The Muddied Racial Histories of Our American Presidents

The lengthy history of applying the one-drop rule to our chief executive

If we could only stop thinking about Warren G. Harding's sleazy sex life, writes historian James D. Robenalt in The Washington Post, we'd realize that "[t]his man was a pretty good president." But unfortunately for the 29th president's reputation, Robenalt argues, Harding's coat-closet relationship with Nan Britton and his affair with Carrie Phillips (who blackmailed him) have overwhelmed any appreciation of his achievements: his success in stabilizing the country following World War I, his attempts to address civil rights, his arms-control efforts, and so on.

Worse for Harding's rep, the sex continues to be news: This month, DNA tests finally confirmed Nan Britton's assertion that Harding was the father of her daughter, a claim made quite publicly in her notorious 1928 book, The President's Daughter.

Of course, if we didn't remember the sex, we'd remember Teapot Dome, though Robenalt argues that Harding himself had nothing to do with the infamous scandal. And if it's not the sex or the scandals, there's always the juicy (if discredited) claim that Harding was poisoned by his own wife, a story that hasn't helped Harding's stature, either. Robenalt doesn't bother with the poisoning, but the historian does address the persistent rumors about Harding's race. "[I]f you want to really unbundle Harding's negative reputation," writes Robenalt, "you have to understand that he was charged in the 1920 campaign with having an African-American ancestor."

That's a claim that has never gone away, and has figured prominently in Harding biographies, such as the popular 1968 book, The Shadow of Blooming Grove. ("The "shadow," writes Robenalt, "was the persistent rumor that his family from Blooming Grove, Ohio, had black blood.") That claim has also been the main support for a whole branch of underground, often-amateur historical pamphleteering about presidential racial secrets, the most famous example of which is certainly Joel A. Rogers' 1965 booklet, The Five Negro Presidents.

Rogers (1883-1966) was a black author who wrote a lot of books on race, most of them self-published. A recurring theme in his work is that numerous historical figures who are (or once were) widely perceived to have been of European ancestry were really black, or at least not white, according to one-drop rules of whiteness. Frequently, as when he wrote of people like Alexandre Dumas and Alexander Pushkin, he was right. Other times, as in the case of Cleopatra, he wasn't. Much of his writing is founded on a theory of the "Great Black Men of History"; Rogers believed it refuted the widespread bigotry that assumed racial inferiority.

The full title of his booklet about presidents is The Five Negro Presidents: According to What White People Said They Were, thus announcing up front that he's 1) merely compiling what some white people have said about other (purportedly) white people; 2) not offering any primary sources or documentary evidence in support these claims; and implying that 3) he's not responsible for gossip-mongering among whites.

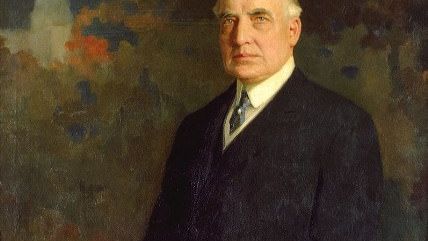

Rogers' cover image is of Warren Harding, inset with a portrait of a black man identified as President Harding's "paternal grand-uncle, Oliver Harding." Rogers' case for Warren Harding's Negritude is drawn from the 1920 campaign material, condensed in a widely-circulated mimeographed sheet, and published full-length as a book entitled Warren G. Harding, President of the United States, by William Estabrook Chancellor, a professor at Wooster College. Chancellor's book featured affidavits from people in Harding's home town of in Marion, Ohio, who swore to have known all their lives that Harding was a member of a black family. One local black journalist is cited as saying that when Harding first ran for office, he himself claimed to be black when speaking to black voters. When Republican leaders demanded that Harding deny the story, he supposedly dodged the question.

That may sound a bit thin, but the other presidential cases are not much more than political name-calling, if that. Rogers' remaining Negro presidents are Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and one mystery president whom he wouldn't name. He provided a give-away clue, however, noting that the unnamed president's mother came from Virginia. That would make the final example Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The charge involving Jefferson relies on an eccentric 19th century work titled The Johnny-cake Papers, in which Jefferson is described as "the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father." That supposedly echoes claims made during Jefferson's lifetime, but no details are offered. Andrew Jackson was identified in a publication called "The Virginia Magazine of History" as the son of a black father; Jackson's own elder brother was supposedly "sold as a slave in Carolina." Jackson's mother, adds Rogers, went to live on "the Crawford farm" following the death of her Irish husband, and there may have met the enslaved man who would be Andrew's father.

