LAPD Commissioners Push for De-escalation Training. Naturally, Police Union Pushes Back

Union president calls clarified rules on use of force a "a no-win situation for the officer."

The LAPD Police Commission, a civilian review board

that works with the Chief of Police to oversee the department and help set policy, voted unanimously yesterday to implement new "use-of-force policies that emphasize de-escalation and the use of minimal force in encounters with the public."

The proposed rules were born out of a two-year effort to examine how departmental policy and officer training changed over the past ten years. In 2014, Inspector General Alexander Bustamante released a 22-page report on the LAPD's Categorical Use of Force Policy, which led to the Police Commission's release of a subsequent report last week that included 12 specific recommendations to changes in policy.

Some of the proposed changes include:

-Only using deadly force when "reasonable alternatives have been exhausted or appear impracticable."

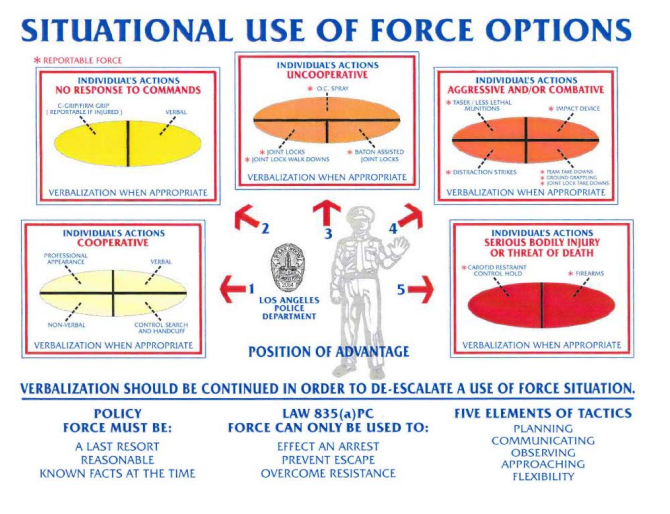

-Officers are expected to "redeploy to a position of tactical advantage when faced with a threat, whenever such redeployment can be reasonably accomplished in a manner consistent with officer and public-safety."

-Officers assigned to units that patrol places like L.A.'s notorious Skid Row, will be required to undergo "specialized training prior to engaging in any enforcement action with the mental health or homeless community."

That last recommendation is particularly relevant in light of a recent report from the Ruderman Family Foundation indicating nearly a third of all people who die at the hands of law enforcement are afflicted by a disability.

At Tuesday's hearing, Commission Chairman Matthew Johnson said, "There are unfortunately incidents where an officer simply does not have the time necessary to de-escalate a situation; sometimes the threat is too immediate, the potential injury to others or the officer is too great," but Johnson added, "When there is time, we should never take a life when we have the option of resolving the situation without doing so."

According to LAPD Chief Charlie Beck, de-escalation training has been increasingly prioritized over the past few years but that the Commission's new mandate "makes it a point of discussion in the deliberations and in the investigations of use of force." Beck added the department wants "smart cops" with the ability to "think critically" and that he didn't see anything in the proposed policies that the union couldn't "buy-in" to with "the right discussion and the right folks at the table."

Beck may be engaging in willful thinking, as both the president and director of the LAPD's union, the Police Protective League, have already come out against the changes. Union Director James McBride told the Commission that if an officer were killed because he/she hesitated as a result of a new use-of-force policy "there will be blood on your hands."

Union President Craig Lally, once named a "problem officer" in a blue-ribbon panel's report on "the problem of excessive force in the LAPD" following the 1991 beating of Rodney King, said the new policies create a "no-win situation for the officer."

Lally added that if faced with a potentially violent situation, "The best way to de-escalate is to run away:"

The officers should just arrive there, look at the situation, see a gun or a knife and say, 'You know what, I'm going to get blamed if I shoot.'

Whether it's totally justified or not, they're going to get reamed, they're going to get second-guessed.

Pushing back on any reforms, even ones endorsed by their own police chiefs, is standard operating procedure for police unions. Maryland's Fraternal Order of Police recently rejected outright the proposals of a state commission charged with improving community-police relations following the death of Freddie Gray, who died after his spine was severed during a rough ride in the back of police van, and the social unrest that followed.

Police unions present a particularly difficult quandry when it comes to reform, because Democrats are loathe to be seen as inhibiting the power of public sector unions and Republicans have leaned on a "tough on crime" posture for decades.

The upside is that a number of large American cities have already begun to de-emphasize military-style techniques to policing, helping officers to learn to see themselves as "guardians" of the public rather than "warriors" in an occupied country.

Show Comments (45)