There's No Such Thing as Unbiased Journalism, So Stop Pretending

Shock a former political operative was less than honest about his relationship with his former bosses

If you're an intellectually curious person—and if you're a journalist, let's assume that you are—you are likely to have embraced a number of notions about how the world works, how it should work and who should be running it. This is natural. It's inevitable, then, that most journalists have formed some opinions about partisan politics.

It's unrealistic to expect that even the most conscientious journalist can wholly divorce his or her professional work from his or her philosophical positions. And even if that person were to put forth the sincerest effort possible, biases are likely to manifest in the focus and tone of his or her work. And this doesn't even take into account editors and headline writers, often the worst culprits in one-sided political coverage.

So though we have many fine political journalists, we have only a handful of truly unbiased ones in the country.

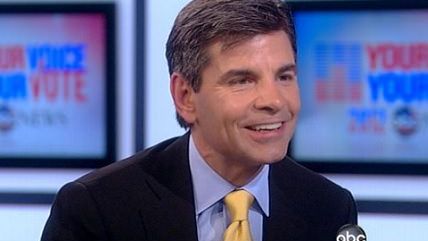

ABC News' George Stephanopoulos is surely not one of them. When The Washington Free Beacon broke the news that This Week and Good Morning America host Stephanopoulos had contributed $50,000 (now $75,000) to the Clinton Foundation, it did not hide its ideological motivations. But bias isn't tantamount to dishonesty. It just speaks to purpose.

Brent Bozell, president of the conservative watchdog group Media Research Center, says Stephanopoulos displayed "an inexcusable lack of journalistic ethics." He's right. Stephanopoulos failed to disclose his contribution before his on-air grilling of Peter Schweizer, author of "Clinton Cash," about the Clinton Foundation's difficulties. Questioning another journalist's work when you're directly involved in a scandal—one you're pretending not to have an opinion on—is in every sense unethical, and not because the former Clinton aide is a partisan. There is little doubt he hid his donation to preserve the pretense of dispassionate coverage. The real scandal is that anyone thought he could provide unbiased coverage even before this revelation.

If Stephanopoulos would have disclosed his charitable giving beforehand, rather than press Schweizer on his past partisanship, he could have asked him: "Listen, I gave money to this foundation, too. I'm a huge fan of the work it does on AIDS and deforestation and working with corrupt Middle Eastern regimes, and I think the entire mission is simply fantastic. What proof do you have that there was a quid pro quo by me or anyone else?"

That would be far more compelling and informative television. Questions are questions, after all. And your outlook doesn't change their legitimacy.

Pointing out bias is fair game, but running from bias is bad form. Bozell also says Republicans should avoid ABC News. After the scandal broke, presidential hopeful Ted Cruz claimed that "debates should not be moderated by partisan Democrats who are actively supporting one of the candidates." And Rand Paul said: "It's impossible to divorce yourself from that, even if you try. I just think it's really, really hard because he's been there, so close to them, that there would be a conflict of interest if he tried to be a moderator of any sort."

This is all true. And so what?

Stephanopoulos is a partisan by the purest definition of the word. He's never been a journalist. He's going to ask Republicans the sorts of questions they should be asked—the sorts of questions they should have answers for. Moreover, no one has to be confused about the questioner's intentions.

CNN's Candy Crowley, on the other hand, is purportedly an unbiased journalist, and she still couldn't help but correct Mitt Romney when he accused President Barack Obama of refusing to refer to the attacks on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, Libya, as a "terrorist act" in a 2012 debate. Well, she didn't exactly "correct" Romney. The Republican, it turned out, had it right. But most of the voters watching, people who don't follow politics as closely as you do, never knew she was mistaken. Her job was to mediate. She interceded. Might as well have openly antagonistic journalists asking questions that matter. In the best of worlds, two antagonist journalists would be asking both candidates questions.

And candidates should have nothing to fear, unless they're insecure in their own beliefs. Whether a communist or an objectivist grilled me about my positions, they would not change. Sometimes your answers can give context or challenge the premise. Paul, for example, responded to a gotcha question on abortion with the sort of feistiness that's often necessary when dealing with adversaries.

When Todd Akin—or whoever the next Todd Akin is—says something stupid, it's because he believes something stupid. Let's not blame the press. When Fox News Sunday host Chris Wallace—one of the few who is equally tenacious with conservatives and liberals—attempted to get an answer out of Marco Rubio about Iraq, he couldn't because the candidate has no good answer.

© Copyright 2015 by Creators Syndicate Inc.

Show Comments (63)