An Old New Way To Stop AIDS

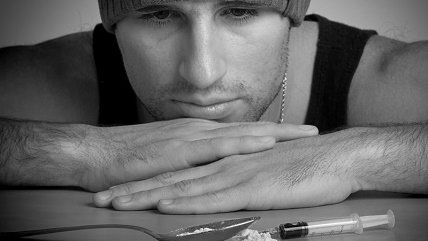

When invited to trade filthy used needles for sterile new ones, drug users often take the safer route.

By signing a religious freedom bill that provoked a hail of criticism, Indiana Gov. Mike Pence did a brilliant job of diverting attention from something deserving of commendation. That same day, he took a wise step to contain an outbreak of HIV infections in southern Scott County.

Since December, more than 80 new cases have been identified in the county. That's up from five in a normal year and the worst epidemic the state has ever seen.

Pence was advised by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that stopping the epidemic would require opening a needle exchange—which would encourage intravenous drug users to turn in used syringes for new ones instead of lending the contaminated equipment to their friends.

The advice could not have been welcome in the governor's office. Indiana law prohibits needle exchanges, a ban Pence still supports. What's more, federal laws forbid the use of federal funds to pay for them—a policy repealed by the Democrat-controlled Congress in 2009 but restored after Republicans gained control in 2011. Pence was part of that GOP House majority.

But last week, taking a brief respite from antagonizing gays and everyone else, he declared an emergency and approved needle exchange in Scott County. The area abounds in people who abuse a prescription opioid painkiller called Opana. Many have been infected with HIV, and when they share syringes with other Opana users, they have a very high probability of spreading the virus.

Drug addicts may not be famously fastidious, but they don't use dirty syringes because they like to. They do it because it's cheaper than buying new ones—which in Indiana also requires signing a register.

But when invited to trade filthy used needles for sterile new ones, we have learned in other places, drug users often take the safer route. Some of them also pursue treatment and other services offered by the programs.

Indiana is not alone in the problem.

Kentucky Gov. Steve Beshear last week signed a bill legalizing needle-exchange programs in response to an epidemic of hepatitis C, a deadly disease that also spreads through the reuse of contaminated syringes. Addressing addicts, he said, "We're coming to help you. Work with us and help us to help you get on the road to recovery."

Part of the motive is fiscal: Treating a patient with this illness can cost the government upward of $1,000 a day. A new syringe costs the government upward of a nickel. There's also something to be said for sparing people from illness and death.

Pence is deferring to harsh necessity, but grudgingly. He authorized the Scott needle exchange for just 30 days, and he has threatened to veto any measure allowing this remedy elsewhere.

The opposition to clean-syringe outreach efforts stems from the fear that they will have all sorts of unsavory side effects, like promoting more drug addiction, fostering crime and leaving more syringes on the street. A wealth of research indicates the fears are unwarranted.

The CDC reports that needle exchanges "do not encourage drug use" or "the recruitment of first-time drug users." Evidence from Baltimore found no increase in the number of arrests after the program began. The very nature of exchanges gives addicts a good reason not to litter the sidewalk with used hypodermics.

What clean-syringe handouts do is encourage more responsible behavior on the part of drug users, which curbs the transmission of HIV and hepatitis C to them, their sexual partners and their children.

A National Institutes of Health committee said, "An impressive body of evidence suggests powerful effects from needle-exchange programs," including "reduction in risk behavior as high as 80 percent, with estimates of a 30 percent or greater reduction of HIV" among injecting drug users.

Some critics bridle at the idea of spending taxpayer dollars to protect drug users from their own behavior. But banning support for needle exchange, notes Bill Piper of the Drug Policy Alliance, doesn't save the federal treasury any money—it just diverts the funds to other prevention projects. Since many of the addicts who contract HIV or hepatitis C end up on Medicaid or Medicare, stinginess on needle exchange is the ultimate false economy.

Three decades after the first experiments in needle exchange were mounted in response to HIV and AIDS, you'd think policymakers everywhere would see their value. In Indiana, they're learning the hard way, but they're learning.

Show Comments (37)