The Dying of the Poor White Americans

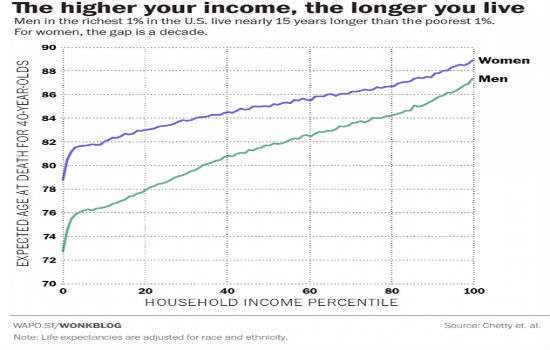

The gap in life expectancy between the top and bottom 1 percent of income for American men is nearly 15 years. For women, it's 10 years.

"Cirrhosis didn't kill her, being poor did," explained my cousin Sue about our cousin Teresa who died in her mid-40s more than a decade ago. Teresa, a vibrant personality who enjoyed drinking her beer, spent most of her life in small town eastern Tennessee. Sue believes that had Teresa been richer with better health insurance that she might have qualified for a liver transplant.

My cousin Myra also died in her early 40s. Myra, who weighed over 300 pounds when she succumbed to heart failure, lived in all her life in small town southwestern Virginia. Their sad stories turn out to be part of an alarming trend of rising death rates among rural poor white Americans.

I cite the sad premature deaths of my cousins as illustrations of the findings in two terrific articles in today's Washiington Post. On the front page is "A New Divide in American Death," and inside is an article, "Where living poor means dying young." The second article is reporting the results from a new study, "The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014," just published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

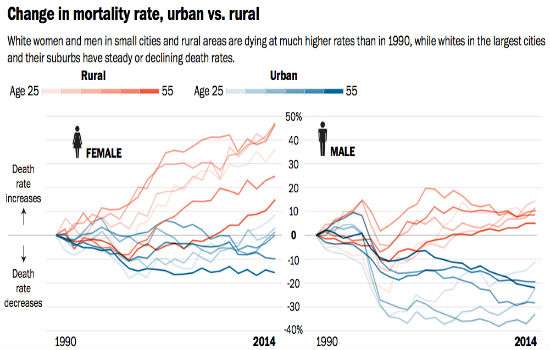

In the New Divide article, the Post reports:

White women have been dying prematurely at higher rates since the turn of this century, passing away in their 30s, 40s and 50s in a slow-motion crisis driven by decaying health in small-town America, according to an analysis of national health and mortality statistics by The Washington Post.

Among African Americans, Hispanics and even the oldest white Americans, death rates have continued to fall. But for white women in what should be the prime of their lives, death rates have spiked upward. In one of the hardest-hit groups — rural white women in their late 40s — the death rate has risen by 30 percent.

The rising death among poor rural white women appears to result from a combination of opioid and alcohol abuse, increased obesity, and rising suicide rates.

The second article based on the JAMA study also finds that the death rates for Americans vary by geograpy. Death rates are higher in small town and rural areas but also in hollowed out Midwestern rustbelt cities and in the Deep South. One of the more striking results is the gap between the top and bottom 1 percent of income for men nationwide is nearly 15 years. For women, it's 10 years. And these disparities have widened since 2000.

From the JAMA abstract:

The analysis yielded 4 results. First, higher income was associated with greater longevity throughout the income distribution. The gap in life expectancy between the richest 1% and poorest 1% of individuals was 14.6 years (95% CI, 14.4 to 14.8 years) for men and 10.1 years (95% CI, 9.9 to 10.3 years) for women. Second, inequality in life expectancy increased over time. Between 2001 and 2014, life expectancy increased by 2.34 years for men and 2.91 years for women in the top 5% of the income distribution, but by only 0.32 years for men and 0.04 years for women in the bottom 5% (P?<?.001 for the differences for both sexes). Third, life expectancy for low-income individuals varied substantially across local areas. In the bottom income quartile, life expectancy differed by approximately 4.5 years between areas with the highest and lowest longevity. Changes in life expectancy between 2001 and 2014 ranged from gains of more than 4 years to losses of more than 2 years across areas. Fourth, geographic differences in life expectancy for individuals in the lowest income quartile were significantly correlated with health behaviors such as smoking (r?=??0.69, P? <?.001), but were not significantly correlated with access to medical care, physical environmental factors, income inequality, or labor market conditions. Life expectancy for low-income individuals was positively correlated with the local area fraction of immigrants (r?=?0.72, P?<?.001), fraction of college graduates (r?=?0.42, P?<?.001), and government expenditures (r?=?0.57, P?<?.001).

In an accompanying editorial, Economics Nobelist Angus Deaton notes that the differences in income could arise from the fact that people who have good health earn more. He further observes:

It is as if the top income percentiles belong to one world of elite, wealthy US adults, whereas the bottom income percentiles each belong to separate worlds of poverty, each unhappy and unhealthy in its own way. The life expectancy at 40 years of age in the top income percentile of the United States is better than the mean in any other country for life expectancy at 40 years of age. However, not by a lot, and likely not better than the top percentile in Sweden or the Netherlands. In contrast, the life expectancy at 40 years of age in the bottom income percentile of the United States is located between the mean for Pakistan and Sudan for life expectancy at 40 years of age.

For more background, see my article, "Poverty Is Deadly."

Show Comments (264)