Does Anybody Believe the FBI Isn't Out to Defeat Encryption?

The talking points insist this Apple case is an isolated incident. Evidence suggests otherwise.

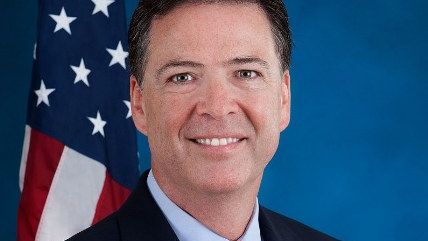

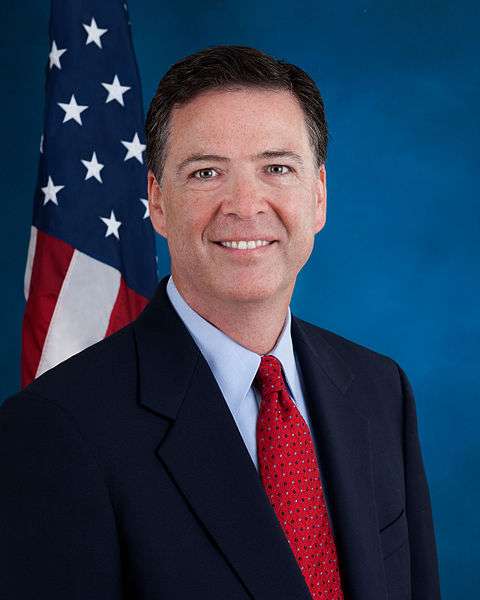

FBI Director James Comey starts his defense of their effort to force Apple to help them break into the iPhone of San Bernardino terrorist and killer Syed Farook with a sentence that is that is extremely hard to take seriously: "The San Bernardino litigation isn't about trying to set a precedent or send any kind of message."

That's from a Sunday contribution on the Lawfare blog, focusing on the same talking points we've been hearing from the feds since a judge last week ordered Apple to take some actions that would make it easier for the FBI to brute force the passcode into Farook's phone. Comey insists that what the FBI is asking for is very narrow and is not about breaking encryption or creating a "master key" to force back doors into encryption.

There are also plenty of appeals to emotion to try to make people feel bad for resisting their efforts. The title of the post is "We Could Not Look the Survivors in the Eye if We Did Not Follow this Lead," a sentiment repeated in the content of the short commentary

The problem with treating Comey's claim credibly is that we all know full well that the White House, the executive branch, federal law enforcement, and intelligence are all united in a concerted effort to do pretty much the opposite of what Comey says: to find ways to break through encryption. Bloomberg got its hands on a memo from a strategy meeting from last Thanksgiving that showed that what Comey is doing here is exactly the White House's plan:

The approach was formalized in a confidential National Security Council "decision memo," tasking government agencies with developing encryption workarounds, estimating additional budgets and identifying laws that may need to be changed to counter what FBI Director James Comey calls the "going dark" problem: investigators being unable to access the contents of encrypted data stored on mobile devices or traveling across the Internet. Details of the memo reveal that, in private, the government was honing a sharper edge to its relationship with Silicon Valley alongside more public signs of rapprochement.

The argument that accessing Farook's iPhone is an isolated request is very clearly a talking point planned well out in advance, and like many efforts that have come from the White House, we're seeing an obviously organized media blitz to sell it, to the point that they're overplaying their hand. The Department of Justice (DOJ) responded to Apple CEO Tim Cook's public statement warning against the FBI's demands with a federal court filing calling his concerns an effort to protect his "brand marketing." Apple hadn't even responded to the court's request yet. This was a public statement from Cook and Apple. And the DOJ responded with a court filing without even waiting to see what arguments Apple actually presented to the judge.

Cook is sticking to his guns, sending an email out to Apple employees telling them "Apple is a uniquely American company. It does not feel right to be on the opposite side of the government in a case centering on the freedoms and liberties that government is meant to protect." He wants the government to form a tech commission to discuss the privacy implications of what the FBI wants. And he reminds everybody of the obvious that Comey is hoping we'll ignore: That if the government is successful in forcing Apple to help them here, they can come back to the courts again and again and again to order them again and again and again. Comey's counterargument can be best paraphrased as "No, we won't," even though everybody knows full well they have a mission to defeat encryption.

In some other news related to the encryption fight, Donald Trump said that people should boycott Apple, which tells you everything you need to know about what Trump thinks of civil liberties (if you didn't already know he doesn't give a damn about them).

It also turns out the FBI wouldn't have needed to break into Farook's phone at all, Apple claims, if the FBI hadn't arranged to have Farook's passcode reset while the phone was in custody, which cut off the ability to back up the phone's contents to iCloud (The FBI responded that the iCloud back up doesn't collect all phone data, and they still would have wanted access to the phone from Apple).

Find the fight confusing? Read my explanation as to why this encryption fight is bigger than one terrorist's phone and how it could affect you here.

Show Comments (81)