Hurricane Joaquin: The Great East Coast Hurricane Drought Likely Continues

No sign yet that global warming is making hurricane damage worse

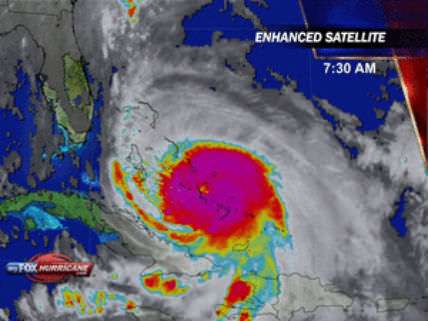

Hurricane Joaquin, currently spinning off the east coast of the United States, has been upgraded to category 4. Despite some earlier worries, the good news is that weather models are now predicting that the storm will likely not come ashore on the U.S. East Coast after all. This means that the great East Coast hurricane drought continues.

Earlier this year, researchers from NASA and the ACE Tempest Re Group reported that "the U.S. has experienced no major hurricane landfall since Hurricane Wilma in 2005, a drought that currently stands at 9?years." They further noted that this is the longest period in which no major hurricanes have come ashore in the United States, and they calculated that such an extended hurricane drought occurs every 177 years or so. (Major hurricanes are defined as category 3 and above, meaning that their sustained wind speeds exceed 111 miles per hour.)

Mid-Atlantic residents who suffered through Superstorm Sandy in 2012 might question the notion that there has been a hurricane drought since 2005. The storm surge and flooding produced by Sandy killed 72 people in the U.S. and caused more than $50 billion in damage. Nonetheless, when Sandy hit New Jersey and New York, it was no longer a hurricane.

In 2005, by contrast, we were hit by Katrina, Rita, Dennis, and Wilma. That year's hurricane season broke numerous records. Most tropical storms: 28. (Old record: 21, in 1933.) Most hurricanes: 15. (Old record: 12, in 1969.) Most category 5 hurricanes: 4. (Old record: 2, in 1960 and 1961.) Most property damage: $150 billion. (Previous record: approximately $50 billion—in 2005 dollars—in 1992 and 2004.) After wild season like that, a hurricane drought was a welcome phenomenon.

In August, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration forecasted a below-average season for 2016, featuring 6 to 10 named storms, 1 to 4 hurricanes, and 0 to 1 major hurricanes. Excepting Joaquin, so far this year has seen 8 named tropical storms and two hurricanes. This is well below the annual average of 11.7 tropical storms, 6.3 hurricanes, 2.4 major hurricanes, 1.7 U.S. landfalling hurricanes, and 0.6 major landfalling hurricanes.

In 2005, one widely reported study found that globally, the number category 4 and 5 hurricanes had doubled since 1970. Taking an additional 10 years of data into account, a 2015 study in the Journal of Climate now finds instead that the "global frequency of category 4 and 5 hurricanes has shown a small, insignificant downward trend." One comprehensive measure of tropical storm activity is accumulated cyclone energy, which calculates the destructive power of storms by taking into account their sustained wind speeds. The 2015 Journal of Climate study reports that accumulated cyclone energy has experienced a large and significant downward trend globally since 1970.

In the North Atlantic, accumulated cyclone energy trended upwards in fits and starts from 1968, reaching its highest ever point of 250 in the annus horribilis 2005. But it dropped to 36 in 2013 and was 67 in 2014, levels similar to those seen in the milder hurricane seasons of the 1980s.

How might global warming affect hurricane strengths, frequencies, and storm tracks? In general, model projections suggest that a warmer climate will produce fewer, but stronger hurricanes in the North Atlantic. A 2015 study that analyzed global trends in tropical cyclones between 1984 and 2012 found that rising temperatures correlated with six fewer storms than would have been expected, while boosting average wind speeds by 3 mile per hour. With regard to storm tracks, computer models offer varying forecasts. Some expect fewer hurricanes to strike the eastern United States, whereas others predict that fewer will hit the Gulf Coast while more storms will crash into the northeastern U.S.

Can researchers now discern any effect that the recent increase in global average temperature has had on people and their property? Not really. In the U.S. annual deaths resulting from hurricanes have not exceeded three-digits since Hurricane Agnes in 1972, with the notable sad exception of 1,016 deaths from Hurricane Katrina.

What about economic losses? The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change's 2014 Adaptation report observes: "Economic costs of extreme weather events have increased over the period 1960–2000, with insured losses increasing more rapidly than overall losses." But the report goes on to note that "the greatest contributor to increased cost is rising exposure associated with population growth and growing value of assets." Similarly, the same group's 2014 Synthesis report notes that "increasing exposure of people and economic assets has been the major cause of long-term increases in economic losses from weather-and-climate-related disasters." To repeat: There is more damage because there are more people and more stuff to be harmed.

To see if climate change is adding to the destruction, researchers "normalize" losses by taking into account the number of people and the value of the property exposed to extreme weather events. For example, far more people live in Florida now than 50 years ago, with lots more houses and businesses, so hurricanes that strike there today are more likely to cause damage than those than hit that state, say, in the 1920s. Taking such increases in population and wealth into account, the Adaptation report concludes that "Studies of normalized losses from extreme winds associated with hurricanes in the U.S. and the Caribbean, tornadoes in the U.S. and wind storms in Europe have failed to detect trends consistent with anthropogenic climate change."

A review article published in the January 2011 Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society—surveyed 22 studies of trends in natural hazard losses. The article covered every study that looked at economic losses, covered at least 30 years of data, and was peer reviewed. It found "no trends in the losses, corrected for change (increases) in population and capital at risk that could be attributed to anthropogenic climate change. Therefore, it can be concluded that anthropogenic climate change so far has not had a significant impact on losses from natural disasters."

Another 2010 study actually identifies a "strongly negative trend" in normalized weather disaster damages in developed countries. Translation: In relative terms, the amount of damage caused by severe weather is declining. The authors speculate that this might "indicate a stronger capability of richer nations to fund defensive mitigating measures, which decrease vulnerability to natural disasters over time." Richer societies are likely reducing their weather losses by establishing better early warning systems, enacting stronger building codes, and constructing firmer levees. People may be doing a better job of protecting themselves against the consequences of storms and floods, even though the weather is getting worse.

A 2011 study reporting the results of four different climate models concluded that it might take as long as 40 to 170 years for a clear global warming signal to emerge from hurricane damage data. Basically, projected hurricane damage will be within the bounds of natural causes for some time to come.

So will Joaquin end the current major hurricane drought? It is looking that it will not. Some models suggest it will drop to a category 1 storm as it scoots northward away from U.S. shores. Drought, however, will not be on the minds of East Coasters as they endure the expected onshore inundation from rains associated with the storm this weekend. So fellow East Coasters, batten down and take your hurricane preparedness precautions this weekend.

Show Comments (54)