Smoking and Vaping Keep Moving in Opposite Directions Among Teenagers

Where is this "gateway effect" we keep hearing about?

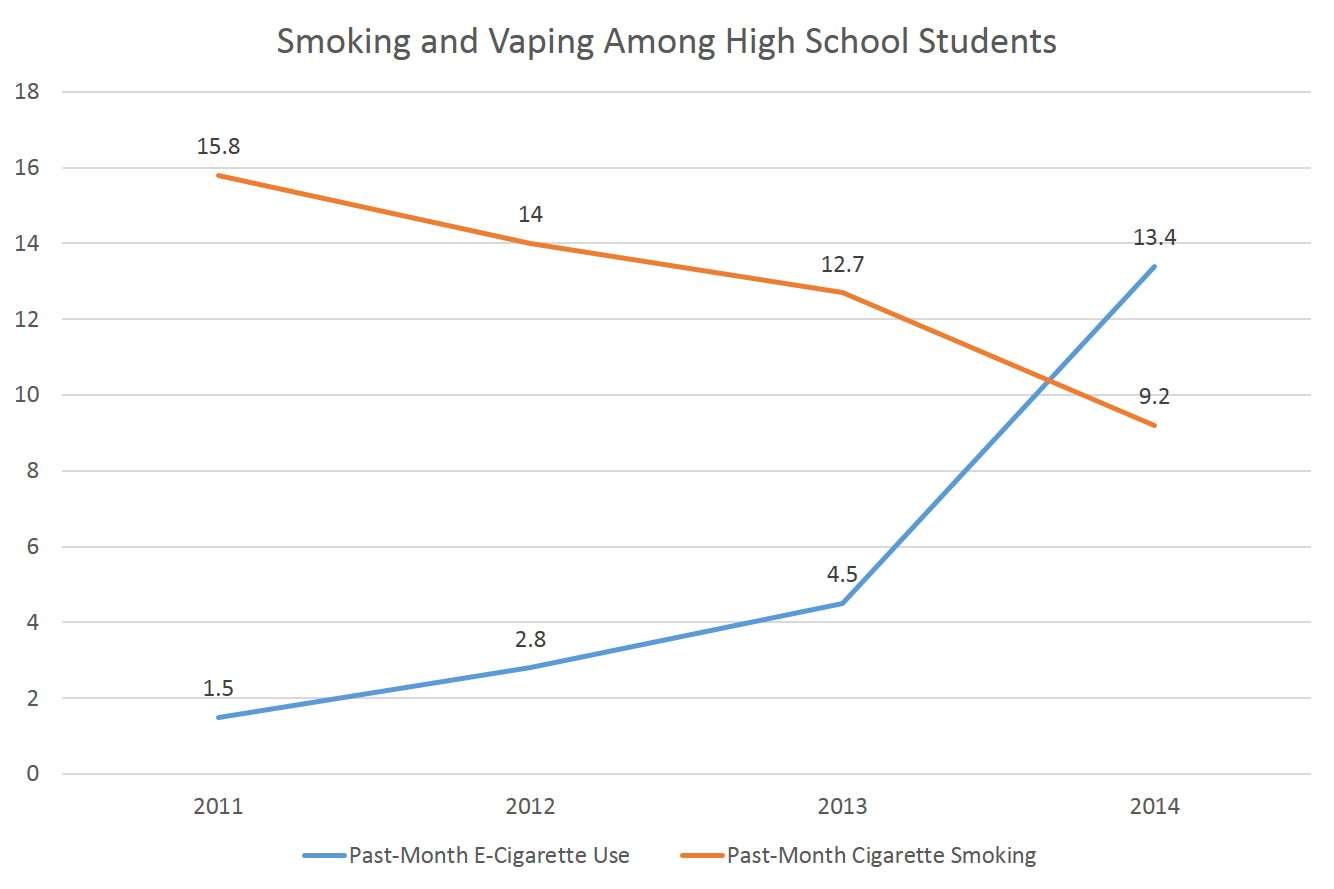

Results from the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey, released today by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, show that smoking continued to decline among teenagers last year even as vaping continued to rise. Needless to say, that is not what you would expect to see if electronic cigarettes were a gateway to the conventional kind, as critics of those products keep claiming. Those critics include the CDC itself, which issued a press release emphasizing that "current e-cigarette use among middle and high school students tripled from 2013 to 2014." The CDC highlights that point in the headline and the first sentence of the press release. In the fourth paragraph, it mentions in passing that "cigarette use declined among high school students and remained unchanged for middle school students."

Among high school students, 9.2 percent reported past-month cigarette use in 2014, down from 12.7 percent in 2013. Among middle school students, 2.5 percent reported past-month cigarette use, down from 2.9 percent in 2013. (The latter drop was not statistically significant, which is why the CDC says the rate "remained unchanged.") Meanwhile, the share of high school students who reported using e-cigarettes in the previous month rose from 4.5 percent in 2013 to 13.4 percent last year; among middle school students, the rate rose from 1.1 percent to 3.9 percent.

Between 2011 and 2014, past-month cigarette use fell from 15.8 percent to 9.2 percent among high school students, while past-month e-cigarette use rose from 1.5 percent to 13.4 percent. The trends were similar for middle school students: Past-month cigarette use fell from 4.3 percent to 2.5 percent, while past-month e-cigarette use rose from 0.6 percent to 3.9 percent.

CDC Director Tom Frieden's spin on these numbers is predictably negative:

We want parents to know that nicotine is dangerous for kids at any age, whether it's an e-cigarette, hookah, cigarette or cigar. Adolescence is a critical time for brain development. Nicotine exposure at a young age may cause lasting harm to brain development, promote addiction, and lead to sustained tobacco use.

Never mind that there is no evidence in the CDC's own survey results to support the notion that vaping leads to smoking. If anything, these data suggest that e-cigarettes are displacing the real thing, which can only be a positive development from a "public health" perspective, give the enormous difference in the risks posed by the two kinds of niciotine delivery systems. The American Lung Association (ALA) suggests that the decline in smoking is "offset by the dramatic increase in use of e-cigarettes," which is scientifically absurd given the clear health advantages of vaping.

Part of the problem is that the CDC and the ALA, like the Food and Drug Administration, count e-cigarettes as "tobacco products," even though they contain no tobacco. These opponents of smoking also seem strangely oblivious to the lack of combustion. Yet these two factors make e-cigarettes dramatically different from smoked tobacco, to the point that it makes no sense to group them together. One might as well call nicotine gum and patches "tobacco products."

A BMJ study published yesterday casts further doubt on the concerns expressed by the CDC and the ALA. Looking at surveys of students in Wales, the researchers conclude that "e-cigarettes are unlikely to make a major direct contribution to adolescent nicotine addiction." E-cigarette use was more common among the Welsh students than conventional cigarette use (which is also true among American teenagers). But only 1.5 percent of 11-to-16-year-olds reported using e-cigarettes at least once a month, and almost all of those regular vapers were also smokers. That pattern suggests that while experimentation with e-cigarettes is increasingly common, regular use remains rare and concentrated among people who already smoke.

Show Comments (113)