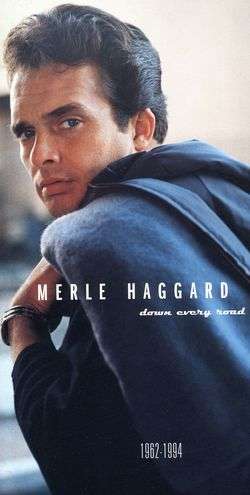

Merle Haggard, RIP

A great American voice has died.

Fifty-nine years ago, two men and a woman sat around a table in Bakersfield, drinking red wine and cursing the state of the union. "Ain't no jobs to be had," one man said.

"I know it, I know it," said the other. "An honest man might's well quit trying." And then he added: "I know where there's a bunch of money. It wouldn't be no trouble to get it."

The trio, now thoroughly drunk, decided to break into a restaurant on Highway 99. No one would catch them, they reasoned, because it was 3 in the morning. And so they headed out to the roadhouse with a baby in tow, and they started trying to pry their way in through the back door.

Unfortunately for the crooks, they had been too drunk to read the clock correctly: It was actually around 10 p.m., and the joint was still open. And that was how Merle Haggard, who had already spent more than a little time locked up for a variety of petty offenses, got a ticket to San Quentin.

It was in that prison, inspired by one of Johnny Cash's concerts-behind-bars, that Haggard the inept burglar decided to turn his life around. We're all fortunate that he did. In the time since he left San Quentin in 1960, Haggard—who died today on his 79th birthday—built one of the richest bodies of work in the history of American popular music. A country singer, Haggard was always happy to draw as well from other genres: blues, rock, gospel, and especially jazz. (The next time you watch that famous clip of Bing Crosby and David Bowie singing an odd-couple duet, remind yourself that Haggard was a professed fan of both.) He was an excellent vocalist, a capable guitarist and fiddler, and the leader of an expert band. But he wasn't just a musical giant. His finest songs are tightly compressed stories and character sketches that belong in the canon of American literature.

How much do his best records stand out? Country music is full of songs about truck drivers, but I can't think of any as world-weary and bleak as "White Line Fever," with its aging narrator's lament: "I've been from coast to coast a hundred times or more/And I ain't found one single place where I ain't been before."

The song treats truck driving as an addiction, and when you combine that with the phrase "white line" you may suspect the verses have a hidden second subject. Decades later, Haggard would begin another world-weary song—"Wishing All These Old Things Were New"—with an explicit reference to that other sort of white line: "Watching while some old friends do a line/Holding back the want-to in my own addicted mind." And then, in the second verse, a moment with more than a hint of autobiography: "Watching while some young men go to jail/And they show it all on TV, just to see somebody fail." Listen:

It's both nostalgic and anti-nostalgic—a song for someone who misses the old times but also knows damn well they weren't as good as he remembers them. This was a recurring theme for Haggard. (It should be no surprise that he recorded a version of Dolly Parton's "In the Good Old Days When Times Were Bad.") His most poetic expression of the idea may be a line from "They're Tearing the Labor Camps Down," a song about a man returning to his hometown and seeing that the camp where he used to work isn't there anymore. "I feel a little sentimental shame," he sings.

Haggard's most famous record—or infamous, in some circles—is "Okie from Muskogee," the Silent Majority's great culture-war anthem of 1969. At the time, people took it as a song for hardhats who hated hippies: Spiro Agnew mashed up with the Grand Ole Opry. Years later, it became common to claim the tune was intended as a joke. Haggard's latter-day lifestyle certainly made it easy to take it that way: When a man who smokes pot starts a song with the words "We don't smoke marijuana in Muskogee," you have to wonder whether he's speaking for himself. And Haggard undeniably enjoyed his pot. "Son," he supposedly said once, "the only place I don't smoke it is Muskogee!"

Haggard himself was always cagey about what he meant by the song, and the answers he gave to interviewers weren't always consistent with one another. But the best way to understand the record, I've long thought, is to take it as a dramatic monologue. "Okie" reports how a conservative character feels about the counterculture, and whether you take his views as inspiring or hilarious is up to you. The fact that it can work either way is a tribute to Haggard's skills.

It could be hard to get a bead on Haggard's politics. After "Okie from Muskogee" was a smash hit, Haggard wanted his next single to be "Irma Jackson," an anti-racist story about interracial love. His label rejected the idea—indeed, it refused to release the song at all for several years—and his follow-up instead was "The Fightin' Side of Me," a ditty about wanting to beat up anti-American protesters. That one could've been the soundtrack to the Hard Hat Riot of 1970, when rampaging construction workers in New York attacked hippies and demanded that City Hall raise the American flag. (Though even here, the politics aren't as simple as you might assume: The singer stresses that "I don't mind them switching sides and standing up for things that they believe in" before explaining that it's "when they're running down our country" that "they're walking on the fighting side of me.")

Haggard's politics got only more unpredictable as he grew older. By the late '90s he was spouting militia-style conspiracy theories and calling for the legalization of weed. In the Bush years he took to denouncing the president as one of "the top three assholes of all time" (along with Nixon and Hitler) and harshly criticizing the Iraq war. ("Why don't we liberate/These United States?/We're the ones who need it the worst," he sang in 2005. The track was called "America First.") In 2008, he wrote a number endorsing Hillary Clinton for president—not one of his most accomplished compositions, though I can't help admiring his ability to fit the line "What we need's a big switch of genders" into a country song. Or maybe I should say he seemed to endorse Hillary: Not long after he wrote it, he went on the Bill Maher show and defied common sense by denying that the song—which builds to the line "let's put a woman in charge"—had been an endorsement. ("I simply wrote a song that said she would be the best buy," he grinned, prompting Maher to comment that Haggard was "parsing it closer than Bill.") Haggard was large. He contained multitudes.

And so did his catalog. It's not just that he wrote so many wonderful hits, from "Mama Tried" to "Silver Wings" to "Big City." Even his obscure compositions could be gems, from the delicate, Blackbirdesque beauty of "The Day the Rains Came" to the blunt paranoia of "Lonesome Day." He was a master interpreter of other people's words too: It was Hank Cochran and Red Lane who wrote "I'll Be a Hero When I Strike," a haunting portrait of an assassin, but the skittish, apprehensive delivery here is all Haggard:

With so many brilliant entries in the Haggard songbook, I'm not sure I could pick a single favorite. But if I had to choose one, it would probably be "Sing Me Back Home," a superficially simple account of a prisoner singing one last song to another convict before the latter is led to the executioner. There are no inspired metaphors or bursts of clever wordplay here, but the song feels infinitely complex; we hear a memory within another memory, and somehow, in the spaces between the chorus and the song's two verses, we feel the weight of a man's entire life. If it isn't Haggard's best song, it's surely the one with which to mourn him:

Show Comments (143)