Utah's Anti-Polygamy Ruling Actually a Blow Against Free Speech

Brown family case was not about getting legal recognition from the state.

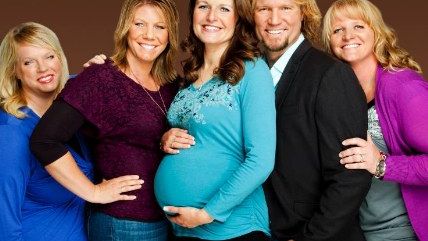

A federal court yesterday tossed out a lower court ruling that blocked the enforcement of a Utah law that criminalized polygamous relationships. Therefore, the the anti-polygamy law is back in effect. The case was brought by the polygamous Brown family made semi-famous in the TLC reality series Sister Wives. (Update: Wording cleaned up a bit to make the ruling clearer. Apologies!)

What actually happened is a little bit complicated. At no point during this whole process did a court rule that the state of Utah had to legally recognize polygamous marriages. That was not what this case is about at all. Rather, Utah has a law on the books outlawing married people from living with other partners and declaring themselves to be in a polygamous marriage. This was all completely separate from whether marriage licenses were even involved. This was a case about religious expression, freedom of association, and free speech, not government recognition or benefits.

But it was also a case where the Brown family was not actually being threatened with any sort of prosecution under this law. They were challenging the existence of the law as a violation of their liberties, but because the state of Utah was not threatening them with prosecution, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver ruled that the family did not have standing under the law and could not sue.

Beyond having a law that violates the right of adults to freely decide with whom to associate, the state's defense of having such a law, even though it was not charging the Browns for violating it, is creepy and horribly authoritarian:

State prosecutors have a longstanding policy against charging consenting adult polygamists, but attorneys argued in their appeal that the ban should stay on the books to help authorities go after those who commit crimes related to the practice, such as sexual assault, statutory rape and exploitation of government benefits.

Prosecutors pointed to imprisoned polygamous sect leader Warren Jeffs, who was convicted of assaulting underage girls he considered wives.

Presumably, Utah has laws against sexual assault, statutory rape and exploiting government benefits. Jeffs, by the way, was not actually convicted of violating this polygamy law, but of two counts of "rape as an accomplice."

We should be disturbed about the justification for keeping this law not just for the implications on free association and liberty, but the implications for the purpose of the laws themselves. The state's argument makes it implicit that the law itself is not intended to be enforced, but rather as something to throw at people when they violate laws that the state actually cares about. As a result, citizens end up living in a situation where enforcement of the law is ambiguous and unpredictable. Polygamists in Utah are fine until they do something else the state doesn't permit and then they may be punished for the polygamy as well. What that "something else" may be is up to the state, apparently. And while the state may say "Well, the Browns weren't actually prosecuted," The Washington Post notes that they were, in fact, being investigated for bigamy.

In a way, it's reminiscent of how laws against sodomy persisted all the way until 2003. Very few people actually wanted to charge or imprison people just for sodomy, which made it very hard to challenge the laws in the courts. The laws, though, could be used by prosecutors to threaten and cajole people over other crimes and force plea agreements. They are tools of intimidation. Under this logic, the state of Utah could declare anything at all illegal and avoid having to address constitutional violations by never actually charging anybody with the crime. They sure as hell could threaten those who don't have the capacity to fight back like the Browns could.

While the ruling is against the Browns on a technicality and does not create any sort of precedent, it is nevertheless a blow against freedom of speech and association. The Cato Institute had filed an amicus brief in support of the Brown family. Read about Cato's argument here.

The case also dovetails with the activism of Detroit pastor Neil Patrick Carrick. He has been challenging Michigan's marriage laws, which appear to criminalize "solemnizing" any marriage that is not recognized by the state. The law is unclear as to whether it is referring to marriages where the participants intend to seek legal recognition. Carrick sued to argue that he has the right to perform private marriage ceremonies for consenting adults who may not be looking for "official" recognition. Carrick's case ended just like the Brown case. Carrick was not actually charged with violating the law, and so a judge ended up tossing his lawsuit out due to lack of standing.

The Brown family said they plan to appeal this ruling.

Show Comments (25)