"Lincoln was said to be the illegitimate son of a Negro by Nancy Hanks," writes Rogers. Of course, Lincoln was also "said to be" a drunkard and a failed suicide, among many other things, by his livid political enemies. Rogers makes much of Lincoln's dark complexion and wiry hair, and argues that Lincoln was suspiciously reticent about his family; Rogers thinks that he "had a secret preying on his mind." As for Eisenhower, the case for a black Ike seems to rest entirely on this photograph of his mother. Rogers' pamphlet is padded out with similar material about Lincoln's first vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, and Alexander Hamilton, whose West Indian mother was supposedly of mixed racial heritage.

Henry Louis Gates Jr., the country's most prominent black historian, praises the "ambition and imagination" Rogers displayed during his career, especially in such works as his 3-volume Sex and Race. He also credits Rogers with having had "some sort of miscegenation-meter, which he used to 'out' all sorts of 'white' people as having black ancestry. And while he erred on the side of excess as he peered into the proverbial woodpile, Rogers got it right an impressive amount of the time, especially considering when he was publishing his work." But that applies to Rogers' earlier investigations. "At the other end of his collected works, though, stands The Five Negro Presidents, which, shall we say, would get the "Black History Wishful Thinking Prize," hands down, were there such in existence."

Nevertheless, in the years since Rogers' little booklet first appeared, other writers have incorporated its content into their own work and tried to build on it. A writer named Auset BaKhufu, for example, has written Six Black Presidents: Black Blood : White Masks US, adding Calvin Coolidge to the list of black presidents based on his mother's supposed lineage, while Dr. Leroy Vaughn, in his Rogers-inspired book, Black People and Their Place in World History, has also added Coolidge.

By contrast, author Toni Morrison in 1998 shrugged off both Harding and the Rogers School of genealogical suspicion when she wrote in The New Yorker that the country's real first black president was Bill Clinton, based on cultural affinity. "Clinton displays almost every trope of blackness," she wrote, "single-parent household, born poor, working-class, saxophone-playing, McDonald's-and-junk-food-loving boy from Arkansas."

As for Barack Obama, he finally pays off the Rogers School argument in at least one unexpected way: not through his Kenyan father, but through his Kansas-born mother.

The Rogers argument posits seemingly white presidents who wouldn't have passed the racist one-drop rule, and who would have been legally categorized in some states as non-white. All Rogers and his acolytes have lacked in their suppositions of "mixed race" branches on presidential family trees was any actual evidence, as opposed to gossip and name-calling politics.

Enter Stanley Ann Dunham, the president's mom. In 2012, Ancestry.com announced its findings that "President Obama is the 11th great-grandson of John Punch, who was the first documented African to be enslaved for life in the American colonies." Genealogist Joseph Shumway said the president's white mother is a direct descendant of the 17th century figure, through a family whose name came to be Bunch. That family, he said, "continued to intermarry with white people and just became white for all intents and purposes." Shumway added that Ancestry.com was "extremely confident in the conclusion that we've reached."

It's the Rogers School of presidential surprises come to life, except of course that it involves not a white president with a non-white ancestor, but a black president whose white mother isn't as white, by Rogers School standards, as anyone–including the president–had previously believed. Rogers and his imitators had always assumed tangled personal histories, but nothing quite like this.

On the other hand, DNA giveth and DNA taketh away. The same genealogical tests that finally established Warren Harding's paternity of Nan Britton's daughter also established something else: In The New York Times' unequivocal phrasing, "President Harding had no ancestors from sub-Saharan Africa."

Thus, just as the Obama case finally provides an actual case history of presidential one-drop racial surprise, the Harding case, whose superficial plausibility had all along undergirded the whole Rogers School train of supposition, collapses. Maybe that shadow has finally lifted from Blooming Grove.

Show Comments (50)