Listen to Me Marlon

Marlon Brando in his own words.

Listen to Me Marlon is a haunting documentary about a haunted man. British director Stevan Riley was approached by the estate of the late Marlon Brando and given access to more than 200 audio tapes the actor had recorded over the course of his long life (he died in 2004, at the age of 80). Many of these tapes were in the mode of "self hypnosis," made by a man sitting alone in a room. Riley also had the use of a trove of still photos, rare interview footage, and other biographical bounty. Out of these intimate elements he has crafted a film that's not so much about Brando as it is by Brando. There are no talking heads providing outside observations. Only Brando speaks, and he has a lot on his mind.

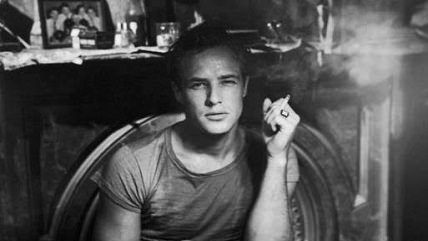

In the movie's non-linear construction, Brando keeps circling back to his childhood in Omaha, and his troubled parents—an abusive father and an alcoholic mother. ("She was the town drunk," he says, almost fondly. "I used to love the smell of liquor on her breath.") Feeling himself unsuited to any workaday career, he made his way to New York to become an actor. The 1947 Broadway production of Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire, in which he played the primal Stanley Kowalski, made him a star. Appearing in the 1951 screen version of the play, he was nominated for an Academy Award. When he actually won an Oscar three years later for his portrayal of dockworker Terry Malloy in Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront, he was surprised—he'd felt his performance was subpar. "You don't always know when you're good," he says here. The audience, he believes, "will create things that are not there…They are doing the acting."

It's a mark of Brando's stature as an artist that the studios for which he worked have been so forthcoming with clips from his greatest films for this low-budget indie. We see him in Julius Caesar (1953) and Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), and later, following a series of box-office flops, in his indelible comeback performance in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972)—a role for which he was forced to audition, but ultimately won another Oscar (which he turned down). Brando was hired again by Coppola for the 1979 Apocalypse Now—but that was a much less happy experience. Brando says here that the director's original script was "stupid, awful," and that he rewrote the whole thing. Coppola denied this, and publicly trumpeted the difficulty of working with Brando, to which the actor responds, "He's a prick. I saved his fucking ass."

Brando is acute in discussing his craft. ("When the camera is close on you, your face becomes the stage.") But he's also frank about the fact that he did some movies solely for money. He says he was paid $14 million for 12 days' work on the 1978 Superman, and allows that another of these paycheck films, the 1968 Candy, was "probably the worst movie I've ever made in my life." But then, he says, "I'm interested in making enough money so that I can say 'fuck you' to money."

Along the way, we learn much about the off-screen Brando, too: His passionate involvement with Martin Luther King, Jr. in the civil rights movement of the 1960s; his championing of the rebellious American Indian Movement; and his near-lifelong love of Tahiti, whose inhabitants, he says, "have the beauty of sleeping children. And when they awaken, they awaken in the nightmare that the white man lives in."

Brando was conflicted about his worldwide fame, about "the illusion of success—to have people staring at you like an animal in a zoo." But he also admits his enjoyment of the many admiring women that fame funneled his way right from the beginning: "I was young, and destined to spread my seed far and wide." (He fathered more than a dozen children.)

In addition to collating his abundance of film and audio material, director Riley also tracked down a 3D digital simulacrum of Brando's head that was made in the 1980s. The occasional use of this spectral artifact is an audacious move, but it works, lending an eerie presence to the words we hear Brando speaking about his many sorrows and triumphs. What has he learned? In the end, he says, "Life is a rehearsal."

Show Comments (9)