so much of the time, launching elaborate projects without so much as telling a grown-up, let along asking permission. It's a wonder Henry managed to build that clubhouse without someone calling Child Protective Services on his parents.

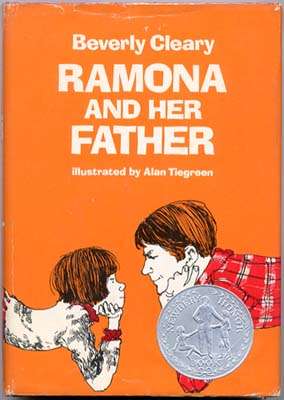

Don't get me wrong: I'm not knocking the Ramona books. Ramona Quimby is one of the great creations of 20th century children's literature, a character who comes across as a creature from hell when she's intruding into someone else's story but whose disruptive behavior makes perfect sense when you're seeing the world from her point of view. And there's a depth beneath her books' entertaining surface. Over the course of several novels, Ramona's father loses his job, has trouble finding work, takes a new job as a supermarket checker, hates it, pursues a passion by returning to college to become an art teacher, finds that he's unable to get a good job teaching art, and eventually goes back to working in a market. It isn't an utter defeat—he's a manager now, so he makes more money—but he still basically gives up on his dream. Cleary doesn't underline his disappointment; she just lets everything unfold, allowing her readers to see the compromises a lower-middle-class family has to make to get by. "We can't always do what we want in life," Ramona's dad says, "so we do the best we can."

It wasn't exactly a Hollywood vision, and it shouldn't be surprising that Hollywood didn't do a very good job of adapting it. Readers of Ramona Forever may remember all the little crises the family weathered while trying to throw together a wedding in two weeks on a not-infinite budget. In Ramona and Beezus, a recent film based on the series, they somehow manage to pull off the task in a couple of days, with no apparent difficulty and with no sign at the wedding itself that anyone had to stretch a dollar. And while Ramona's dad loses his job in the movie, he never has to settle for work at a supermarket: Without ever going back to school to study for a credential, he nonetheless gets a deus-ex-machina job offer to be an art teacher anyway. Where Cleary might end a book by letting the Quimbys enjoy a meal at Whopperburger, their troubles ongoing but their mutual support persisting too, the movie gives us a sitcom resolution to everyone's problems.

The Klickitat books may be Cleary's most famous creations, but they're hardly her only efforts worth reading. Emily's Runaway Imagination, my older daughter's favorite Cleary book, is set in the rural Northwest in the '20s; it makes the Henry Huggins stories seem hypermodern. Mitch and Amy offers a kid's-eye view of Berkeley in the '60s, with nary a revolutionary in sight; instead the focus is on bullying, homework trouble, and a school's latest high-tech audio-video equipment: a record player, a slide projector, and a screen. And then there's the Ralph Mouse trilogy, a rare venture into fantasy, featuring a talking mouse on a motorcycle. I especially liked Runaway Ralph, a thoughtful tale about a couple of nonconformists at a '70s summer camp, one of whom happens to be a rodent.

As a boy I just thought these were fun stories. As an adult I see the texture of the characters and the skill and wit with which their adventures are told. Some of the details may be bound to particular periods of the past, but as long as childhood still exists, Ramona and the rest should be recognizable.

(AUTHOR'S NOTE: After reading Ramona Forever again—this time to the other daughter—I have slightly altered the description of the book.)

Show Comments (20)